I worked in Customs and Excise for thirty years from 1960 to 1990. Mostly in Fremantle, but also Perth airport. Hated the airports !

On Customs business I was lucky enough to visit and work in every port on the coast between Esperance in the south, and Groote Eylandt in the Gulf of Carpentaria. My longest terms out of Fremantle were spent in Port Hedland, Derby and Darwin.

The port of Fremantle was a different place back in the sixties. A very different place. Only the rich flew, and the post war migration boom had not ended, so passenger ships arrived every few days full of British and European migrants anxiously looking towards establishing a new life in Australia.

Credit pocketoz.com.au

And when these ships, having visited the eastern Australian ports, came back as last port Fremantle on their way overseas, they were full of young Australians heading off to the ‘Old Country’ (including many very nice looking girls I noted!) Crowds flocked down to ‘Freo’ to welcome and farewell them. The passenger terminals at ‘F’ and ‘G’ were quite civilised places and a far cry from the cargo sheds they replaced.

Credit City of Fremantle

Cargo ships continuously flowed through the port discharging and loading general cargo into the sheds on Victoria Quay and to a lesser extent North Quay. No container ships until 1969.

The west end of Fremantle was full of hotels but also shipping agencies and customs brokers. The latter were the people who carried out the often complicated process of clearing commercial imports of goods through customs. Our old Customs House sat proudly on the corner of Cliff and Phillimore overlooking the shipping square.

With so much activity visible during a ship’s arrival, discharge and/or loading, and then departure, very little was known or said about its responsibilities to the Australian government. Did it just arrive, sail around the coast discharging and loading and then sail away back from whence it came?

Well no. Of course not! This was Australia and we had lots of rules.

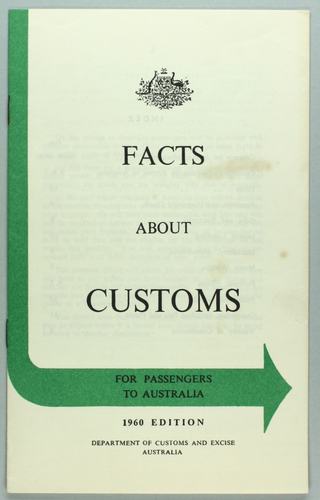

All ships (except Navy) arriving anywhere on the Australian coast from overseas had to provide a fairly substantial amount of paperwork relating to crew, the crew possessions, and the ships store’s which attracted a high rate of duty. That is, alcoholic drinks and cigarettes.

Also, we required information about pharmaceutical drugs on board through the sailing dates from previous ports and, of course, the port clearance from the previous port. They had to also present cargo manifests, but that was done by the ships agent who fronted up at the Customs House. Once a ship arrived on the Aussie coast it really became part of Australia. If a census happened to be on, all ship’s crew were counted as part of the population. Even ships which were sailing between Australian ports.

Customs and Excise were the controlling body for most of these impositions. The embodiment of it all was the ‘Boarding Officer’. The Boarding Branch, located in the Customs House, comprised a Boarding Inspector, Senior Boarding Officer, six Boarding Officers and the clerk. The BO worked alone on all ships except the passenger ships on which he had two or three helpers brought on to do specific jobs.

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

In 1966 at the tender age of 23 I was thrown into this environment as a BO. We worked 9 to 5 office hours but, because shipping did not, we worked a fair bit of overtime.

Most ships “knew the score” and arrived with documentation complete. But there were exceptions. Japanese tuna boats arrived with no documentation whatsoever and 30 crew on board, none of whom spoke any English. And we spoke no Japanese!

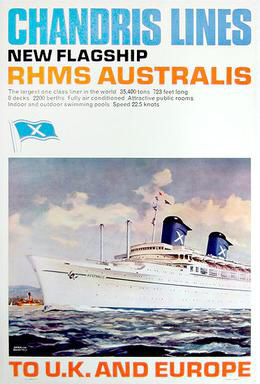

At the other end of the scale were passenger ships, the likes of P & O’s SS Oriana and Chandris Lines’ SS Australis, carrying crews of well over 600. Each crew member had to complete a written declaration, so it was a massive amount of paperwork.

We boarded overseas arrivals in ‘the roads’ with the pilot, who guided the ship into port, and the quarantine doctor, who was there to examine the crew and grant pratique. ‘Granting Pratique’ was a carryover from the days of sailing ships who might have arrived with plague on board.

Because of this, it could only be done in daylight, that is, between sunrise and sunset. Well, you couldn’t expect the doctor to be able to identify the pox in the dark could you! The ship had to sail the yellow ‘Q’ flag until cleared and could not proceed into port until the doctor said so, which occasionally caused friction between the pilot and the doctor.

I soon had to get used to getting out of bed very early in the morning and driving through the blackness from East Victoria Park to Fremantle. I would embark on the pilot boat waiting at the Forrest Landing at B shed and, in all weathers, sail out to Fairway Buoy where we came alongside the ship and then climbed up the rope ladder to get aboard. Thence to check all documentation to ensure it was properly complete, and to physically check quantities, but not before having a nice cup of coffee and maybe breakfast in whatever form it took. British ones were best.

A pilot showing how it’s done today!

If I was boarding a passenger ship, there might be up to 30 in the party because we had to do the immigration processing of the several hundred passengers. That is, stamp their passports with either a permanent entry stamp or a temporary entry stamp.

Depending on how well the paperwork had been completed, time spent on board could be easy or difficult. The easy ones were the regular callers because they knew what was required and mostly completed the paperwork correctly.

In 1966 regular callers were the ‘Bakke boats’, part of the Knutsen Line, (Lloyd Bakke, Astrid Bakke, Kristin Bakke and others), the British India Steam Navigation Company, known as the ‘B I Boats’, (the new Harbour Master’s father worked on B I boats) that is, the Chandpara, Chakdina and others, (they served brilliant curries on board and were my introduction to proper Indian curries long before Indian restaurants appeared in Perth).

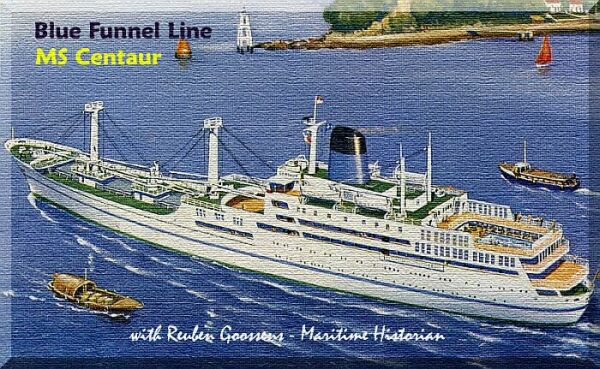

Also the Blue Funnel Line, Charon and Gorgon, replaced by the Centaur in 1964, the British Bank line, the Japanese ‘K Line’ (I eventually memorised ‘K’ stood for Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha) who are still servicing the port, and of course the mighty passenger ships.

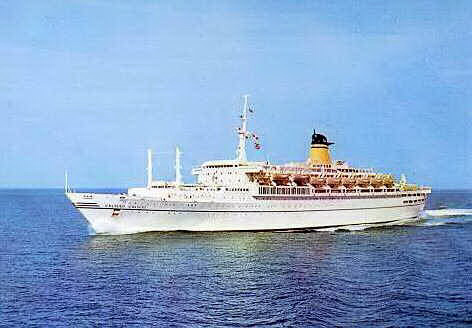

P & O’s Oriana, Orsova, Orcades; Lloyd Triestinos’s Galileo Galilei, Guglielmo Marconi; Sitmar’s Fairstar, Fairsky, Castel Felice; Shaw Savill’s Northern Star, Southern Cross; Flotta Lauro’s Angelina Lauro, Achille Lauro; and the Greek Chandris Lines (sometimes cruelly called the Chundrous Lines) Australis, Ellinis and Patris. And there were many others.

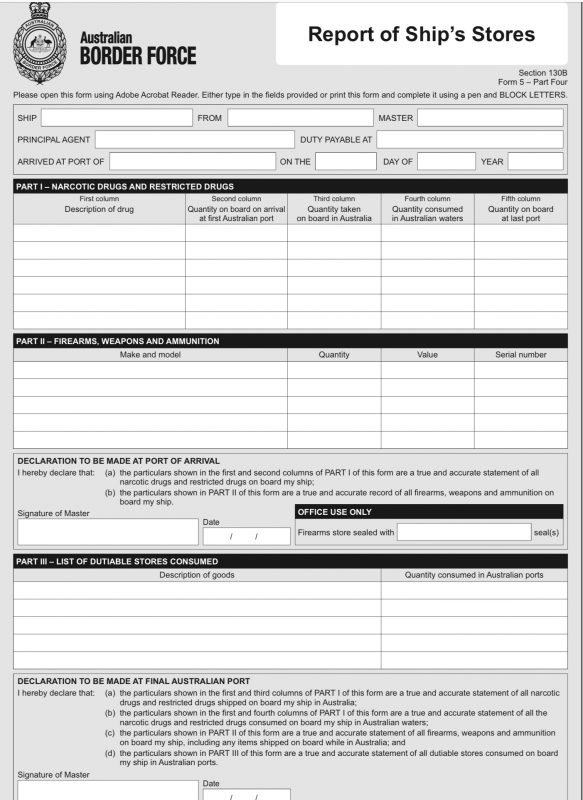

The Master signed the completed documents but they were prepared by the Purser or maybe Radio Officer. Individual crew members declared their transistor radios etc and we checked physically to ensure it was all correct. The two documents which interested us most were the high duty stores list, the form 3, and the crew possessions list, the form 5.

All high duty stores had to be listed on the stores list and that portion not required was sealed away in the ‘Bond Store’ with a Customs seal on the door. A quantity was held out or released for consumption on the coast and, on these quantities, duty was charged.

So, in sailing around the world, when a ship hit Australia the crew, and the passengers, had to pay double for their drinks. What better way to become part of Australia! Fortunately, all that has now been scrapped. But back then, we had to satisfy ourselves that quantities shown as released, were correct.

The Oriana had about thirteen storerooms, bars, restaurants and plain storage places where they kept their releases. Every one had to be visited and contents counted. It was a long day with lots of walking. Every bartender or storeman greeted you like a long lost friend and wanted you to have a drink with him! In this regard every passenger ship was much the same. When the ship came back to Fremantle, final port on its way back to the UK, the same process happened, thus we could confirm how much had been consumed on the Australian coast.

Fremantle was generally the “first and last” so we did this on almost every ship.

The other document was the infamous ‘Form 5’. Every crew member had to sign this, and alongside his signature, declare his high duty possessions. The pages were very big to accommodate the names of several crew members. Consider the Oriana with upwards of 700 crew!

The From 5 still lives, would you believe it! Although it’s a tame version of the complex form a BO had to administer in the day!

Consider also the Japanese tuna boats which arrived with no paperwork (and no English) and we had to organise them to complete the document correctly!

Correct completion of items like transistor radios required brand names, serial numbers etc and this is what presented the challenges. We soon became very accomplished at locating the serial number on a radio whilst the crew member stood there swearing black and blue none existed.

There was a third important document. The official crew list, called an M&S 11, which was checked by us on board against the ship’s official crew list to ensure it conformed with it. It was a carryover from the British Merchant Shipping Act of 1894. As crew signed off the ship or signed on the ship the M&S 11 was noted, so it was a record on the ship of the crew on board at any one time.

The paperwork had to be completed and presented at the first port of call and then, for the rest of the voyage around Australia, the papers stayed on board the ship sealed in a large envelope. This was opened and the papers used by the boarding officers in each of the ports visited.

Fifty years and more on, are the same bureaucratic procedures used on overseas ships? Of course not. But for me, and others lucky enough to be posted into the Boarding branch back then, it was a job we would never forget.

When you stepped, or clambered, on board you really left Australia and entered the world of the nationality of the crew. You grew to appreciate the characteristics of the different nationalities, and who were best with paperwork. When the jobs were put up on the board the afternoon before you knew just what kind of day you had ahead of you.

The great appeal of being a boarding officer was that you worked on board the ship closely with all the crew. You were fulfilling the role of Customs boarding ships on arrival that was an age old practice.

The ships agent and the local providore spent a lot of time on board too, but they generally spoke only to the master.

You though were first on board on first port arrival and last to leave the ship on final port departure.

Like many, I think, I long for the Fremantle of old. It was an honest to goodness working port but access was permitted to most areas.

For me 1966 was an unforgettable year and I thought it could not be bettered. But in 1967 1968 and 1969 I had even more unforgettable years doing the same kind of work mostly in Port Hedland, Derby and Yampi Sound and Darwin, but also all the other ports. But they are each other stories!

* Michael Metcalf is the author of On Customs and Coffins: A Memoir available here.