Release of the 2021 Australian census data has drawn a flurry of commentary around the sharp rise in those who now tick the box headed ‘No religion’. (For example here are the Fremantle results.) Atheists are rejoicing in what they see as a trend to toss any notion of God out the window. Christians are taking solace from the fact 44% of respondents identify themselves as Christian. Writing in The Australian, Angela Shanahan notes that ‘in sheer numbers Christianity, and Catholicism in particular, is still strong as a percentage of the population’.

Yet, like so many who remain uncomfortable with and unimpressed by this broad data, I think we would get a much better picture of the inner lives of our population if the Census added a couple of simple questions, namely, ‘Do you consider yourself spiritual?’ and, ‘Do you have a spiritual practice?’ True, this might open another can of worms but such questions would provide a welcome outlet for those who are induced to tick the ‘No religion’ box without room for any elucidation of their interior life, and the way their notion of spirituality might translate into some form of regular practice.

It would also add meat to the sandwich if those who nominate a particular religion are invited to disclose whether they actively maintain any mode of observation – such as attending a place of worship, or engaging in prayer or contemplation. A significant number identify, for example, as Anglican – merely because that was the nominal religion of their parents. In other words, they identify as ‘religious’ even though they have not set foot in a church or said a prayer since they were knee-high to a wandering grasshopper.

I find myself wondering what is the real purpose of these questions about faith? Do they help us understand who we are, and what we believe – or are they simply token attempts to categorise our self-perceived religious allegiance or lack of it?

Whatever the case, I reckon there’s scope in our five-yearly census to garner more accurate and meaningful information on how citizens think and feel about their world. Why not ask: ‘In order of importance, list three threats to the future of humanity’? That would get the neurons firing although, in these tiptoe days, it would probably have to come with a health warning.

Some of you may have read an excellent book by the Labor politician, Andrew Leigh, What’s the Worst that Could Happen? Leigh looks at what he calls catastrophic risks such as nuclear war, pandemics, artificial intelligence, and climate change. He examines the pernicious effects of populism – where extreme views are fuelled by fear and anger. Wisdom, he says, is ‘the best antidote to angry populism’ and ‘tackling existential risks is a political problem’.

Books like this – our house seems full of them – can reinforce one’s foreboding about an apocalyptic future, and result in avoidance, denial, or inertia. Or, on the flipside, they can act as a wake-up call, and the motivation to do what one can to reduce the likelihood of a doomsday scenario playing out sooner or later.

Leigh goes on to say the values of ordinary people help determine the course of action taken by governments. I agree. If we treat the Earth as an infinite resource for the human race, placing our demand for ‘progress’ and ‘prosperity’ above that of our land and oceans and atmosphere, plus the wondrous and diverse arrays of flora and fauna that are disappearing before our eyes, we are separating ourselves from the very world that sustains us – the complex, intrinsically-perfected world of Nature. Indigenous communities, in their myths and their stories and their rituals, were attuned to and in tune with this world. Yet we call them primitive and we call ourselves civilised. What irony!

However, this sense of interconnectedness appears incredibly difficult for many people to grasp. Our world is in thrall to a materialistic, consumption-driven, scientific and economic order that goes under the general rubric of global capitalism. Natural resources are treated as never-ending, even though the same science can figure out this ain’t so. The insouciant Australian philosophy of ‘she’ll be right’ seems to have infiltrated all levels of society. Some folk, either through self-interest or self-delusion, propagate a belief that new and better technologies will ultimately solve all our problems. Good luck, I say.

Others, perhaps hankering for Plan B, squander their wealth searching for a habitable planet, just in case beautiful Earth ends up a dystopian basket case, unable to support any form of life.

Optimistic analysts like Stephen Pinker like to point out that, by many measures, modern life is infinitely easier and better than it was for our ancestors. We are healthier, live longer, and have a plethora of conveniences and machines that ameliorate physical drudgery, whether in the home, the field or the factory. We are better educated and have more opportunities – to work, to recreate, to travel, and, in much of the world, to mingle with and shack up with whosoever we fancy. All in all, we are a bloody lucky mob.

No argument. But I think there’s a Pollyanna-ish aspect to Pinker’s writings. And they can obscure the kind of perils that Andrew Leigh outlines so clearly.

So – what hope is there? Are we hard-wired genetically to make a mess of things? I don’t know of anyone who has answered the second question in the affirmative. But the works of one formidable polymath, Iain McGilchrist, have helped my understanding, and make a lot of sense. Far too detailed to describe in this short article, McGilchrist’s thesis is graphically presented in his magnum opus, The Matter with Things, and in an earlier work, The Master and His Emissary. In short, McGilchrist describes how modern thought and culture, individually and collectively, is entrapped within left-brain thinking. The function of this hemisphere is to focus and grasp, and to figure things out in order to exploit, whereas the right-brain takes more of a systemic approach, looking at the whole picture, including context and relationship. Both hemispheres interact and play important and complementary roles – but a grievous imbalance has arisen. Even without exposure to contemporary neuroscience, ancient wisdom traditions implicitly understood these differences. Hence, across cultures there arose stories and concepts around the discrete functions of ‘Master’ and ‘Emissary’. But now, with the advent of scientific materialism and a concurrent devaluing of a more holistic overview, the position has reversed – the Emissary has usurped the Master’s role, unaware that it is ill-suited and inadequate for that position. Give McGilchrist a go – I suspect you will be rewarded. (Readily available online, a number of interviews also introduce the man and his messaging.)

The precious opportunity to live a life on Earth, particularly a privileged life, carries with it, in my mind, an obligation to explore what the heck it is to be human, and our place within the cosmos. It also carries an invitation to make a contribution, no matter how small. Thus, we can attempt to reflect ‘the better angels of our nature’ rather than finding ultimate meaning in things like money, power, or prestige.

Fine words – but, in practical terms, what does this mean?

Each of us has to find our own way. Many people are time-impoverished, busy enough with work and family life. But most of us can incorporate helpful modes of thinking and acting into our daily routines. We just need to be willing, and to take the challenge seriously.

Recently, I was watching a YouTube talk where Paul Hawken, author of Regeneration: Ending the Climate Crisis in One Generation, was talking about groups and organisations involved in climate action and social justice. He decided to make a list, and put it online in the form of rolling credits, like you see at the end of a movie. To cut the story short, the list grew and grew. Initially, it would take a couple of hours for the list to scroll down, then a couple of days, and after that, a whole month!

Hard to believe, yet also incredibly heartening. Around the globe, people, at a grassroots level, are finding time and inclination to contribute something. I felt a breath of hope and encouragement. We can change, and we can support each other, and learn from each other. And in so doing, we can influence our leaders and our fellow citizens. ‘Think globally, act locally’ is more than just a slogan. Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people have taken it on board.

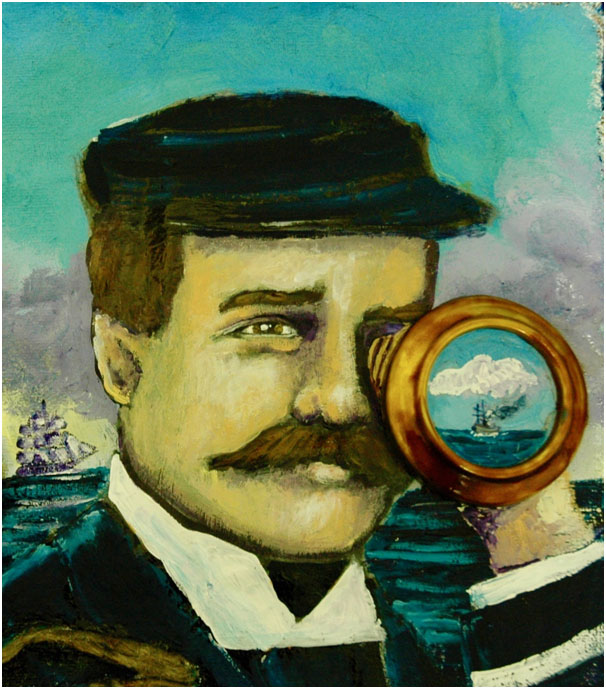

Yet, it would be foolish to ignore the real perils, both present and future. Unlike one of my mates, I could never be called ‘Captain Positive’. There are days when I wallow in maudlin misery, uninspired and touched with a sense of futility. I suspect I’m not alone. Perhaps I imbibed something from my dear, departed mother who would open the West Australian each morning and sigh about how things seem to be going from bad to worse. (What mum would have made of today’s West is another matter, assuming she could get past the Harvey Norman ads.)

Black on Maroon 1959 Mark Rothko 1903-1970 Presented by the artist through the American Federation of Arts 1969 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T01164

I mention this aspect because I know how easy it is to turn away from the horror and anguish we read about in the paper or on social media, and have thrust in our face on television. There are times when we feel like we have to block it out. I can understand this response but I also know that it does not serve me. It’s only if I really accept and feel deeply into the distress of others, and of our Earth, that I can embrace and integrate our interdependence. This recognition gives me the wherewithal to think and act from a place of understanding. Otherwise, I might simply give lip service to wonderful concepts like compassion and equanimity. Otherwise, I could remain frozen in a kind of numbed inertia. Otherwise, I may spend my remaining days making myself more and more comfortable, and ignore what is happening beyond my privileged cocoon.

In this way, the buck does stop with us individually – and it’s clear many people around the world, particularly the young, have taken this as a lifelong commitment. They see the future depends largely on what happens in the present. And, those of them who are moved to look over their shoulders, are informed by examples from the past.

Having once been young, I well know that idealism can morph into cynicism, and commitment can be undermined by a myriad of other priorities and distractions. So I see that those of us who have achieved, simply through the passage of time, a kind of ‘elder status’, bear an additional responsibility to the generations who come after us. We – those of the baby boomer cohort – have benefited from Western affluence, education and freedoms. We owe it to our children and grandchildren – not to become their lecturers, secure in our certainties, but to listen and to gently offer the benefits of our experience. In this way we can hear and be heard, sharing concerns rather than debating rights and responsibilities.

I look with awe and admiration at some energised participants who are a decade or two my senior. Recently, my wife and I watched a series of interviews on the Buddhist website, Tricycle. The amazing Joanna Macy is ninety-three. Her passion is unbounded; her voice, a clarion call for involvement. Long before it was fashionable, she led workshops, introducing her audience to a form of conscious environmental activism grounded in meditation and a quest for self-knowledge. Macy’s spiritual journey, as far as I can tell, is an embodied example where the vicissitudes of ordinary life are embraced rather than pushed aside in the name of individual growth. I resonate with this approach, having learnt the hard way that to separate from society, though it may be necessary and fruitful at one point or another, is not an endgame.

Sometimes we have no clue as to what will induce us to take a fork on the path. If we are moved to give meaning to our lives and curious to explore for ourselves, ideas and those who hold them will appear before us. We may test the water and it may not always be to our liking. We may leave disillusioned or shift our interest elsewhere. But if we truly view our life as a journey to be lived rather than a problem to be solved, I reckon that’s a pretty good start. Listening to Macy, I found myself shaking my head in wonder. While giving full acknowledgement to the state of our planet and human folly, she smiled at the camera and said something along the lines of: ‘I’m really glad to be alive during these times’.

What gratitude is contained in those words! What an invitation to all of us to take them to heart, and give wisdom a chance to incubate and grow.

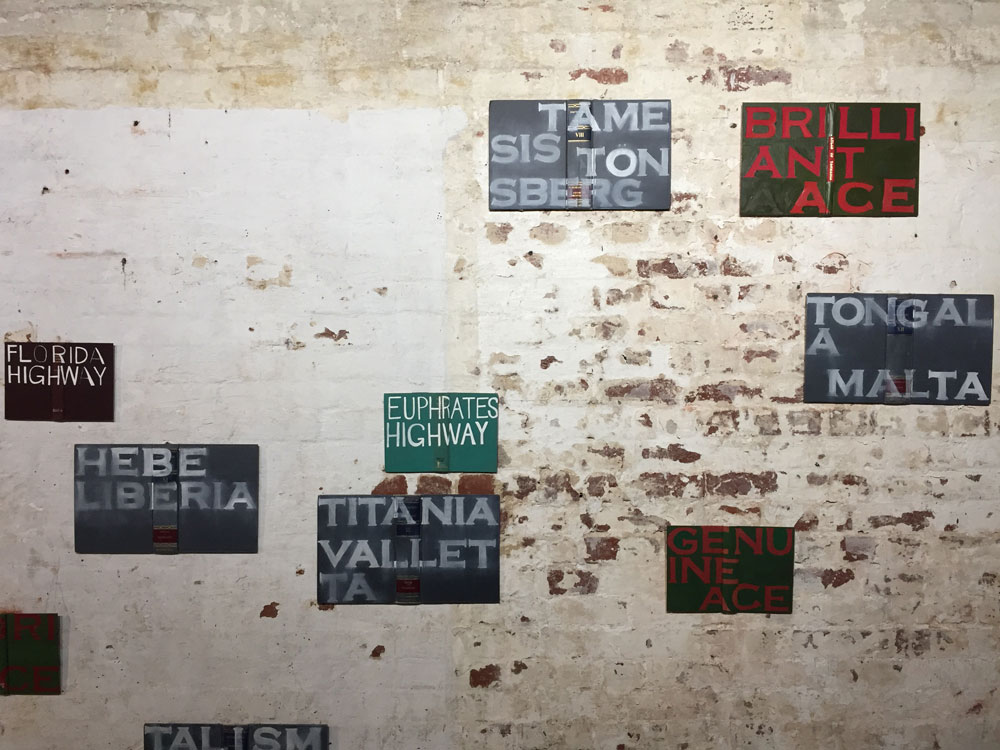

* Based in Fremantle, most of the time, Bruce Menzies is the author of three novels, a family history, and a recent memoir. Details at BruceJamesMenzies.com If you’d like to read more of Bruce Menzies’ work on Fremantle Shipping News or hear a fascinating podcast interview with him, look here!

While you’re here –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!