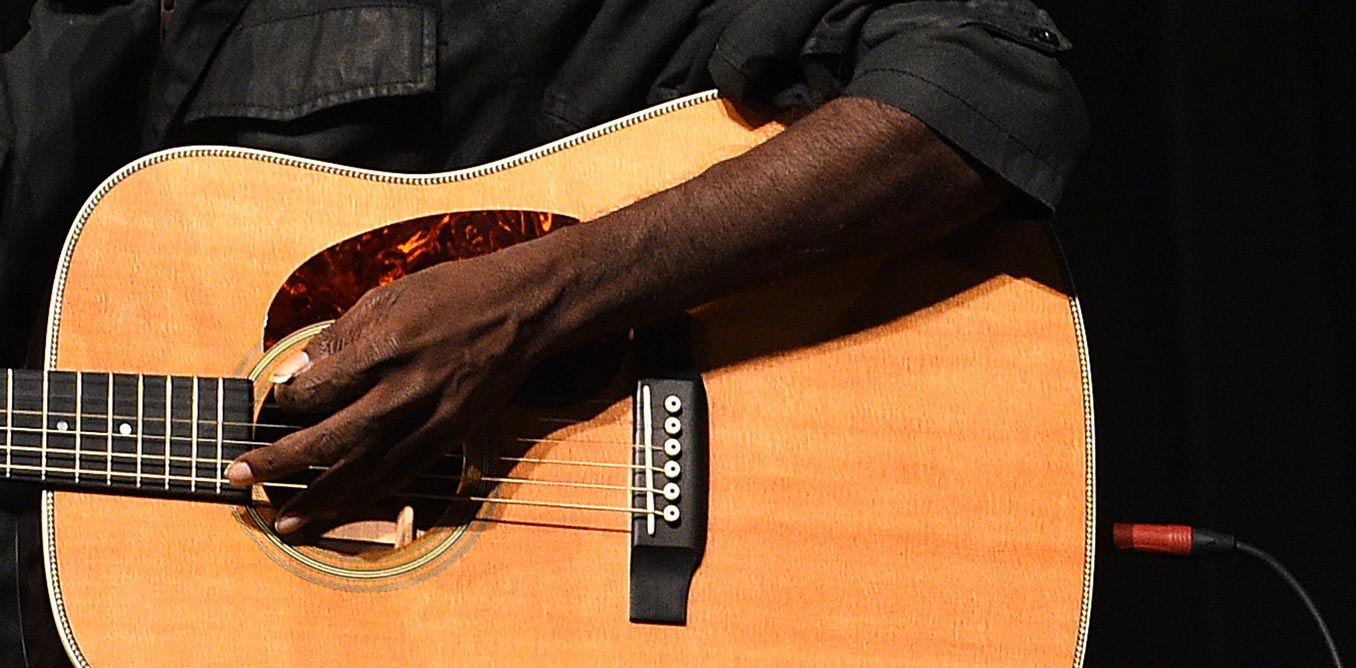

The music of Dr G. Yunupiŋu — who has died at the age of 46 from complications arising from a childhood illness — is steeped in the culture of his people, the Yolŋu of northeast Arnhem Land, and specifically in Manikay, the sacred song tradition performed by the Yolŋu when conducting public ceremonies.

Manikay is a medium through which the Yolŋu interpret reality, define their humanity, reckon their ancestral lineages, and evidence ownership of their hereditary homelands through their ability to sing in the tradition of their ancestors.

Dr Yunupiŋu drew immense strength and inspiration from this tradition, and particularly from the Manikay repertoires of his own clan, the Gumatj, and his mother’s clan, the Gälpu. Direct musical and lyrical quotations and references to ancestral themes drawn from Manikay repertoires are present throughout his original songs.

For example, both the melody and lyrics of the initial chorus of I was Born Blind (2008) stridently reference the strength that Dr Yunupiŋu drew from the eternal Gumatj saltwater crocodile ancestor, while the soulful lyrics of Bakitju (2011) echo sentiments of homesickness and loss found throughout Manikay repertoires.

In this way, Dr Yunupiŋu’s music has made Yolŋu values, as expressed through the Manikay tradition, accessible to audiences all over the world. Simultaneously, it has extended a decades-old popular music scene in Arnhem Land that deliberately encourages local youths to follow their culture by singing in their own languages.

Though born congenitally blind, Dr Yunupiŋu taught himself music from a young age and exhibited prodigious gifts. In his teens, he performed and toured the world with his family from Yirrkala in the band, Yothu Yindi, before returning to Galiwin’ku to form the Saltwater Band with his family there in the late 1990s. In 2008, his career as a solo singer and song-composer began.

Dr Yunupiŋu’s music is steeped in the culture of his people, the Yolŋu of northeast Arnhem Land.

During the late 1990s, around the time that Skinny Fish Music recorded the Saltwater Band’s first album, Gapu Damurruŋ’ (1998), I had the privilege of meeting Dr Yunupiŋu and spent considerable time in his midst. At the time, I was undertaking the first comprehensive study of Arnhem Land’s contemporary popular music scene and, when we spoke about his music, he stressed the fundamental importance of music as a means of encouraging Yolŋu children to follow their culture.

The Saltwater Band’s music was full of kinetic energy and youthful exuberance with fast and frenetic songs that blended ska rhythms with gospel harmonies commonly heard among church choirs on Elcho Island.

Yet also present were the seeds of the slower, more contemplative style for which Dr Yunupiŋu received international acclaim as a solo artist. In songs such as I was Born Blind and Bakitju, which Dr Yunupiŋu later recorded on his solo albums, the exceptional beauty of his voice rang true in a way that always left audiences completely enthralled.

Even before the Saltwater Band recorded its first album, Dr Yunupiŋu’s songs were wildly popular among Indigenous communities with thousands of copied and re-copied tapes of the band’s demos and live performances circulating throughout the Top End and Central Australia. Everywhere he went to perform on the regional circuit of Aboriginal festivals in Arnhem Land and beyond in the late 1990s, audiences would expectantly wait for him to appear on stage.

I can vividly recall the closing night of the Miliŋinbi Festival in November 1997, when the Saltwater Band was the final act to take the stage. Bands from Miliŋinbi and neighbouring towns played into the early hours of the morning and there had been whispers throughout the evening that Dr Yunupiŋu would indeed perform.

Entire families stayed outdoors in the cool post-midnight air to experience the catharsis of hearing him sing live and, when his performance finally brought the festival to close around 3am, the audience was utterly transfixed. His generous spirit shone through and his voice was nothing less than transcendent.

It was not until Dr Yunupiŋu’s passing that I realised he and I were the same age, and now I wonder why it is that his life expectancy was cut so short. What systemic disadvantages could have been addressed to prevent him and so many others living in remote Indigenous communities from dying so young. And what, amid so many failed efforts past and present to improve health outcomes for Indigenous Australians, can yet be done to prevent others from unnecessarily dying so prematurely?

In remembering Dr Yunupiŋu, Australia celebrates the life of a man who overcame immense personal and social disadvantages to make the world a better place though his love of music. Yet it is also confronted by a clear and present need to do better in supporting the health and wellbeing of Indigenous people living in remote communities.

Aaron Corn, Professor of Music and Director, Centre for Aboriginal Studies in Music (CASM) and National Centre for Aboriginal Language and Music Studies (NCALMS), University of Adelaide

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.