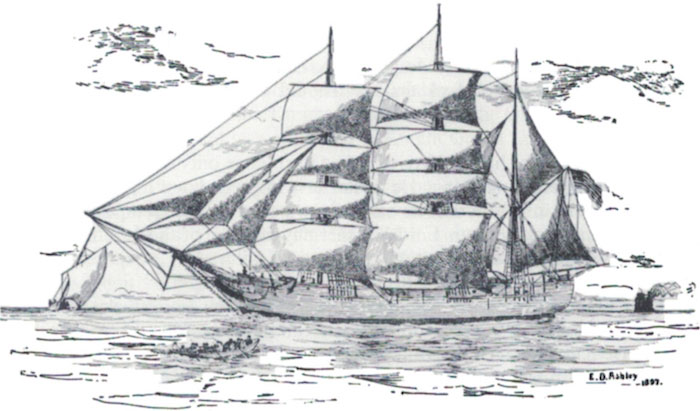

The Fenians were members of a secret, or semi-secret, society dedicated to the end of British rule over Ireland. They recruited, amongst others, Irish soldiers serving in the British Army, even though mutiny was punishable by death. Nevertheless, considerable numbers of soldiers, some estimates go as high as 15 000, some in crack regiments, had taken this risk. The last of the convict transports, the Hougoumont, which arrived in Fremantle in 1868. included, among 280 convicts, 72 Fenians transported for their part in the unsuccessful uprising of 1867. Seventeen of them were former soldiers from the British army, the so-called military Fenians. By 1871, all of the civilian and some of the military Fenians who had been imprisoned in Fremantle had been amnestied and released. Eight former soldiers remained in custody. With the assistance of two Americans who were part of the plot, six of these men were able to escape in the Catalpa on Easter Monday in April 1876. What was the impact of the escape on the warders and other officials? We need firstly to identify these officials.

The Governor of the colony, William Cleaver Robinson, who had been in Perth for around two years, had served as governor of King Edward Island when it united with Canada. There he had witnessed at fairly close quarters an attempted ‘invasion’ of Canada by the Fenians from America. The acting comptroller-general of the Convict Establishment (in effect, Governor of the Fremantle Prison) was William Robert Fauntleroy, who had arrived in the colony with his father in 1852. He joined the convict service in 1854, first as chief clerk to the registrar, then by promotion to chief clerk and to acting comptroller-general.

The assistant superintendent, in effect head warder of the Prison, was Joseph Doonan. Born in Ireland in 1831, he had arrived in Western Australia with his mother and sister in the Travancore in 1853. Joining the convict service in 1853, he had a quick promotion to principal warder in 1859. In 1866, when [he was] seeking promotion, the superintendent acknowledged his ‘sound judgment, industry and high principles’ and described him as ‘the most trustworthy and deserving subordinate officer of this service and as to education, manners and conduct I think him well qualified to take charge of any convict prison or depot. …’ He was appointed assistant superintendent in August 1867 and assumed some of the duties of Superintendent in 1875 on the retirement of the incumbent. The Home Government cut the position as an economy and the duties were divided between Doonan and acting comptroller-general Fauntleroy.

Three other warders were involved. The gatekeeper, Francis Lindsey, (sometimes spelled Lindsay), joined the Prisons Department in Britain as an assistant warder at Chatham Prison, applying for a transfer to Western Australia in March 1867. He arrived in the Norwood, with wife and one child, on 15th July, 1867, and was appointed gatekeeper at Fremantle Prison.

Warders were obliged to wield the lash when corporal punishment was inflicted, but Lindsey found himself unable to carry out this duty in March of the following year, and the superintendent noted that he “… appears to be in a delicate state of health, and to be deficient in the nerve and physique requisite to the effective discharge of the duty of flogger … as gatekeeper he has always discharged these [duties] in a very careful and effective manner, and I consider him one of the most conscientious, and trustworthy officers attached to this prison.” Despite his lack of stomach for the floggers‘ role, when, on 8 February 1871, two prisoners escaped over the wall, Lindsey fired at them, hitting one in the lungs, and was commended for his zeal, energy and promptitude. He was promoted warder in that same year. In 1875, he had been relieved from gatekeeper duties on medical grounds and spent three months on the public works. Unfortunately for him, he was back on the gate on Easter Monday the following year. By 1877, his experiences had hardened him to the point where he was able to bring himself to flog two prisoners.

Assistant Warder Thomas Booler had formerly [been] a private in the Regiment of Sappers and Miners; he had arrived in Albany 1851. After various postings as a warder instructor, he had left the army and returned to England in 1860, joining the Metropolitan Police between 1860 and 1862. After several attempts, he was eventually accepted into the Western Australian convict service, arriving with his family on 14 January 1863. He served in the south west for some years, during which he was reprimanded and fined for refusing to take custody of an absconder from a settler, and for not saluting the Governor. After other postings to country depots, he returned to Fremantle in 1874. There he was the subject of an enquiry to investigate the escape of three prisoners, and was reduced from warder to assistant warder. His appeal direct to the Director of Convict Prisons in London was still pending in April 1876, though Governor Robinson had commented on it that ‘some of his statements would appear to be the product of a morbid imagination and some in their nature must be mere guesses and incapable of proof‘. On 17 April 1876, he was in charge of a party of about 25 men constructing the sea wall near Fremantle’s south harbour.

Last of those most directly concerned was Warder Albert Liddelow, who arrived in the colony in 1860. Recruited into the Convict Establishment in 1865, by 1876 he had had a wide experience, mostly in the bush. He had successfully requested transfer to prison duties in 1874. On the fateful day, he was in charge of two different groups working outside the prison walls, the first cleaning the chimneys in the acting comptroller-general’s residence, and the second group painting his verandah. Among the painters was Fenian Michael Hogan.

The conduct of three other warders. none of them directly involved on 17 April, also came under scrutiny. These were: Principal Warder Thomas Davis; Warder James McMahon; and, Assistant Warder Frederick William Craggs. Davis and McMahon were Irish and Roman Catholic, which might have caused them to have some sympathy for the Fenians. Craggs, a much younger man, was a stonemason and had a large hand in the building of the original Fremantle traffic bridge. His wife, daughter of another pensioner guard, was a nurse at The Knowle, and was later to become matron there. These two were found to have turned a blind eye to exchanges of information which had gone on between the conspirators and prisoners at the prison stables where the two were on duty.

Concerning the warders in general, the following quote comes from a commendatory letter sent by Governor Weld to Fauntleroy when Weld was about to take leave of the colony in 1874. “You have also in some instances had to deal with warders more or less contaminated by long contact and association with the criminal class and not taking so much interest as they ought in their duties, owing to prospective reduction of the service and increased facilities for obtaining other employment in a now prosperous colony.” Earlier in a confidential despatch of 30 March, 1870, he had written that “It is impossible to be confident that the fidelity of prison officers will always be proof against temptation where money is not wanting for the purposes of corruption.”

On Easter Monday 1876, Fauntleroy was absent in Perth, attending a regatta. Of the six soon to make their escape. two, James Wilson and Michael Harrington, were in Warder Booler’s party, working on the sea wall near the new jetty in the south harbour. Another two, Robert Cranston, regarded by Fauntleroy as a ‘model prisoner’, and Thomas Hassett repaired to their place of work in the commissariat stores. Michael Hogan. with two others, was put to work at his trade as painter on the verandah of Fauntleroy’s official residence, notionally under the supervision of Warder Liddelow. Liddelow however was also in charge of a second party of three men who had been sent to clean the comptroller‘s chimneys, with a stern warning from Fauntleroy that the warder should keep a sharp eye on these latter while they were inside his house, as both he and his wife were off to Perth.

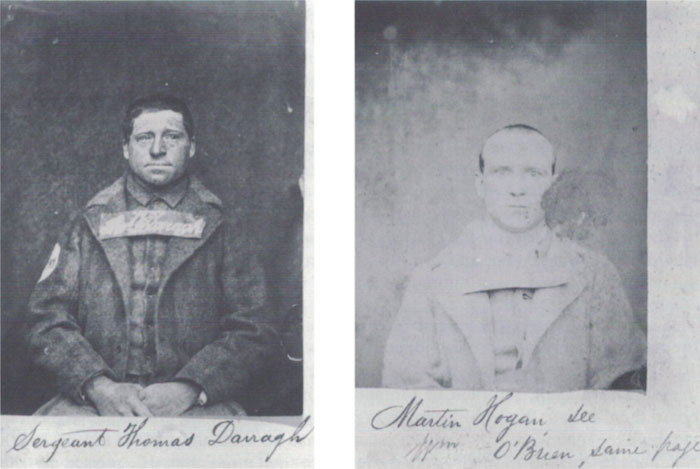

The final Fenian escapee, Thomas Darragh, the Chaplain’s groom and orderly, reported as usual. Gatekeeper Lindsey failed to report that Darragh did not return at his appointed time of 8.15am. He had simply walked off to join the waiting rescuers on the Rockingham road.

At 7.40 am Cranston and Hassett left their place in the stores, closed while the accountant was having his breakfast, and walked out the prison gate. They told Gatekeeper Lindsey that they had been sent to plant potatoes in the garden of Mr Broomhall, the clerk of works, outside the prison walls.

Like these two, Hogan left his painting and, with Hassett, made his way to the Rockingham road. Cranston meantime overtook Booler before he had reached the harbour, and said, “Mr. Booler. I want Wilson and Harrington.” Booler replied that he could not well spare both constables off the works, to which Cranston replied that it was the superintendent‘s order to remove furniture from Government House. Flourishing a key, he said, “Here is the key of the gate.” Under protest, the unfortunate Booler allowed them to go.

All six, with their rescuers, drove off in two horse-drawn vehicles to Rockingham, where they rushed into the Catalpa’s boat for their perilous voyage to the mother ship. At about 9.20 am Liddelow, leaving the chimney-sweepers at work, returned to see how the painters were getting on and found Hogan missing. He was told that he had gone to the lavatory. On checking and discovering that he wasn’t there, he immediately reported to the gate that Hogan had disappeared. At 9.35 am, Gatekeeper Lindsey reported to Superintendent Doonan, in charge in Fauntleroy’s absence in Perth, that Hogan had escaped from the comptroller-general’s quarters, and an immediate report was made to the police. Enquiries soon revealed that the other five Fenians were also missing.

By about 1.00 pm, the escape had been reported to Fauntleroy and the Governor, who immediately made their way to Fremantle, Robinson taking personal charge of the attempts being made to effect a recapture. He arranged with the agent to commandeer the SS Georgette, which was ordered to make ready for sea. The Georgette eventually sailed from Fremantle at 8.45pm. On board were: a twelve-pounder field piece; the Superintendent of Water Police Stone, who, as a magistrate, had been put in charge by the Governor; Major Finnerty, in charge of the Pensioner Guard; seven policemen; and, twenty-two pensioners, with instructions to prevent the absconders’ boat from joining the Catalpa if at all possible.

The attempt at recapture verged on the farcical; the Georgette had to return to Fremantle because at a critical juncture she was running out of coal. However, at 10.00 pm on 17 April, Coxswain Mills, in the Water Police cutter, which had also been out in pursuit, returned to Fremantle, ‘having seen the convicts embark on board the Catalpa, the wind failing him in his endeavour to overhaul the whaleboat in which the men were’. By then the escapees had been 28 hours at sea in very rough weather, 16 men in a small craft designed for no more than 10, missed by the searching Catalpa, and hotly pursued by the water police in their cutter and the Georgette. Their rejoicings were commensurate.

The acting comptroller-general, in the absence of the Governor, who had returned to Perth, ordered the Georgette to sea again. The Governor, in his 18 April despatch to the Colonial Secretary, said that he felt Fauntleroy had acted for the best and should in no way be blamed for having ordered a final search though he was himself quite certain by this time that ‘all further pursuit will be futile.’

The Georgette eventually came up with the Catalpa early morning on 19 April with the distance from nearest land […] judged by Superintendent Stone as about 20 miles. Georgette steamed across the stem of Catalpa, attempting to provoke the Catalpa to fire, thus allowing him to return the fire with propriety. But finally, after an hour, Georgette, daunted by Captain Anthony’s defiant challenge to fire on the Stars and Stripes, gave up the chase.

There were the usual recriminations, and the usual hunt for scapegoats. On 19 August 1876, New York’s Irish World published a letter from Western Australia[:]

I understand that they tried hard to bring some of the unfortunate subordinate officers into a scrape: however I understand that the plan did not succeed and everyone has been acquitted of blame in the matter.

This was not quite the case. Governor Robinson was in a difficult spot. He was at once the judge of the actions of his subordinates, and as head of the administration, having to take responsibility for what had occurred. He faced two special difficulties. He had to justify his actions in the light of a warning he had received from the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Carnarvon, that an escape was to be attempted. He seems from his despatches to have been equally concerned that the Imperial authorities might feel that he should have pursued the chase more vigorously.

It was embarrassing for him to have to report the escape only five days after he had replied to Carnarvon’s warning. He must have regretted writing that ‘the eight [Fenians] who are in prison will be carefully watched by the Comptroller General and I think I may assure Your Lordship that any scheme of the nature referred to which may possibly be set on foot will end in total failure.’

Initially, he blamed Fauntleroy, even though, in view of the security classification of Carnarvon’s warning despatch, Robinson had felt unable to share fully its contents with him. He had, however, had him up to Perth ‘within two hours of receipt of the Personal and Confidential despatch’, for a ‘long consultation’ about the security of the Fenian prisoners. Since then, he said, he had been in constant communication with him, and had been informed ‘from week to week’ that all was well and there had been no appearance of any attempt to hold communication with the prisoners, or of any plot, right up to the previous day. He blamed Fauntleroy for misleading him (perhaps unintentionally) about the state of affairs, but accepted blame for not having asked Fauntleroy to furnish a specific report in writing. He felt that such a course would have been unusual, ‘in dealing with an officer of his position and long experience in the service.’ He had had no reason to doubt that the Comptroller would have acted as they had agreed.

He also sought the Colonial Secretary’s approval of his decision that the Catalpa should not be fired on if it were found outside territorial waters and added he would not have sent the Georgette out a second time when it was known that the Catalpa had already picked up the absconders outside territorial waters. On the second point, the Home authorities agreed. They did not want an international incident with the Americans, and, truth to tell, they were probably rather pleased to have the Fenians off their hands. After the escape, but before the news reached Britain, there had been a debate in the House of Commons on a motion proposing an amnesty for the Fenians. Although Prime Minister Disraeli had dismissed the idea in a cavalier fashion, there was little benefit for any Government in keeping political prisoners incarcerated, even if they were also mutineers.

The tickets-of-leave of the two remaining Fenians were cancelled and elaborate precautions were taken when another American whaler, the Na Malole, appeared on the coast shortly afterwards. There were however, no further attempts at escape. At both the Colonial and Home Offices, Robinson seems to have escaped any blame, getting full marks for his cautious handling of the delicate question of boarding an American flagged vessel on the high seas. He went on to become Governor of South Australia and Victoria, and was returned for two further terms as Governor of Western Australia. In the year following the outbreak he received the traditional reward of the colonial governor, Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George, the KCMG, and was promoted to Knight Grand Cross in 1887.

However, there had to be an enquiry to satisfy propriety, and three worthy members of the Western Australian establishment were commissioned to enquire into and report upon the events. They were: the Hon. A. O’Grady Lefroy, Colonial Treasurer; Mr A.R. Thompson, Assistant Commissary General; and, J.G. Slade, Visiting Magistrate. Their findings, in brief, were that rules of the prison had been departed from in the case of all the absconders but Hogan. Lindsey, the gatekeeper, had permitted Cranston, Hassett and Darragh all to pass out without any special authority, and no special note had been taken of their comings and goings. Booler, who had allowed Wilson and Harrington to leave his gang on the oral request of Cranston, was absolved from ‘any special blame’ on the grounds that the acceptance of oral messages conveyed by prisoner constables was of very general occurrence. Liddelow, who had been in charge of the two parties working at the comptroller- general’s residence was also absolved, as his party was divided ‘and he was left without the possibility of effectually guarding those who composed it.’ The report did not actually mention Fauntleroy’s specific requirement that Liddelow should keep under close supervision those prisoners working inside his house, but that must certainly have been in the minds of the commissioners.

The[y] found that the whole system of appointing prisoners as constables ‘cannot but afford facilities of escape for convicts who are so disposed’, though it had worked well, and without unfortunate consequences, in the past. It appeared to the commissioners that ‘a lax system has gradually obtained in some matters of prison discipline that messages have been transmitted by prisoner constables with far too much freedom, and that too much has been left to the discretion of warders.’ The board made a number of recommendations to improve security including increasing the responsibilities of the gatekeeper to ensure that comings and goings were authorised and better defining the responsibilities of the assistant superintendent and the acting comptroller-general. They recommended that the assistant superintendent should be appointed to the re-established post of superintendent.

Despite Robinson’s initial damning report to the Colonial Secretary, Fauntleroy got off lightly. Blaming the comptroller for failing to take proper precautions after their ‘long consultation’ about the Fenians, Robinson had written in very strong language to Carnarvon:

I now find that instead of keeping a close watch on the Fenian prisoners, and of placing them under the charge of his most tried and trusted warders – the only condition on which I would have consented to their continuing to be attached to the outside working parties – he has actually allowed them to be employed as grooms, gardeners, orderlies, thus removing them altogether from the supervision of the warders and positively facilitating their escape. […] Instead of carrying out my instructions he allowed them to retain their positions, without telling me that he had done so or undeceiving me as to the manner and nature of their employment. It is incomprehensible to me how an officer of Mr. Fauntleroy’s experience can have been guilty of such terrible want of judgment.

This he wrote in the heat of the moment after the escape, and before the enquiry began, and, he says, without wishing to impute blame prematurely to anyone. However, Assistant Superintendent Doonan confirmed in his evidence to the enquiry that the Fenians had received no special treatment to differentiate them from the other prisoners serving life sentences.

Fauntleroy must have felt additional embarrassment since he had personally authorised the tour of the prison by one of the rescuers, and two of the men had been at work on his own residence at the time of the break. This drew unwanted attention to the fact that work was undertaken by prisoners for the benefit of senior prison officials. Doonan being questioned on this subject by the Commission had given evidence that the practice of prisoners being employed in the service of superior officers had been in force since Governor Hampton’s time, and the Comptroller had one such man continuously, and another in his garden.

In attempting to defend himself on the main charges, Fauntleroy had written to the Governor: ‘I confess that I did not believe that men who for years have been employed as trustworthy and reliable constables would abscond at periods when the terms of their probation were drawing to a close.’ An unknown hand at the Colonial Office where the document was referred has underlined the words above, and added an exclamation mark in the margin. Fauntleroy went on that he had not thought an attempt to escape from the public works likely, so took all precautions at the prison itself. This must have seemed as curious a statement to the police of the day as it does now.

In his turn, Fauntleroy was not slow to impute blame prematurely in his first report to the Governor. ‘I consider Assistant Warder Booler gravely to blame in acting contrary to all regulations in allowing any prisoner to detach any men from his party without a regular written order.’ To the enquiry he went even further, saying in evidence that ‘If I had known of an instance of such irregularity I should have dealt with it as a very serious offence.’ The Board thought it a very common one. He also told the Commission that he would not have allowed two lots of men under Liddelow’s control on the morning of the escape if he had known that Liddelow was on his own, and had no prisoner constable with him. In the light of the disappearance of four of these prisoners on that same morning, this statement must have caused some wry amusement.

As well as this, Fauntleroy maintained that until the breakout he was ‘wholly unaware’, and had no means of ascertaining, that there were ‘Fenian agents located in Fremantle with ample means and living at hotels and going about between Champion Bay and the South.’ It is unclear to what precise extent he had been taken into the Governor’s confidence following the receipt of Carnarvon’s warning of a possible escape. Although in a dispatch to Carnarvon after the board reported, Robinson again referred to his consultation with Fauntleroy. Elsewhere he implies that he had not felt at liberty to do more than stress the need for increased vigilance. The Board of Enquiry was not informed of the existence of the confidential despatch, nor of the Governor’s having had his ‘long consultation’ with Fauntleroy following its receipt. Nor did Robinson refer to it even when writing to the Home Secretary, Richard Cross*, in charge of the Prisons Department, who had the responsibility for deciding Fauntleroy’s fate. The Home Secretary nevertheless became aware of it.

Robinson was anxious that the Board’s findings – that Fauntleroy bore no immediate personal responsibility for the escape – might be thought inadequate. Plainly the Home Secretary did think so, irrespective of the precise nature of the warning given him by the Governor.

Cross found the Board’s report as a whole inadequate. The extraordinary facilities which the men seemed to have had for carrying out their plans, and the evidence of Doonan, which pointedly referred the position of each one of the men except Hassett, at the time of the escape, ‘to the verbal orders of the comptroller-general’, did not appear to have been particularly enquired into by the board. But he felt that they raised questions of the greatest gravity in respect of Fauntleroy’s responsibility for the escape.

Approving the Governor’s proposed appointment of a replacement for Doonan as superintendent, Cross requested him to endeavour to carry that arrangement further in such a way as to allow Fauntleroy’s services to be dispensed with. The Governor now seems to have had an access of remorse, and a feeling that he might have been too hard on Fauntleroy. In subsequent exchanges with the Home Secretary. Robinson wrote that Fauntleroy was now so charged with guilt that he could be relied on to carry out his duties with much greater vigilance and activity. He indicated that he would be happy if Fauntleroy were allowed to remain in his present position.

Cross, however, was not to be persuaded, and presently we find the Governor pleading only that Fauntleroy should not be dealt with too harshly when his pension entitlements are decided, and that he should be permitted to remain in office until new arrangements made in conformity with Whitehall requirements for greater economy are in place. Fauntleroy was retired from the post of comptroller in January 1878, and died in France in 1887.

The man who suffered from the affair possibly more even than Fauntleroy was Assistant Superintendent Doonan. Irish himself, he obviously felt that he would be suspected. No strictures were passed on him by the board, indeed they recommended that he should be appointed to the vacant post of superintendent. Nevertheless, he wrote to the Governor on 10 May, before the board had finished its sittings and delivered its report, appealing for protection against an attempt which appears to have been made this day for the purpose of damaging my character… the object … to induce a convict to cast an imputation on my trustworthiness by the zealous manner in which I have always discharged my duty, I have incurred not only the hostility of the prisoners, but also of many of the warders.

Doonan alleged that the evidence he had given against the acting comptroller- general had led to an attempt to get a prisoner to lie that he knew that another prisoner had stolen jewellery in his safekeeping. On 14 June, he was put on one month’s sick leave suffering from ‘alienation of mind’, and two days later, he attempted suicide by cutting his throat, nearly severing the windpipe. Doonan requested leave on half pay until retirement, which was not approved. Instead, Fauntleroy wrote on 5 September informing him that he was to be retired on a pension of £115.18.1 per annum.

A year later, in a memorial [memorandum?] to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Doonan wrote that he had regained his health and was seeking another appointment in Britain or any one of the colonies and that the ill health which led to his retirement was entirely due to the persecution of the Comptroller of Convicts and his friends, and to an apprehension of the grossest foul play used against him by those persons …was daily subjected to every kind of persecution and annoyance until at last from want of sleep was completely driven out of his senses …

The Governor, forwarding the memorial, noted that the comptroller-general accepted full responsibility for the distribution of the Fenian prisoners at the time of the escape, and that he had so advised Doonan the he believed ‘it to be an entire hallucination on [Doonan’s] part to think that Mr. Fauntleroy and his friends have ever desired to persecute him.’ Robinson agreed with Fauntleroy that Doonan had no truer friend than the comptroller, and believed that ‘Doonan’s apprehension of foul play being used against him to be entirely without foundation.’ His state of excitement arose more from his apprehension of neglect of duty being brought against him than any fear, except perhaps a morbid one, of injustice being done to him. Cross decided, not surprisingly, that Doonan could not be reemployed, and that ‘no good object would be attained by reopening the case.‘

Following his misfortunes in 1876, Doonan turned to private enterprise, and entered the drapery and grocery business. By the 1880s he owned a large house in Adelaide St. He died in 1888.

In the reorganisation of the convict establishment that followed the enquiry, Fauntleroy and Doonan were succeeded by that same Superintendent Stone, formerly of the Water Police, who had been in charge of the pursuit on the Georgette. He took over the new office of Superintendent of Convicts, combining the offices of Comptroller and Superintendent, to the satisfaction of the Home Secretary who saw financial savings.

Assistant Warder Booler. as we know, had previously been in trouble with the prison authorities. With an apparent talent for getting the backs up of those in authority, he must have seemed an obvious candidate for scapegoat. Without waiting to hear any plea in extenuation, Fauntleroy had condemned him out of hand for releasing the two prisoner constables on receiving a mere ‘verbal message’ from a third. Doonan too, in his first report on the escape to the comptroller, felt that Booler was guilty of ‘a grave dereliction of duty.’

In evidence to the enquiry, Superintendent Doonan rejected any suggestion that a man might properly be removed from a gang without a written order. He knew of no case of a warder permitting a prisoner to leave his gang on the basis of a mere verbal message.

Booler himself gave evidence that it was in accordance with the rules and customs of the prison to allow constables to be detached without a written order, only a verbal message from a prison offidcer or a prisoner constable being required. He asked that three other warders be called to support this claim. Only one of them did so.

The enquiry nevertheless found that Booler was not culpable, on the grounds that acceptance of oral messages conveyed by prisoner constables was of very general occurrence, and that it had been left very much to the discretion of individual warders whether they should or not accept the authority of an oral message. The board’s finding in Booler’s favour seems against the weight of evidence, and did not satisfy the Home Secretary.

Booler was dismissed in May 1877 and almost immediately left the colony. The Fremantle Herald editorialised on 12 May 1877:

The Board of Enquiry here, we understand, held him blameless but the Home authorities on a perusal of the papers did not concur … his dismissal is considered an extremely severe punishment.

For Francis Lindsey, the gatekeeper, there was, ultimately, a happier outcome. He had been suspended immediately, and then dismissed following the finding of the enquiry that there was no excuse for his dereliction of duty. It could not have helped his cause that Doonan had given evidence that Lindsey had been reprimanded six months previously for a similar offence. The assistant superintendent made the point that the gatekeeper should not have let any prisoner out on his own authority, and should have, but had not, reported that Darragh did not return at the appointed time from his duties with the chaplain. However. Lindsey petitioned the Governor on 22 May on the grounds that he had been dismissed without being given any opportunity to defend himself. A second board was assembled to consider his appeal. Superintendent Doonan and Principal Warder Davis were held responsible for allowing Lindsey to carry the can, their admissions as to the customary practice at the prison gate being extracted with difficulty. Lindsey was reinstated with the approval of the Home Secretary.

The acting comptroller-general wrote to the Governor on 3 July 1876 wondering if Lindsey were to be reinstated whether it would not be better to send him to the Lunatic Asylum.

Lindsey apparently accepted the wisdom of this proposal. It paid off as he received several promotions before he died at Mundijong in January 1910.

Warder Liddelow, as we know, was absolved on the reasonable basis that he could not be in two places at one time. Invalided from the convict service in 1879, he ended up in the grocery business like Doonan, and lived in East Perth until 1919. Principal Warder Thomas Davis had, as we have seen, been categorical that Booler should not have allowed the two men to leave his party on the basis of a verbal message. He was also critical of Gatekeeper Lindsey. He himself, in the event, did not escape unscathed. The Governor‘s second enquiry found that those who had been so harsh in their judgment of Lindsey’s conduct had been disingenuous. Cross now judged that Davis ‘appears to have shown a great want of the qualities necessary for an officer in his position’, and decreed that he should be reduced in rank, ‘unless in course of diminution of staff, his services can be dispensed with.’ Fauntleroy, under threat himself, had to take action on this suggestion, and Davis’ services were indeed dispensed with in July 1877, with his pension reduced to that of a mere warder. Davis appears to have retreated to York, where he is buried.

McMahon and Craggs were also found wanting in their duty by Richard Cross. Their part in allowing the plans for the escape to be hatched behind the stables (which seems to have been revealed by the report of the vigilant detective Sergeant Rowe) must have come to light only after the Governor’s first enquiry, but the Home Secretary felt that that they had connived at the escape in a most culpable manner. There were suspicions at Government House that McMahon was in sympathy with the Fenian movement. He felt the full weight of retribution and was dismissed from service in 1877, while Craggs escaped with a reprimand and a caution to be more vigilant in future.

Home Secretary Cross required a number of changes to tighten up the administration of Fremantle Prison, notably the abolition of the post of Prisoner Constable. He achieved some minor economies at the same time.

Though the police came out of the episode with rather more credit than the warders, certainly in the eyes of Governor Robinson, both services had to put up with a lot of ragging from a public that was on the whole sympathetic towards the escapees. The Fremantle Herald of 22 April reported that [t]he pensioners and police felt that they had been taking part in a very silly farce, and had been laughed at by the Yankees at sea and the public on shore.

A song that was sung, particularly among the Irish, in the pubs and other places around Fremantle and Perth had this chorus:

Come all you screw warders and gaolers,

Remember Perth regatta today.

Take care of the rest of your Fenians,

Or the Yankees will take them away.

It would be easy to see in the findings of the Board of Enquiry a classic case of an establishment cover-up, along with the sacrifice of one or two subordinate officers as scapegoats. In the end though, the system seems to have dealt out even-handed justice. Governor Robinson’s initial fury over Fauntleroy’s conduct having been balanced by the favourable findings of the Board of Enquiry, Home Secretary Cross was left, as was proper, to decide how far it was right to make him carry the burden of responsibility for the escape. One hundred and twenty-five years later, it is difficult to see how the decision could have been other than it was.

* Richard Assheton Cross, later 1st Viscount Cross, 1823-1914, appointed Home Secretary by Disraeli in 1874, social reformer and friend of Queen Victoria.

References

Heseltine, William 2004, ‘The escape of the military Fenians from Fremantle Prison: the warders’ perspective’, Fremantle Studies, 3: 26-45.

Gillard, Garry 2016, ‘Irish Republican Brotherhood, aka Fenians’, [Online]. Available: http://fremantlestuff.info/organisations/fenians.html