The duelling sides in today’s cultural wars about “Western civilization” are united in one thing, at least – each is inclined to gloss over the extent to which “Western civilisation” has always been deeply complex and divided.

The fact that leading conservatives like Edmund Burke or Joseph de Maistre, as well as revolutionaries like Karl Marx or Rosa Luxembourg, all belong to “Western civilization” ought by itself to give the protagonists pause.

But take the 18th century enlightenment, for example, since it is a period of Western history central to these debates. In ways that might have surprised Voltaire and his friends, today the Right is laying claim to “the enlightenment”, for its advocacy of freedoms of speech and religion, and as a distinguishing marker of “the West”, against the rest. Parts of the Left want to denounce “the enlightenment”, for its supposed naive faith in reason and support for European imperialism.

So, does the thought and writing of this extraordinary cultural period actually fit either mould?

Read more:

ANU stood up for academic freedom in rejecting Western Civilisation degree

Well, consider a now-little-known work first published in Paris in 1770, entitled The Philosophical and Political History of the Establishments and Commerce of Europeans in the Two Indies (or History of Two Indies for short).

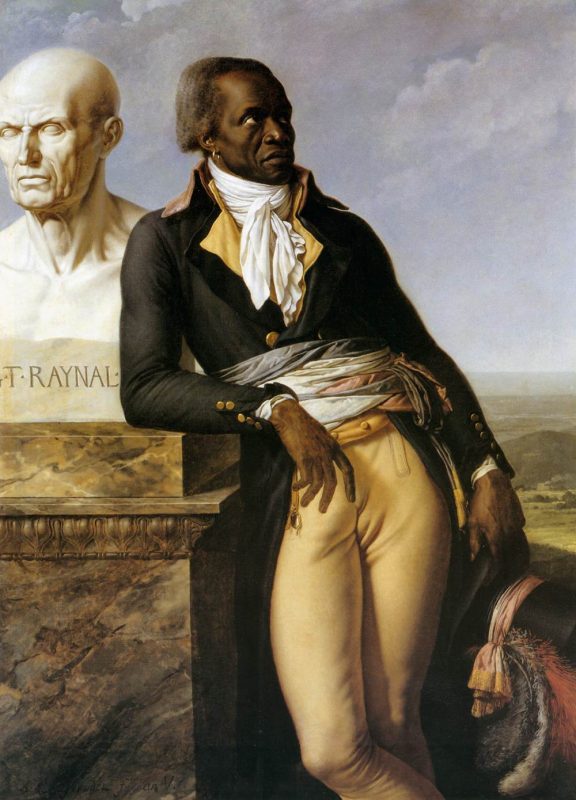

Commissioned and coauthored by an Abbé, Guillaume-Thomas de Raynal, with notable help from leading enlightenment philosophes, the book was central to the enlightenment on any reckoning. In the decades after it was released, it was reprinted some 30 times in France and North America.

Despite everything we might expect today, the book represents one of history’s most forthright attacks on European colonisation, inspiring François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture, leader of the 1791-1804 Haitian revolt which overthrew French colonial rule.

Jean-Baptiste Belley, Deputy of Saint-Domingue and French National Convention member (1793-97) with a bust of Abbé Raynal.

“Among enlightenment publications none … had a greater effect on both sides of the Atlantic and the rest of the world,” writes leading scholar, Jonathan Israel.

In a famous passage, written by Denis Diderot, the History of Two Indies calls for a

“Black Spartacus” to cast out the colonisers:

Where is he, this great man that nature owes its offended, oppressed and tormented children? … There is no doubt that he will appear, he will show himself, and he will raise the sacred flag of liberty … The Spaniards, the Portuguese, the English, the French, the Dutch, all their tyrants will fall prey to arms and flames … The old world will join the new world in applause. The name of the hero who will have re-established human rights will be blessed and memorials glorifying him will be erected everywhere.

After Diderot finished ghostwriting its 1780 edition, History of the Two Indies is unflinching in its attacks on the slave trade, and the greed, arrogance and violence colonisation has unleashed:

Settlements have been formed and subverted; ruins have been heaped on ruins; countries that were well peopled have become deserted… It seems as if from one region to another prosperity has been pursued by an evil genius that speaks our several languages, and which diffuses the same disasters in all parts.

There are laws of fair dealing that apply to all peoples, irrespective of colour or creed, The History of Two Indies argues. If a territory is unoccupied, it may be occupied. If it is partly occupied, the unoccupied parts may be peaceably occupied, with the consent of the previous inhabitants. If the territory is occupied, the newcomer must ask and submit to the hospitality of the hosts, who can also refuse it.

Read more:

‘Western civilisation’? History teaching has moved on, and so should those who champion it

Beyond this, there is an inalienable right to resistance, grounded in a common human nature. In the remarkable words of the Tahitian elder in Diderot’s 1772 Supplement to Bougainville’s Voyage:

We are a free people; and now you have planted in our country the title deeds of our future slavery. You are neither god nor demon. Who are you then to make slaves? … ‘This country is ours.’ This country is yours? And why? Because you have set foot there? If a Tahitian landed one day on your shores, and scratched on one of your rocks or on the bark of one of your trees, ‘This country belongs to the people of Tahiti,’ what would you think? … the Tahitian you want to seize like a wild animal is your brother. You are both children of nature. What right do you have over him that he does not have over you?

It is such moral reciprocity, blind to race or religion, that underlines the History of the Two Indies’ opposition to colonisation, and denunciation of European actions, nearly 200 years before the advent of post-colonialism and post-modernism.

“O Barbaric Europeans!” Diderot writes:

I have not been dazzled by the splendour of your deeds. Their success has not obscured their injustice … if I cease for one moment to see you as so many flocks of cruel and ravenous vultures, with as little morality and conscience as those birds of prey, may this work and my memory … become objects of the utmost contempt and execration.

As Sankar Muthu has commented, for the enlightenment philosophes, Western civilisation was not yet “fit for export”.

Read more:

The concept of ‘western civilisation’ is past its use-by date in university humanities departments

But today, The History of Two Indies is hardly remembered at all — even as New Rights and Lefts debate opposing visions of Western civilisation, and throw around competing visions of “the enlightenment” that equally pass over Raynal’s work.

Perhaps history serves us better when it is able to contest, not confirm our certainties. And that is one, unsettling message that the critical study of any lasting civilisation teaches us.

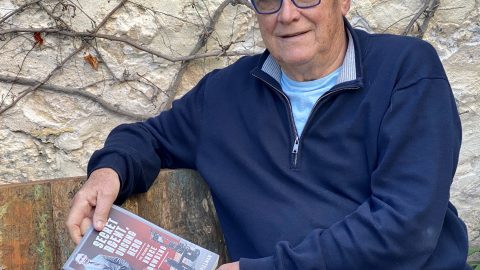

Written by Matthew Sharpe, Associate Professor in Philosophy, Deakin University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()