Ideas are powerful, but when it comes to a constitutional amendment, they need to be put into words before they can be debated seriously.

AAP/Aaron Bunch

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has finally given us the first draft words for a constitutional amendment on an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to Parliament. They are as follows:

- There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

- The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to Parliament and the Executive Government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

- The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to the composition, functions, powers and procedures of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

It is a simple and elegant proposal, which demands little but offers much.

What would the amendment do?

The only requirement of this amendment is that such a body exist. It leaves to parliament all the decisions about how it is comprised and operates. This balances stability and flexibility.

The constitutional demand that the body exists ensures it cannot be cancelled at the whim of a future government, or left to die of neglect. If the Australian people, in a referendum, have demanded the continuing existence of a Voice, this puts serious pressure on both the government and Indigenous Australians to make it work productively.

But if, over time, it ceases to work well, parliament has been given the flexibility to change the composition of the Voice and how it operates, so that it can properly fulfil the role voters intended for it. This avoids the problem of becoming stuck with a dysfunctional body and ensures the democratically elected body, parliament, has full power to make necessary changes.

The role of the Voice will be to make representations to parliament and the government about matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The intention is to ensure parliament and the government are better informed when they make decisions.

There are two main aims of this proposed amendment.

1. Constitutional recognition

The first is constitutional recognition of Australia’s Indigenous peoples. They are not currently mentioned at all in the Commonwealth Constitution. Many politicians, including John Howard and Tony Abbott, have proposed that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples be recognised in the Constitution. But recognition can take different forms.

The type of recognition proposed in this current amendment goes beyond just words on a page. It is no mere formulaic opening recitation.

True recognition involves giving another person enough respect to stop and hear their voice. This proposed amendment provides real recognition in daily life by ensuring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have a voice, and can be heard about laws and policies that are likely to affect them.

2. Practical change

The second aim is to achieve practical change. It is well known that Aboriginal policies and laws have been far from successful in the past. This is unsurprising, since those who make laws and policies in Canberra are largely removed from the impact they have on the ground.

With the best will in the world, it is impossible truly to understand the issues affecting a person’s life without walking in their shoes. Giving the people who have walked in those shoes a voice to inform governments about the likely effect of proposed laws and policies, and suggest how they might be altered to be more successful, will hopefully lead to better practical outcomes.

The question

The prime minister has also identified some proposed wording for the question to be asked in a referendum. Its wording is a little unusual.

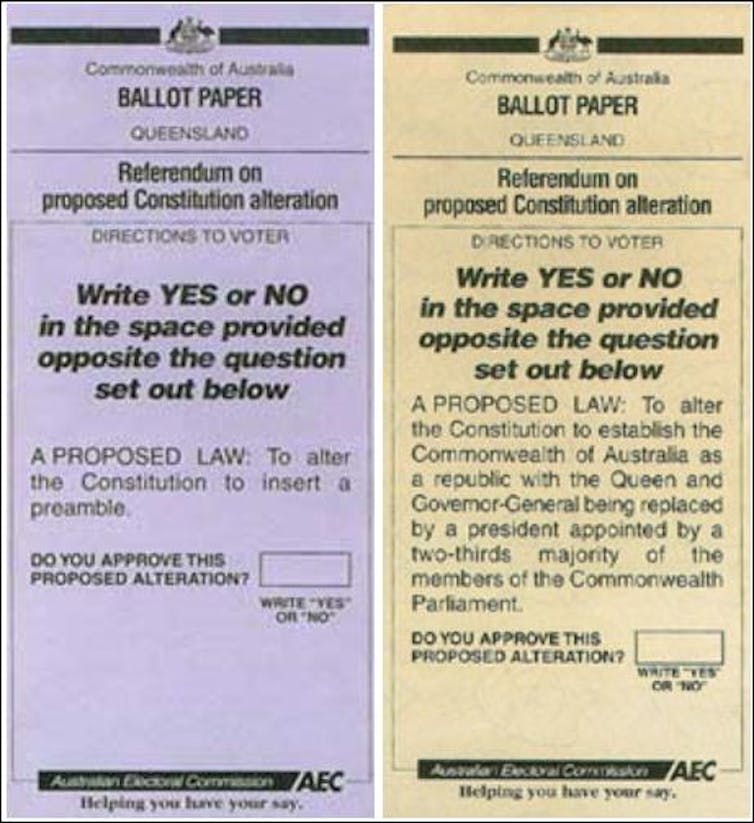

Section 128 of the Constitution requires a referendum to change the Constitution, and says that it is passed when a majority of electors overall and a majority of electors in a majority of states “approve the proposed law”.

So the question needs to be formed in such a way that voters are approving the “proposed law” to change the Constitution – not approving an idea, a principle or the creation of a new body.

Under the current law, a referendum ballot paper sets out the long title of that proposed law to alter the Constitution, and then asks “Do you approve this proposed alteration?”. A box is then provided for the voter to write either “Yes” or “No”.

Australian Parliament House

For example, the ballot could say:

A PROPOSED LAW: To alter the Constitution to establish an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve of this proposed alteration?

In his Garma speech, the prime minister stated the question would be:

Do you support an alteration to the Constitution that establishes an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice?

While that question is clearer, it does not comply with the current law, which presumably the government proposes to amend. But the government would need to make it clear on the ballot paper that the voter was approving the proposed law, because this is what is required by the Constitution.

There is also a lack of clarity about whether the constitutional change would actually “establish” the Voice, given that legislation would first need to be enacted to determine how it is comprised and to establish the mechanism for choosing its members.

However, these are small matters that will no doubt be worked through in the ensuing debate.

Consultation and education

Now that draft wording is available, the proposed amendment can be discussed with greater authority and clarity. Suggestions of a “third house of parliament” and other exaggerations can be readily dismissed.

Wisely, the government has shown itself open to adjusting the wording if necessary. The next stage in the process is one of consultation and education, so the Australian people can feel confident they are well-informed when they come to vote in any future referendum.![]()

Anne Twomey, Professor of Constitutional Law, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

While you’re here –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!