When you finish reading this wonderfully thoughtful and reflective, and beautifully written, book – mostly biography, like a novel in parts, and small part art history or record of body of work- you re-read the title and come to fully appreciate the ‘of’ Paris part. Not ‘in’ Paris or some other variant, but ‘of’ Paris.

When all is said and done, Kathleen ‘Kate’ O’Connor, an artist who became nationally acclaimed in Australia as a collectable artist of talent towards the end of her long life (she died in 1968 aged 91), was more than reluctant for so long to be identified as an Australian. Born in New Zealand, of a Scottish mother and an Irish father, she at times preferred to be associated with the country of her birth than that to which she moved as a 15 year old in 1891 with her mother, Susan, her siblings and her soon to be famous engineer father, CY O’Connor, the maker of Fremantle’s inner harbour and the Mundaring to Kalgoorlie pipeline.

Given her druthers, and if money had not been an object, Kate surely would have lived her whole life in Paris from the time she arrived there, in 1907, at around the age of 30. Even when the Germans were advancing on Paris in 1940, she was slow to leave. As one of those pretty much on the last train out to the coast, bound for London, she was lucky to make it: her train was bombed along the way.

While Kate O’Connor’s life and work has been written about in the past by Hutchings, and Gooding, to different ends, in Kathleen O’Connor Of Paris, published by Fremantle Press, Amanda Curtin paints a tender and engrossing account of a turn-of-the-century (19th to 20th, that is) woman who embraced a bohemian lifestyle, although the word ‘bohemian’ is perhaps not used today in the same way it was back then. She was, and wanted to be different from the ‘average’ young lady of her era. ‘Settling down’ into a career, or marriage and motherhood was not on her mind.

Kate O’Connor was determined from the start, as a young woman in Wellington, it seems, to be an artist. She continued to pursue her dreams in Perth. And she kept on dreaming. As we read her story, especially from Paris on, we may reasonably wonder whether, if she weren’t from a socially significant and financially comfortable background, with siblings who seem always to have been supportive of her, Kate could have engaged with her dreams so wholeheartedly and for so long. But something in her demeanour and never-say-die attitude to life tells us that, in her case, nothing would have stopped her. She was determined to live her life on her own terms. Curtin invents a word for her – ‘Bravegirl’.

Curtin, a novelist who has here turned her hand to something different, takes on the task of providing us with more than an appraisal of O’Connor’s place in the world of art, and avoids writing, as one might have, an imagined life – a ‘faction’ or even a novel inspired by her subject. Instead she gives us a faithful account, with all relevant biographical details and sequences of and in Kate’s life from her birth to her death, and desperately seeks answers to questions about what inspired Kate at each step along the way; about exactly who she was and what was she thinking. Curtin keeps coming back to the facts and the evidence that might support reasonable inferences as to the hows and whys of O’Connor’s life. She refuses to speculate. She does, though, provide enough raw material to allow us, the readers, to do so.

To these ends, Curtin assembles an enormous data base of relevant information about the life and times of Kate. She travels to the places in Paris and beyond where Kate lived to set the contemporary context in which Kate lived her life. She recreates the circumstances of Kate’s living quarters in Paris – not flash. She researches the cost of living in Paris at different times – cheap early on but expensive later. She explores what impact Kate had, as an artist, on France – not great. She descends into the personal and asks about Kate’s love life – and does her best to answer the question.

The whole thing is entrancing. The life led by a woman, not from Paris, in Paris, during the first half of the 20th century. Curtin conveys a sense of the times, in Paris, and in Perth – which is interspersed in the story – both before the Great War, between the wars, and after the second war, especially in the art world. The two could not have been more different. But fortunately for Kate, and indeed for many local Western Australian artists, Perth had at least one great art patron back then,Sir Claude Hotchin.

Kate plainly had little interest in living in Perth, but her supportive siblings and their families did. And so did Hotchin. Ultimately, late in her life, Kate – who had been up until then a European from the Antipodes who had learnt to paint in an impressionist way, and had no real time for the Antipodes – returned to Perth to live out her life as an artist. And she stuck to her life’s mission to the end.

Quite a remarkable person. As you read this book, you are drawn into a time of possibility in the Western world where all roads seemed to lead to Paris, especially for the creative. It was in the period before the second war, when Paris was what New York became after the second war. And Kate O’Connor loved it.

I suspect we all have, or would like to have, an Aunt Kate or a Great Aunt Kate in our lives or in our family tree, to encourage us to take, at least occasionally, the path less taken. To throw caution to the wind. Once in a while to shock. In 70s parlance, to be Easy Riders, if not Thelma and Louise. As we read Amanda Curtin’s account of one woman’s zest for an artistic life we find ourselves barracking for her, hoping she won’t falter, and will indeed succeed.

In the end, Kate provided in her will for her ashes to be cast into the sea off Fremantle. One imagines her thinking was various. Somewhere near her father, who took his life nearby nearly 65 years earlier. Not wanting to be laid to rest on Australian soil, to which she was never fully attached. And, one suspects, hoping that, like a message in a bottle bobbing along on the high seas, she might find her way back, somehow, for one last time, to Paris.

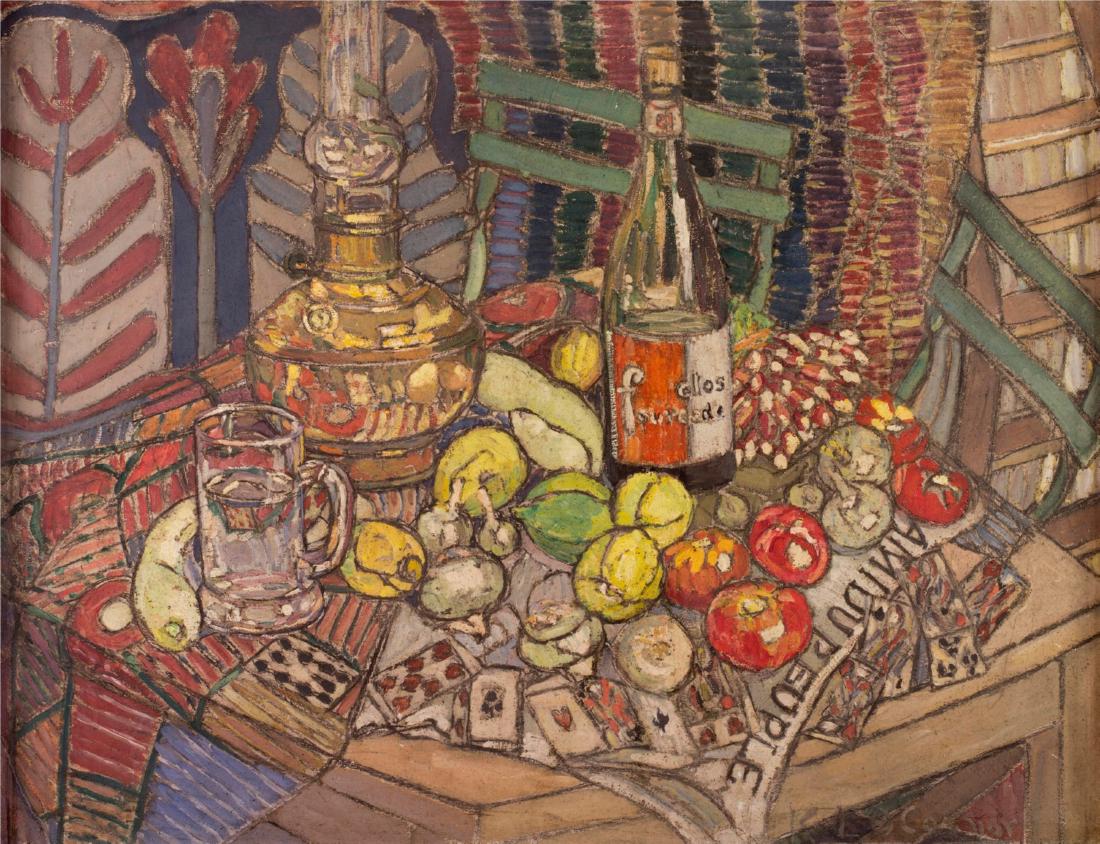

A good biography, like a good novel, is always challenging, enticing, informing and enriching the reader. It tells us truths about the world around us, about others, but mostly about ourselves. It makes us sit back, when we have finished reading, and reflect on how complex, and how wonderful, life can be, and how fascinating we humans are at best. This book, on all those scales, does not disappoint. It also makes you want to return to Kate O’Connor’s paintings soon and look at them afresh.