Now, some of Fremantle’s hidden treasures are in plain sight. Like The Buffalo Club in High Street that we featured recently in Freo Today. Others, like The Knowle, are well hidden. Not in plain sight. Indeed, kept well out of sight amongst the most interesting collection of structures that today make up Fremantle Hospital. But it wasn’t always the case, as this story shows.

The Knowle, as many aficionados of Freo’s heritage will know, was the very first Fremantle Hospital worthy of the name – opened in 1897, just 125 years ago.

Before that, The Knowle was the home of the very first Comptroller General of Convicts in Fremantle, Captain, later Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Edmund Yeamans Walcott Henderson KCB (19 April 1821 – 8 December 1896), who arrived, with his wife and infant son, on The Scindian with the first consignment of convicts on 1 June 1850.

You’ll notice the yet-to-be Sir Ed had then only recently attained the tender age of 29.

Mind you Sir Ed-to-be had the sort of pedigree that no doubt gave the Home Authorities every confidence he’d succeed in his assigned task. His father was Vice-Admiral George Henderson of the Royal Navy. Our Captain Henderson had distinguished himself in Canada – where he seems to have met and married his first wife, Mary – before getting the Freo job. Obviously, an organised and talented guy. He went on, later, back in the Old Dart, to run prisons and the police.

Sir Ed-to-be is not to be confused with Sir Reg – Admiral Sir Reginald Henderson – who in 1910 was the second Brit to suggest Cockburn Sound would be a good location for a naval base, and who eventually gave his name to what is today the burgeoning marine precinct of Henderson right near the locality of Naval Base just south of Freo. A naval base at Naval Base never happened, though it did happen on Garden Island just across the waters of Cockburn Sound. And to be fair, Henderson today could well be mistaken as some sort of naval base with so much marine industrial activity going on there.

But I digress, ever so slightly. Back to The Knowle. Apparently, it was designed by the Captain himself. And it was quite a home. Such a view it provided, sweeping across new Colonial Fremantle to Gage Roads, Rottnest Island and the vast Indian Ocean. We’d go so far as to suggest it would’ve been the finest setting for a home in the Colony when the building was completed in 1856. The convicts under Captain Henderson’s control not only built the Prison, that he also designed – based on the one at Pentonville back home in England – but also The Knowle.

At this point, however, Captain Henderson’s story has a sad twist to it that appears to end happily. In 1855, just before The Knowle was completed, his wife died suddenly from an illness on 27 December.

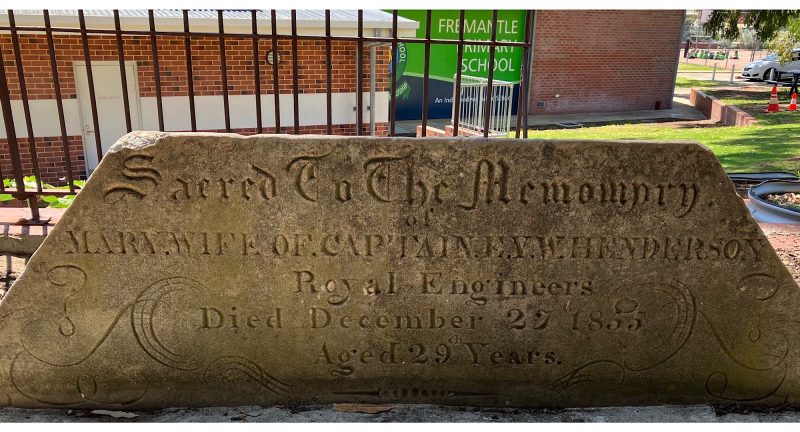

As an aside, but a very interesting one, Fremantle Prison website states that Captain Henderson’s wife was buried in the Skinner Street Cemetery in Fremantle and that the headstone from her grave can presently be seen at ‘Headstone Walk’ in Fremantle Cemetery. Following the further research of Garry Gillard from Fremantle Stuff, after we brought this information to his attention, it appears that Mary’s headstone, with a few other old ones, was re-erected in the grounds of Fremantle Primary School as part of a Heritage Garden, it being on the grounds of the original Alma Street Cemetery, where it is now to be found. Here’s the Fremantle Stuff entry. And here’s Mary Henderson’s headstone today at the school.

Following Mary’s passing, in February 1856 , Captain Henderson returned to England with his young son. In 1857, he was remarried, to Maria, in England. Then, in 1858, he returned to Fremantle with his new wife and family and lived in The Knowle.

So, 1858-1863 was Captain Henderson’s second period as Comptroller General of Convicts in Western Australia – during this time he continued establishing the convict system and the early public works department of the colony.

In 1863 , on 7 February, he left Fremantle for the last time on board the York with his wife and family to pursue his career in England and was soon enough appointed Surveyor-General of Prisons in the UK.

The story of The Knowle becoming the first Fremantle Hospital is in many ways the story of Fremantle, for from the inception of the Swan River Colony Freo was without a proper hospital. The story of how Freo eventually was favoured with one is actively recounted in the wonderful Fremantle Hospital: A Social History To 1987 by Phyl Garrick and Chris Jeffery and published by Fremantle Hospital in 1987.

After Captain Henderson departed Fremantle, The Knowle was used for a variety of purposes, the last one prior to 1896-7 being as a overflow space for the Lunatic Asylum – now the Fremantle Arts Centre. Dr Barnett, who ran the Asylum, was none too happy when he lost the political tussle over who would get The Knowle – him or the influential Freo folk pushing the Colonial Government, which had been invested with control of the building following the attainment of responsible government in 1890, to favour the residents of Freo.

Suddenly, in 1896, the Premier Sir John Forrest got behind the Freo hospital project, and then it happened.

Here’s how Garrick and Jeffery explain what happened next (at p 62-63, footnotes omitted) –

‘In (November 1896)…(Dr) Hope was was able to notify the Fremantle Municipal Council that work on The Knowle was nearly completed. Plans to convert the once-beautiful two-storey stone and plaster building – which had been erected by convicts as a residence for Captain Edmund Henderson the controller general of the convict establishment – had been made and discarded and made again in 1896. The final alterations and additions were shaped by an architect named J Herbert Eales, who married the daughter of James Lilly, first chairman of the Fremantle Hospital Board, appointed in 1997.

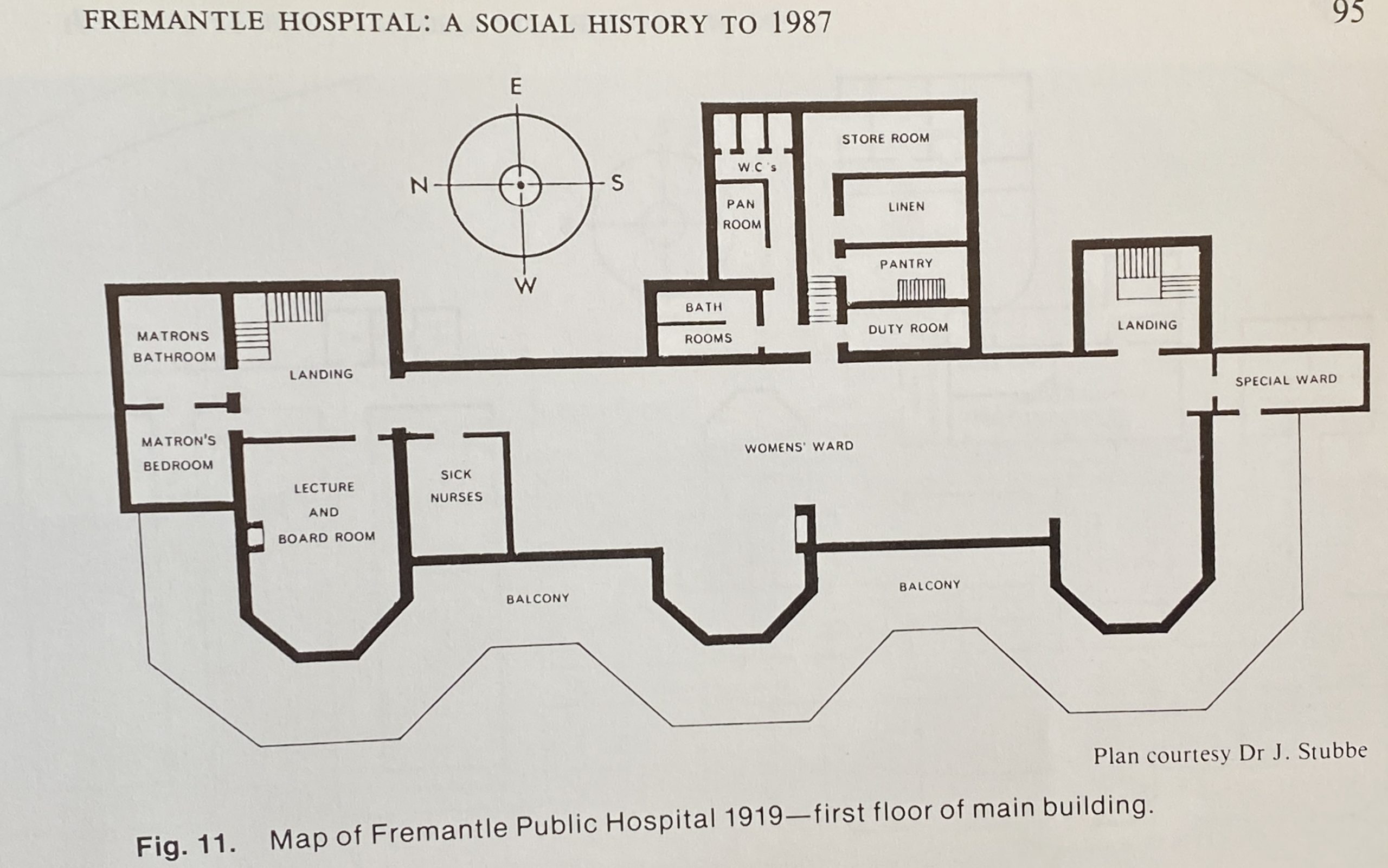

‘From mid-1896, R. Bushby, as the supervisor appointed by the Public Works Department, had faced a difficult task in restoring the building. Doors and windows had long disappeared from The Knowle and the shingled roof alternately leaked or splashed sunlight through large holes. The house on the hill was thought by many to be “ almost a total ruin“. Bushby renovated, repaired and supervised the construction of a new southern wing, extending the total area of the building by a third. Long French windows led directly to the ten-feet-wide verandah that wrapped around the front and sides of the house, from whence convalescent patients could catch the “invigorating sea breezes“ and watch the activities of the port with its shipping and river traffic. By December there were 15 rooms downstairs, including one for a dispenser, another for visitors, an office, a bedroom and a sitting room for matron, four wards and an “operating apartment“. A new kitchen with pantry and a larder were also added. Three nurses‘ bedrooms, four male wards, and women‘s wards were included upstairs, running the full length of the building. The south and north entrances were linked by a wide lofty hallway and throughout, the jarrah floors were polished until they shone. Two isolation wards were built outside, beside the laundry and wash house. Water was run from the prison pump into elevated tanks to give good pressure and the plumbing was unique for the times – based on principles of underground sewage, with all drains leading to outside surface sinks and then into a big dry well in the far corner of the grounds…’

By all accounts, according to Garrick and Jeffery, the transformation by Bushby ‘far exceeded the expectations of the most sanguine’ and it was remarked that this would be the ‘first hospital worthy of the name that Fremantle had had’.

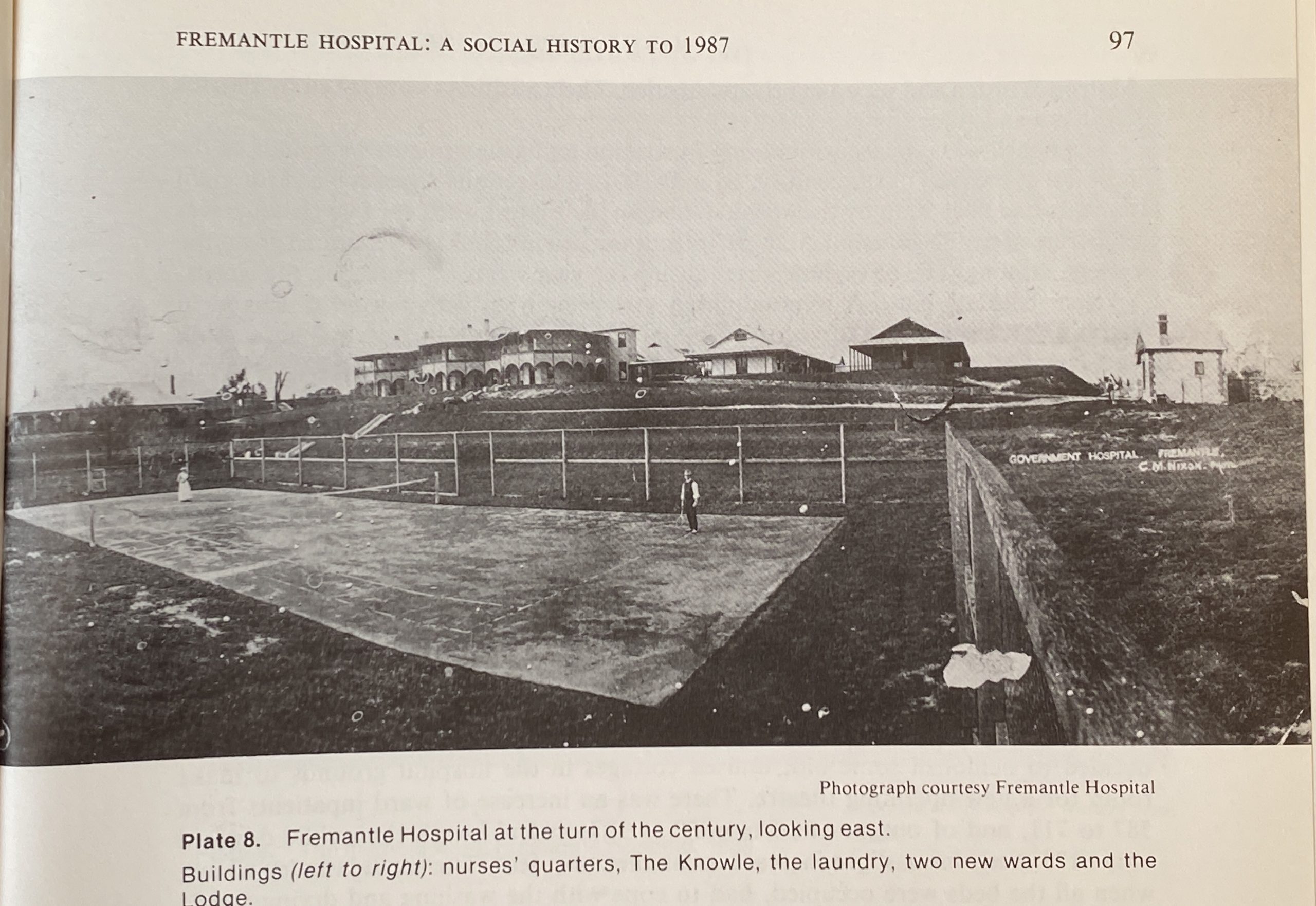

In the first six months of its operation, there was no shortage of demand. 432 patients were admitted, 169 of whom had typhoid fever. Typhoid was raging in Fremantle through much of the 1890s. Soon enough the number of beds was found to be inadequate and The Knowle’s first extension, a temporary, rectangular galvanised-iron ward for 22 patients was added, built from materials salvaged from Kalgoorlie.

Not long after that, a new brick nurses’ quarters was built to the west of The Knowle.

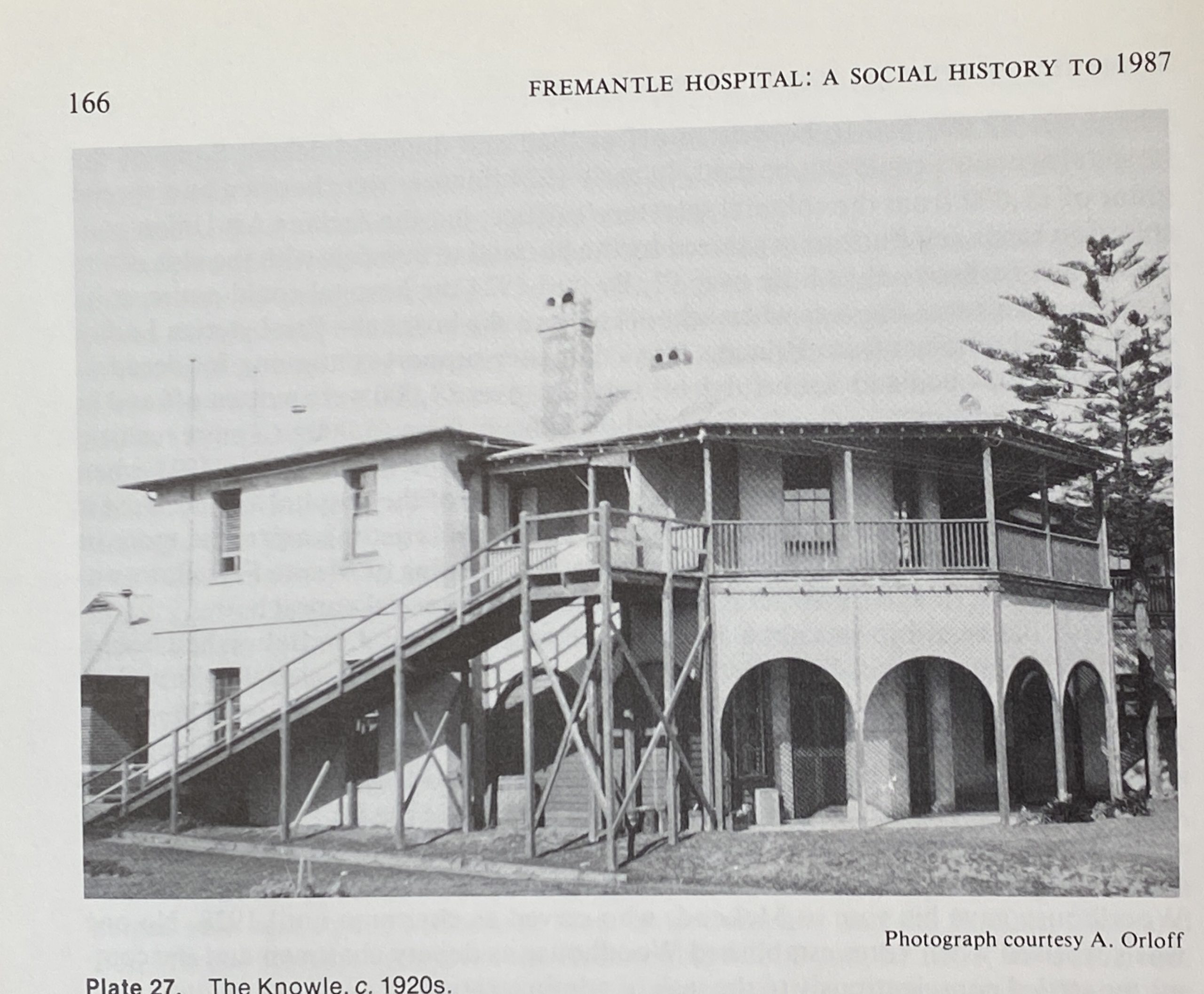

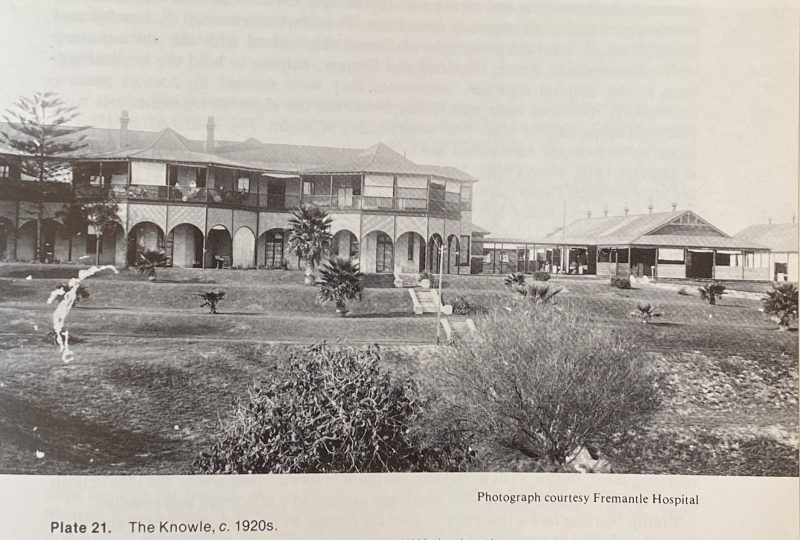

Here’s a photograph of The Knowle from the early 20th century, when some additions had been made on the southern side.

Things were happening at the hospital.

Soon a pathological laboratory was built.

Then an infectious diseases ward and a mortuary were built.

Then the bubonic plague hit Freo in the first decade of the 20th century.

It’s a timely reminder that infectious diseases come and go, in different forms, now and then – the Covid pandemic being the latest.

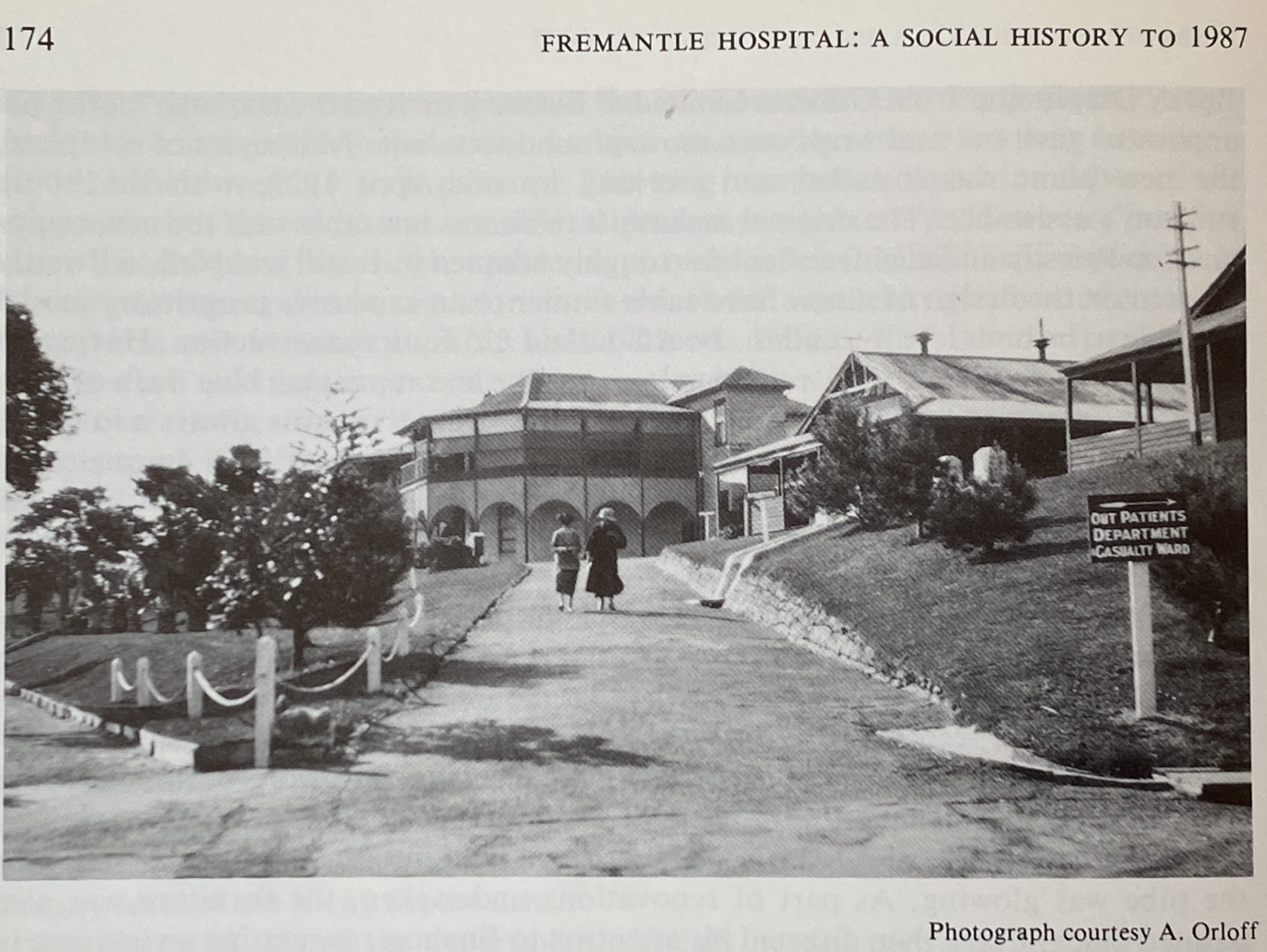

In the years that followed, further additions were built at Fremantle Hospital, including the Ron Doig Block in 1934 which was named for Ron Doig, the South Fremantle Bulldogs captain-coach who tragically died after being injured in the 1932 WANFL final against East Perth.

And then the William Wauhop Wing in 1960.

The Princess of Wales Wing opened in 1976 facing South Terrace and has become one of Freo’s most identifiable buildings.

In 1985, Woodside Maternity Hospital was incorporated into Fremantle Hospital and Health Service. In 2006, services transferred from that hospital to the newly acquired Kaleeya Hospital. Woodside Maternity Hospital is no longer in use and Kaleeya Hospital closed in 2014.

Fremantle Hospital then became a specialist hospital in February 2015, following the closure of its Emergency Department and transfer of its main tertiary services to Fiona Stanley Hospital.

But The Knowle lives on!

Today, the building is very much a part of the functioning hospital with the 1897 wards and rooms still occupied as offices and meeting rooms, as well as a comfortable Blue Room where the busy staff can occasionally relax between rounds.

As you wander around the old building, you can see and feel its heritage. And you can also mourn the lost views to the west, as your eyes come to rest on a taller, cream brick Princess of Wales block!

Not surprisingly The Knowle is listed on the State’s Heritage Register, which says of The Knowle –

‘The Knowle is remarkably intact, retaining the staircase made by the convict smiths in the prison smithies, and most of its interior fittings, floor and ceiling. The distinctive verandahs and semi-circular arched lower edge are still evident and the long axis is still recognisable for its three faceted projections, which wrap around the two storeys. The building is now obscured by the development of the hospital around it and it has lost its landscaped setting’

Here’s how it is described physically on the Register –

Originally a 2 storey masonry building, rendered and lined-out externally with 2 storey verandahs. The original shingle roof was later replaced with corrugated iron. The main building has three large faceted bays along its western facade. These bays are encompassed by the two storey verandahs, covered by a reduced pitch extension of the main hipped roofs over the bays. The original verandah detailing has been replaced. The upstairs verandah has been enclosed. There are French doors to the ground floor rooms. Ornamented timber and iron staircase leads to the first floor from the entrance hall. Secondary staircase, probably of later construction, has turned timber newels and balustrading. The building was later altered for hospital use and major extensions and alterations in a number of stages were added to the southern side of the building and internally.

Here’s a pic of the main staircase.

And here’s one of the secondary staircase.

There are though some statements made in the Register of Heritage Places which we tend to think are confusing, especially having regard to the extensive research found in Garrick and Jeffery, some of which we have set out above. For example, it is stated in the Register entry that –

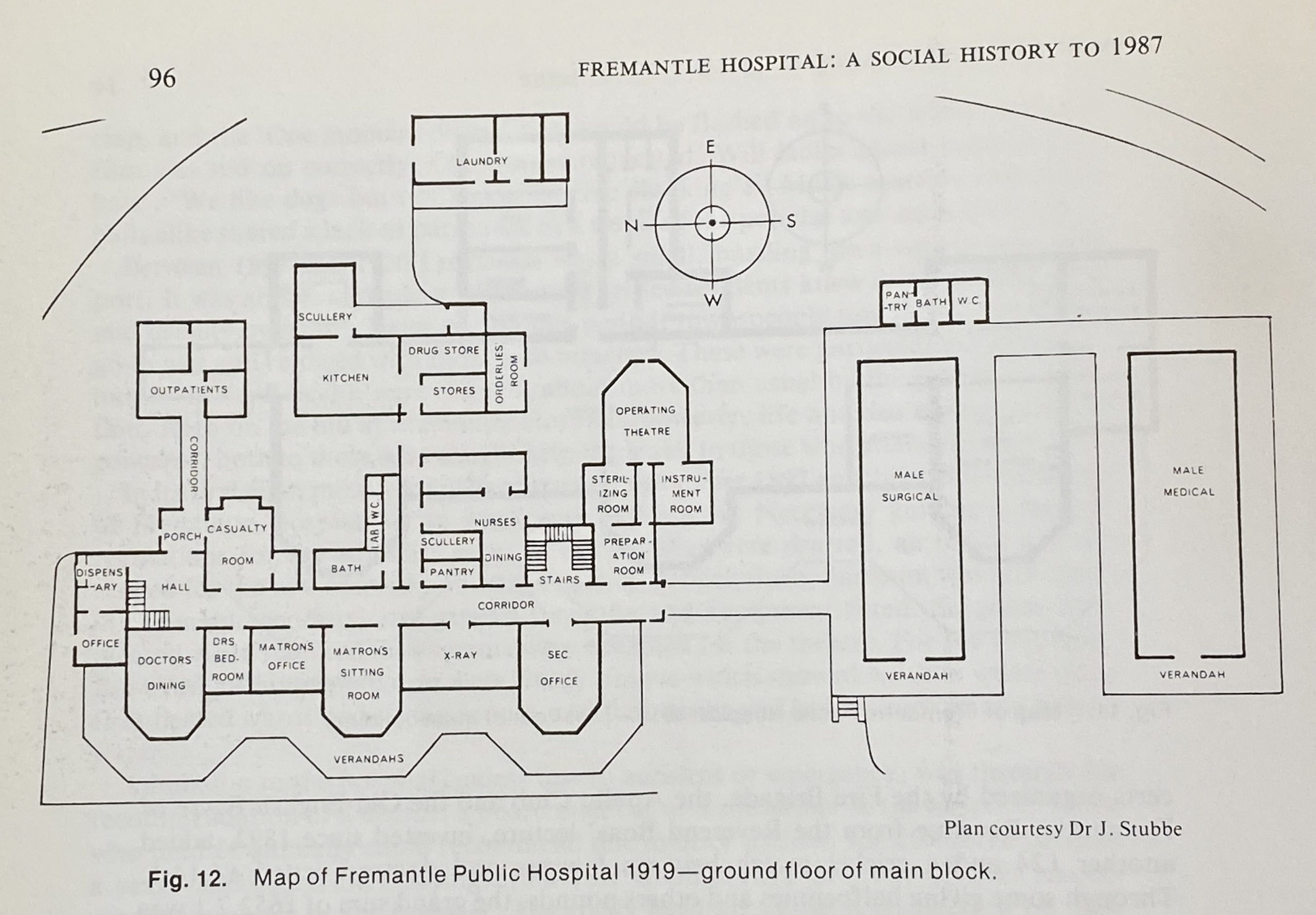

‘Alterations and repairs were undertaken by J Herbert Eales. In January 1897 it opened as a 52 bed hospital. Further extensions were built under J H Eales in 1903, which included operating theatre, outpatients’ quarters, examination rooms, waiting and consulting rooms. The old house was extended by one third by PWD architect Charles Rosenthal who later had a distinguished architectural and military career.’

Plainly the 1896 renovation of The Knowle included, as Garrick and Jeffery state unambiguously, ‘the construction of a new southern wing, extending the total area of the building by a third.’

Perhaps Charles Rosenthal was involved, but Garrick and Jeffery plainly state R Bushby was the PWD supervisor.

As a matter of interest, Rosenthal, who later gained quite a military reputation both before, during and after the First World War, as disclosed in his Australian Dictionary of Biography entry, was employed as a draughtsman or an architect in Western Australia during the years spanning the renovation and extension, by a third, of The Knowle, although it appears he had left The West as of 1898. The Dictionary of Biography entry notes that Rosenthal was elected an associate of the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects in 1895. It seems soon after he became a draughtsman in the architectural division of the Department of Railways and Public Works in Perth. Then he moved to Coolgardie, presumably in his PWD position. Nonetheless it appears he remained involved in plans for the Perth law courts, the Free Public Library and the Royal Mint. Having decided to return to Melbourne after his health was threatened by typhoid — he was also bankrupt, apparently — Rosenthal sent his wife by ship and he then set off for Melbourne on his bicycle in November 1898. By all accounts he made it across the Nullarbor and then pursued his brilliant career.

The entry on The Knowle in Fremantle Stuff by Garry Gillard also supports the view that The Knowle was extended by a third under Bushby’s supervision. As Dr Gillard points out by reference to the photographs of The Knowle post 1896, the southern third doesn’t display any chimneys; they’re only to be seen on the northern two-thirds of the home. One may agree that this is confirmation that The Knowle, until the 1896 renovation and extension, was just the northern two-thirds.

So there we have it – The Knowle, a hidden heritage treasure in anything but plain sight and now a part of the amazing collection of buildings that make up Fremantle Hospital.

We look forward to the next Freo Hospital open day when Freo folk can visit The Knowle and get a sense for themselves of what once was, and still is today.

By Michael Barker, Editor, Fremantle Shipping News

WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

* And don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!