Rory Hopcraft, University of Plymouth; Kevin Jones, University of Plymouth, and Kimberly Tam, University of Plymouth

It’s estimated that 90% of the world’s trade is transported by sea. As consumers, we rarely give much thought to how the things we buy make their way across the planet and into our homes. That is, until an incident like the recent grounding of a huge container ship, the Ever Given, in the Suez Canal exposes the weaknesses in this global system.

Credit ShippingWatch

High winds have been blamed for the container ship blocking the narrow strait, which serves as a trade artery that connects the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. But with shipping so heavily reliant on such narrow channels, the potential for these incidents is ever-present.

As researchers of maritime security, we often simulate incidents like the Ever Given grounding to understand the probable long and short-term consequences. In fact, the recent event is near identical to something we have been discussing for the last month, as it represents an almost worst-case scenario for the Suez Canal and for knock-on effects on global trade.

The Suez Canal is the gateway for the movement of goods between Europe and Asia, and it was responsible for the transit of over 19,000 ships in 2019, equating to nearly 1.25 billion tonnes of cargo. This is thought to represent around 13% of world trade so any blockage is likely to have a significant impact.

The Suez Canal Authority started expanding the strait in 2014 to raise its daily capacity from 49 vessels at present to 97 by 2023. This gives an indication of how many ships are likely to be affected by the current situation. There are reports that the incident has already halted the passage of ten crude tankers carrying 13 million barrels of oil, and that any ships rerouted will have 15 days added to their voyage.

The severity of the incident is because of the dimensions of the vessels using the canal. The Ever Given is 400 metres long, 59 metres at its widest point and 16 metres deep below the waterline. This makes it one of the largest container ships in the world, capable of carrying over 18,000 containers. Depending on the severity of the grounding, the salvage and re-floating of this type of ship is a complex operation, requiring specialist equipment and potentially a lot of time.

While the exact number of container ships of this size transiting the canal is unknown, container vessels account for almost a third of all canal traffic. Their depth and girth make for difficult navigation within the canal. When operating within such tight margins, ships of this size have to maintain a certain speed to keep their steering effective.

With the capacity to carry over 150,000 tonnes of cargo, these ships cannot stop suddenly. If something does go wrong, crews have very little time to react before the ship runs aground.

Mr_Karesuando/Shutterstock

This makes a blockage of this type almost inevitable, especially considering that the length of these ships far exceeds the width of the canal. But what makes this incident particularly disruptive is the location of the grounding. Since the canal was expanded, the Mediterranean end of the Canal now has two channels for ships to take, allowing seamless transiting even if one channel is blocked.

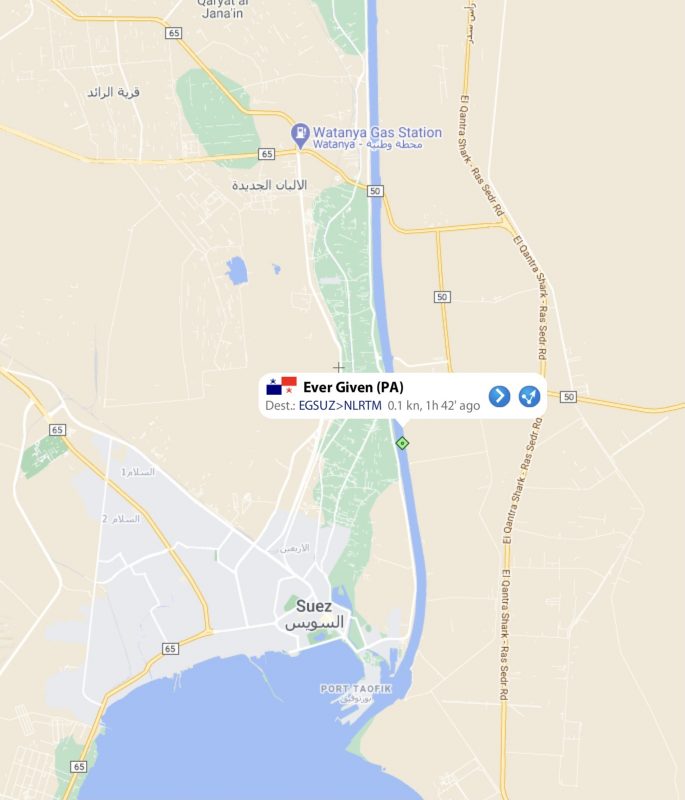

But, in its current location at the Suez end of the Canal, the Ever Given is blocking the only channel for ships to pass through. As ships travel through the 193km of canal in convoys with tightly scheduled slots, vessels leading these groups can block the channel like this, creating a backlog of ships or even collisions. It’s unclear if the goods being delayed are time-sensitive (for example: medicine or food), but understanding what effects these incidents have on trade can help us pre-empt effective solutions.

Could it have been worse?

We’re also interested in what other factors can influence an event like this. One element is the time of year. Traditionally, in the build-up to Christmas, October and November are busy times for maritime trade. A disruption in the global supply chain during this period would have a far greater impact, and could coincide with difficult weather conditions which would exacerbate things, like visibility-reducing fog.

Another element is the unevenness of the canal’s banks. If the incident had occurred only a few kilometres down towards the seaport of Suez where the strait ends, the ship would have run aground on banks composed of rock, not sand. An impact here might have caused serious damage to the hull, making salvage operations harder.

While not identical to our team’s table-top scenario, the latest incident does highlight that as ships get larger and more complicated, their reliance on narrow shipping routes constructed in an earlier age looks increasingly risky. Today’s blockage will have limited long-term implications, but incidents like it could be triggered maliciously, causing targeted or widespread impacts on global and local trade. We need to be more aware of these weaknesses as our world becomes more connected.![]()

Rory Hopcraft, Industrial Researcher, University of Plymouth; Kevin Jones, Executive Dean, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Plymouth, and Kimberly Tam, Lecturer in Cyber Security, University of Plymouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.