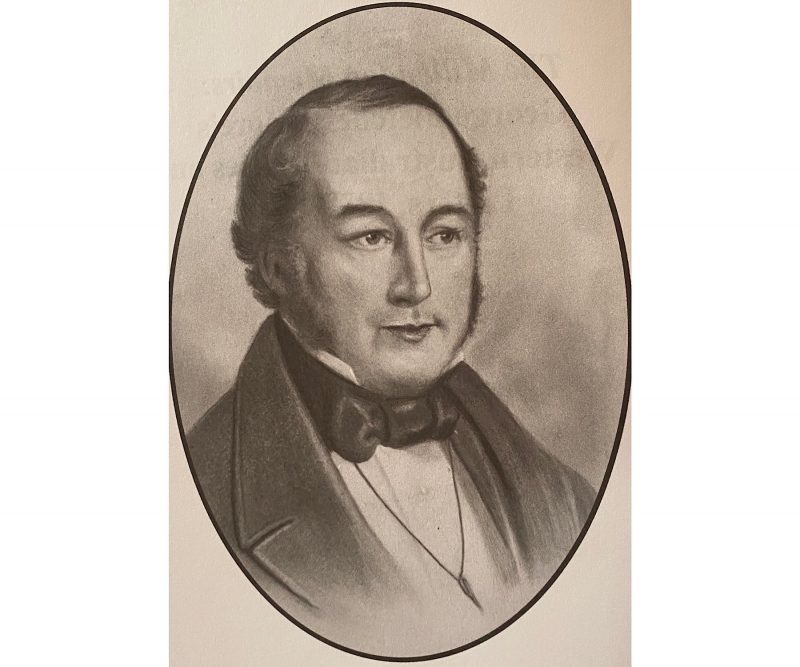

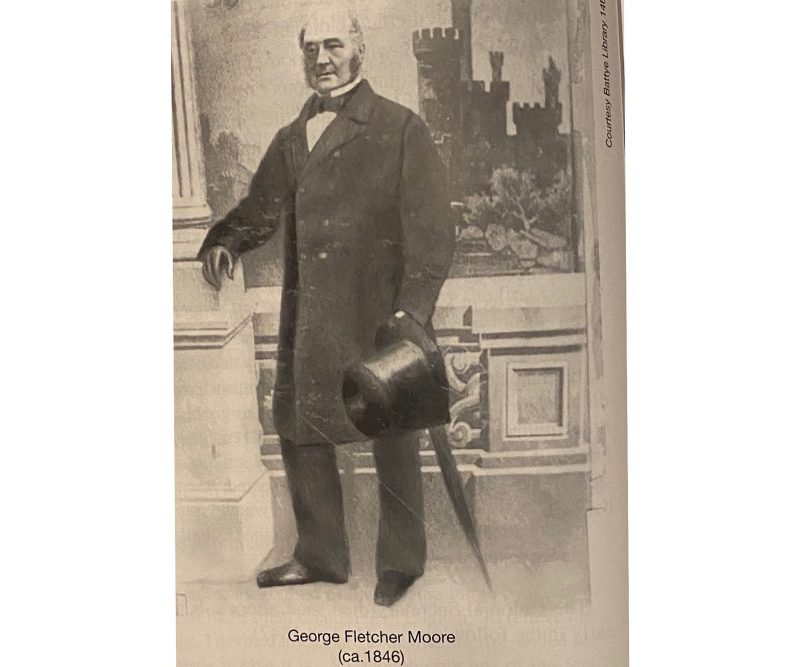

On Friday, 29 October 1830, George Fletcher Moore, a soon-to-turn 32 year-old lawyer from Derry in the north-west of Ireland, arrived in the barely year-old Swan River Colony, full of hope and ambition.

George Fletcher Moore, ca 1841, Battye Library

He spent his first few nights, with his four servants, on Garden Island, just off Fremantle. By Sunday he had found his way onto the beach at the ‘embryo town’ of Fremantle. From there he boarded a small boat belonging to Mr Peter Broun, the Governor James Stirling RN’s colonial secretary, and found his way up the river the British called the Swan, after the name the Dutch Captain Vlamingh had given it in 1697.

Before he knew it, Moore found himself even further up the river – that the local Noongar People called the Derbarl Yerrigan – tagging along with a party of soldiers led by the same Peter Broun who had been tasked to investigate a report that ‘natives’ had been ‘spearing cattle’ and engaging in ‘general hostility’ at the head of the river.

As it happens, the party caught the natives in the upper Swan in the act of ‘plundering a house and enjoying the spoil’. In modern day police lingo, it was a case of ‘break and enter’.

In his journal entry made a few days later, on 12 November 1830, Moore recorded the sequence of events just outlined, and proceeded to describe what then happened to the natives –

‘One was shot dead, several were wounded and seven were brought prisoners to Perth. One of these seven was wounded. He was treated with kindness and kept in hospital till he recovered when he was dismissed as were all the rest and it is hoped that the lesson which was taught them, the superiority which they must have perceived in weapons and strength the cooperation and the subsequent kind treatment may prevent any further annoyances.’

This, it seems, was the way things like breaking and entering were officially dealt with from the get-go in the infant colony. But none of this should have come as a surprise to Moore, if indeed he were surprised. It was in fact the way the British had been engaging with Indigenous peoples throughout their Empire – in North America and elsewhere – for a long time, as Moore, soon enough, came to fully reflect upon.

By July 1833 – just two and a half years after his arrival and a year before he was appointed, by Governor Stirling, as Civil Commissioner and later as Advocate General of the Colony between 1834 and 1846 – Moore found himself sufficiently disillusioned with the way the Aboriginal people of the new Colony were being treated that he wrote a series of letters to the newspaper of those early years, the Perth Gazette. Writing under the pseudonym ‘Philaleth’ – an abbreviation of Philalethes, the ‘truth teller’ of Greek mythology – Moore suggested it was time to ‘conciliate’ and compensate the natives for being ‘dispossessed’ of their country and having to suffer the impacts on their culture and lives that British settlement had wreaked upon them.

Moore’s 1833 letters anticipated both the 1992 decision of the High Court of Australia in Mabo nearly 160 years later, and the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart calling for A Voice, Treaty, and Truth some 185 years later.

In his first letter published in the Perth Gazette on 13 July 1833, Moore did not hold back. First, he referred to what a ‘learned commentator on the laws of England’ had written in analyzing the title by which individuals claim exclusive possession to land under English law, namely, that it was a title ‘derived from the natural right arising from prior occupancy’.

Then he cited what the same learned commentator had written about the recognition of native title under English law –

“Upon the same principle [of prior occupancy] was founded the rights of migration, or sending colonies to find out new habitations, when the mother country was overcharged with inhabitants; which was practised as well, by the Phoenicians and Greeks, as the Germans, Scythians and other northern people. And, so long as it was confined to the stocking and cultivation of desert uninhabited countries, it kept strictly within the limits of the law of nature. But how far the seizing of countries already peopled, and driving out or massacring the innocent and defenceless natives, merely because they differed from their invaders in language, in religion, in customs, in government, or in colour; how far such a conduct was consonant to nature, to reason, or christianity, deserved well to be considered by those, who have rendered their names immortal by thus civilising mankind.”

Highlighting British colonial law and policy elsewhere in the world, especially in North America, in failing to treat native peoples equitably and justly, and advocating for a better approach in Western Australia, Moore concluded this first letter to his fellow settlers, including the Governor, with this plea –

“Believing, as I do that the views of our present local Government, are decidedly friendly to the natives, both upon principle and from motives of sound policy, I trust I am not too sanguine in expressing a hope that the day is not far distant, when they shall be enabled to carry into operation, matured plans of effectual conciliation; and that whilst on the one hand, the condition of the Aborigines may be ameliorated, on the other, our lives and property may be secure from hazard,—so that their procurement of subsistence may be compatible with our enjoyment of the soil.”

Moore’s second letter was published in the Perth Gazette on 27 July 1833. In what was becoming his trademark, forthright, truth-telling style, ‘Philaleth’ stated his case bluntly –

“Let us look now to that act in which we are all parties concerned; namely, the Settlement of Swan River,—and here though every praise is due to Governor Stirling for his prompt endeavours to guard the persons of the natives from wanton outrage, by a Proclamation nearly contemporaneous with the very foundation of the Colony; yet does it not strike us all with surprise that such a state of things should have come upon us unawares, that we should have plunged into such a situation without consideration—without forethought. How few of us deigned to bestow even a thought upon the existence of a people whom we were about to dispossess of their country. Which of us can say that he made a rational calculation of the rights of the owners of the soil, of the contemplated violation of those rights, of the probable consequences of that violation, or of our justification of such an act? If perchance at any moment the murmurings of our conscience made themselves heard, were not its faint whisperings strifled by the bustle of business, or drowned in the din of preparations? Did we not swim the stream in a state of high wrought excitement, from the novelty of our sensation and the rapidity of our course, without reflecting that this rapidity might be an indication of the vicinity of an awful cataract, towards which we were hurrying in a heedless and blind security? Did it never occur to us then, that in thus extending the dominion of Great Britain, in thus acquiring a territory for our country whilst seeking a fortune for ourselves, we were about to perpetrate a monstrous piece of injustice, that we were about to dispossess unceremoniously the rightful owners of the soil.”

Moore then proceeded to address his own observations, asking what was their ‘scope’. ‘Not surely for the purpose of making an idle clamour about that which has been done and cannot be undone’, he said. Nor ‘to make a useless parade of our injustice.’ But –

’…solely with the object of impressing upon the minds of every individual among us, that we owe the Aboriginal Inhabitants of this country a debt which as honest conscientious men we are bound to discharge, and that, not by forbearance alone for petty thefts and trifling injuries, as far as our nature will permit; but by acts of substantial good—by advantages equivalent to those of which we have deprived them.’

Moore suggested it was the ‘business of the Government’, rather than the settlers, to take the necessary conciliatory action.

In his third letter, published in the Perth Gazette on 10 August 1833, Moore extolled the example of the settlement of the tribe of the ‘Mississaguas’ in Upper Canada, quoting from an impeccable source, Captain Hall. In short, Hall’s account explained that following the near extinction of the tribe from the impacts of British colonisation, with the steadfast assistance of missionaries, the indigenous people had reversed their fortunes.

Moore considered ‘every sentence of [Hall’s] account’ was ‘pregnant with instruction and encouragement to us’ to emulate the Canadian example. However, he recognised that, thus far, a policy of ‘conciliating the natives’ in Western Australia had been considered on the grounds of justice and equity alone, an approach he recognised did not meet with universal settler approval. He noted –

‘I am aware that this view of the case, is liable to be, nay in some instances has been encountered with sneers, and assailed by ridicule. These may be found by such as indulge in their use, serviceable as narcotics to lull their consciences into apathetic insensibility; they will not be found to be specifics to heal the disease. But Sir there is another consideration which affects every individual no matter how callous in other respects ; an argument that comes home to all – that is self interest…It is in every respect the interest of the settlers to be on terms of friendship with the natives.’

As we know from our post-1829 Western Australian history, despite the strongly expressed views of Moore then, and those of like-minded settlers and their successors expressed over the ensuing decades, conciliation was never truly considered, and Indigenous peoples continued to be marginalised in the new and expanding Colony.

Indeed, hardly had a year had passed after the publication of the third of Moore’s three letters in the Perth Gazette, when on Tuesday, 28 October 1834, Stirling himself led a party comprising some 25 soldiers, police and settlers that engaged members of the ‘Murray River Tribe’ near modern day Pinjarra, just south of Perth. In his journal entry for Thursday, 30 October 1834, Moore noted the ‘strange rumour’ of the ‘encounter’, as the Perth Gazette described it on 1 November 1834, that 35 natives had been killed. Moore met with Governor Stirling the very next day, Friday, 31 October 1834 and received the Governor’s first-hand account of what occurred. Historical accounts as to how things unfolded, and how many and who died, differ in detail, but by Stirling’s own account to London dated Saturday, 1 November 1834, at least 15 Aboriginal men were killed – and one member of his party. Moore noted in his journal account of his meeting with Stirling that: ‘The women and children were protected, and it is consolatory to know that none suffered but the daring fighting men of the very tribe that had been so hostile’.

Moore then signed off on this entry by noting:

‘The destruction of European lives and property committed by that tribe was such that they considered themselves quite our masters and had become so emboldened that either that part of the settlement must have been abandoned or a severe example made of them. It was a painful but urgent necessity, and likely to be the most humane policy in the end.’

Plainly, the settlement was not about to be abandoned near Pinjarra. Moore, who just the year earlier had been advocating for conciliation with the traditional owners of the new Colony, can now be seen as something of an apologist for the sort of colonial conduct he had previously deplored. At the least he appears to have been conflicted by such events.

By the end of 1834, notwithstanding Moore’s personal views, the pattern of local WA Government policy towards the Indigenous peoples of Western Australia had been well set for the period of colonial expansion ahead. Conciliation was not a tool to be found in the official toolkit.

Moore himself became a major landowner and participant in colonial life in Western Australia until he left the Colony in 1852, not to return, and died in London in 1886.

Under growing colonial law and policy, Indigenous peoples were barely recognised except in measures designed to control their very existence. The idea that they held native title over their traditional country or might be accorded a say in the making of the laws and policies impacting their lives was simply unthinkable, and met with the sneers and ridicule Moore had experienced when advocating the policy of conciliation to his fellow settlers and the local Government.

With Federation and the coming into operation of the new Australian Constitution from 1 January 1901, Indigenous peoples remained as invisible to officialdom within the new Commonwealth as ever. The new Constitution did not recognise them, except in provisions avoiding engagement with them.

Section 127 of the new Constitution provided that ‘In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, aboriginal natives shall not be counted.’

And while section 51(26) gave the Commonwealth Parliament the power to make laws with respect to the people of any ‘race’, the race of Aboriginal peoples was explicitly excepted.

In 1967, these exceptions were removed from the Constitution at the famously successful Referendum of that year and Indigenous peoples officially became part of Commonwealth reckoning and lawmaking.

Even so, things moved slowly thereafter. While a Makarrata, or treaty, movement developed in the late 1970s along with a land rights movement, the treaty movement slowed to a halt and the land rights movement, at a national level, ceased altogether during the early years of the Hawke Labor Government in the face of entrenched opposition from the resources industry and State Governments in Western Australia and Queensland.

Then, in 1992, the High Court of Australia’s decision in Mabo momentously swept aside not only the political inaction of the preceding few decades but also the legal theory that Australia was a ‘desert uninhabited land’ where the native title of Indigenous peoples could not be recognised. Instead, the High Court found Australia’s common law did indeed recognise the continuation of native title following settlement. George Fletcher Moore was vindicated.

Mabo, in one fell swoop, achieved what Australian parliaments and government policies had never been able to achieve since settlement. It recognised the Indigenous peoples of the Torres Strait and the Australian continent as the ancient prior inhabitants of these lands. It recognised they were the possessors of powerful laws and customs that bound them to their countries. It recognised Indigenous peoples, as both citizens of Australia and as First Nations people could, by the Rule of Law, obtain orders confirming their possessory rights to their traditional countries.

Mabo led to the passage of the Native Title Act 1993, but it also loosened the shackles that had for so long, since settlement, constrained Australians from formally recognising in our Constitution the status of Indigenous peoples as the First Nations of Australia and seeking to conciliate a mature, post-colonial settlement with them.

At the forthcoming referendum, we have the opportunity to support the recognition of Aboriginal Peoples and Torres Strait Islanders in our foundation document, the Commonwealth Constitution, as our First Nations peoples, and to accord them a Constitutional right, denied them since settlement by the British, to make representations to law makers and Governments about laws and policies that impact their lives and cultures and may assist in reversing the impact of colonialism on past and present generations.

George Fletcher Moore saw the need for conciliation with First Nations peoples soon after the British settlement of the Swan River Colony. That need remains as strong today as it was then. The Voice will help to achieve it. I can’t help but think George Fletcher Moore would agree. That’s why I’m voting YES for The Voice.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

* By Michael Barker, Editor, Fremantle Shipping News. The author is a former judge of the Supreme Court of Western Australia, a former judge the Federal Court of Australia, and was the foundation President of the State Administrative Tribunal of WA

** You’ll find more Getting The Voice features right here

***Fremantle Shipping News supports the YES campaign

WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!