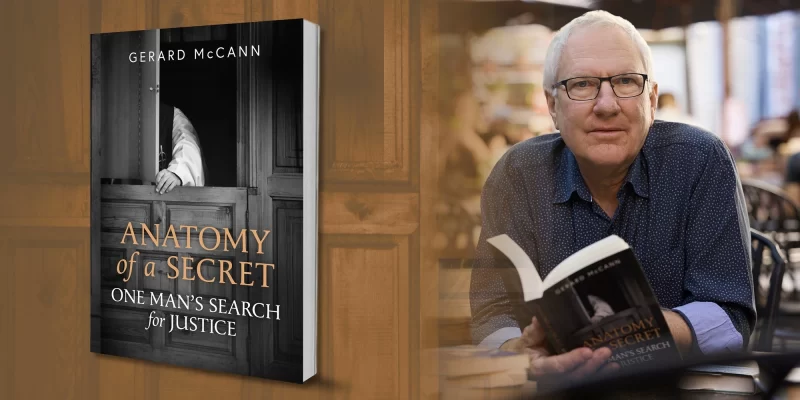

Last Thursday evening, in the almost tranquil surrounds of Kidogo Arthouse, Bathers Beach, Fremantle, a large group of Gerard McCann’s family, friends, professional and writer colleagues, and admirers gathered for the launch of Gerard’s book ANATOMY of a SECRET – ONE MAN’S SEARCH for JUSTICE, just published by Fremantle Press.

It was a moving experience. Books like this are rare and the audience sensed the importance of the occasion. Some of those gathered at Kidogo for the launch of the book, like its author, had first hand experience of its traumatic subject matter – sexual abuse of children.

Following Gerard’s speech about how and why he came to write the manuscript, find it short-listed for the 2022 Hungerford Prize, and now to see it published by Fremantle Press saw those gathered at the launch of the book quietly applauding Gerard for a sustained period in acknowledgment of his courage in revealing the anatomy of the secret he bore for so long, as a boy, a teenager, a young man, and as an older man, as well as his personal search for justice from the Catholic Church.

It’s a book many will want to read, confronting as it is. It is a book that in a real sense is generational, from a period after the Second War when Australia was changing politically, socially, economically and certainly culturally, a period when commitment to formal institutions was being questioned and the hold of patriarchal figures like Christian leaders over their flocks was breaking down. Most recently in Australia, as in many other parts of the world, the revelations of the sexual abuse of young people, especially boys, suffered at the hands of those like Gerard’s parish priest and friend of the family who were meant to be their trusted guardians and mentors has left our community horrified and bereft.

Caroline Wood launched Gerard’s book on Thursday night. With her permission, we republish her launch speech here. No better review of the book and its significance could be provided. Like the book itself, Caroline’s speech launching it deserves a wide audience.

Caroline Wood is the Co-Founder and CEO of Centre for Stories based in Boorloo. She is a member of the Australia Council, Board of Creative Australia and Encounter Theatre. In 2023, Caroline was appointed as a Member (AM) of the Order of Australia for significant service to literature as a publisher, and to the community through a range of roles. She is the co-founder of Margaret River Press and the Australian Short Story Festival, and has served on the boards of Amnesty International Australia, the Small Publishers Network, the Margaret River Augusta Tourism Association, and PEN Perth.

Here’s Caroline Wood’s launch speech.

Even in our chatty, confessional culture, with selfies and social media, some subjects are too painful, too unwieldly to put into words. To write of sexual abuse is to remember the grief and horror of the past. To re-live the anguish of secrets, long denied and pushed away to the darkest recesses of our minds, our very heart. Anatomy of a Secret accomplishes the writing of pain simply and brilliantly.

Anatomy of a Secret is a memoir of the grief and loss that accompanies abuse. It is about a life stolen and of the corrosive ongoing power of secrets and silence. It is also a memoir about the resilience of one person. Resilience in the face of institutional might.

I was enraged and saddened as I read of the heartbreaking journey endured by Gerard as a child by an institution that I too belonged. I was awed by the resilience of his spirit as he endured the despair of a universe without parent, friend or God. It’s a memoir that is brutally honest on every emotional level, yet the reader does not despair, the reader can only marvel at the resilience and courage that has shaped every moment of Gerard’s life.

It is a story of crushing institutional failure and about the control and power of the Catholic Church. It details how post-traumatic stress manifests through a recurring nightmare – a nightmare that leaves Gerard voiceless, feeling exhausted and empty.

In unadorned prose, Gerard recollects his quintessential carefree West Australian childhood –summer picnics, days at the beach, imaginative theatre plays, the love of family, spending holidays with relatives in the country, and the other part of his life – devotion to faith and servitude to the Church as an altar boy, saying the rosary, taking sacraments and confessing his sins. In the same crisp prose, he writes of the first instance of the sexual abuse that took place in the sacristy by the new priest who he finds himself alone with – Father Leo Leunig. A beckoning finger is followed by an unimaginable act of abuse to a child– Gerard is held by the shoulders and Father Leunig’s hand slips down the front of his pants till he finds his penis. An act that left Gerard confused, terrified and ashamed. This was the first of many more acts of sexual violation against Gerard.

Gerard endured four years of abuse and during this whole period remained committed to the Church – He writes that ‘ I knew in advance which week Leunig would be on roster and, given the spell that his secret had cast over me, was impotent to do anything else than turn up. To refuse to serve would have raised questions with my parents that I could not answer. I had not the courage nor the resourcefulness to be deceitful or devious, nor risk tainting my pious self-image. There was simply no questioning of any commitment to the Church.”

And yet during this period, despite visible changes – change in his demeanour, a noticeable decline in his school achievements, the adults in Gerard’s life did not ask any questions or come to his rescue.

Gerard was left to stop the abuse himself, at the age of 14 Gerard told Father Leunig, ‘I’m not doing this anymore’. Liberating at one level but not freeing, the trauma was set for life. It was deeply rooted. Like many others Gerard continued to “live”.

He succeeds in improving his school results, easily passed the final exams at Tech, won a cadetship, began earning a wage, bought a car, got a place at university through a highly competitive process. Gerard, like many young Australians, travelled through Europe on a student wage, graduated from university and joined an architectural firm, enjoyed shared living and developed a relationship with a young woman Louise, undertook more travel and did a stint in a kibbutz. Gerard got married, renovated a house, had children, worked and became a respected heritage architect. But his life was peppered with many moments of unexplained bursts of anger, bouts of depression and self-loathing.

‘There was no name for this angry depression with its passive-aggressive silences, its extreme and raging responses to criticism or blame, and its blaming of everyone else for conflicts – they would one day be given a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.’

At the urging of Louise, at 37 Gerard takes his first step towards understanding the cause of his emotional and mental state. It took months, years to unpack the trauma and for Gerard to gain an understanding and process the source of his anger, his internal war led to great sadness about what could have been and fuelled his rage against the Catholic Church.

How does something like this happen, as it was and has been happening to thousands of others around the world ? The power of the Church is not to be underestimated. As Catholics, you are indoctrinated that the priest is “another Christ,” that “veneration and respect” should be given to him. The priest is the representative of Christ, and in some way, he is himself a continuation of Christ. The role of the congregation is to respect and honour, give generously, give thanks, pray faithfully, and, above all, to obey. And obey we did!

Gerard’s parents were intensely Catholic – his father a pillar of the church, his mother a strong believer – both desperately doing everything to ensure they were securing their passage to heaven by obeying and been servants of the Church. Father Leunig occupied a special position in the McCann family, he worked to gain the trust of Gerard’s parents. He also knew they had deep religious convictions which made it all the easier for him to take Gerard and later his younger brother away for weekends in the country. The power of the priests is inextricably linked to their sacred office which exempts them from accountability and is based on a theology of the priesthood that makes them occupy a special place in the eyes of their congregation. When Gerard told his father of the abuse, his reaction was altogether unexpected, instead of concern for Gerard or anger at Father Leunig, he was concerned for the family name, for his position as pillar of the church. His mother admitted she had observed some changes but instead felt the priest needed her prayers.

Many people chose not to know what was happening – turned a blind eye. It was uncomfortable to acknowledge that abuse was taking place. I found reading the descriptions of sexual abuse difficult, I wanted to stop reading as it was deeply distressing to read about an adult, a person in authority and held in high regard could subject a child to such abuse. I forced myself to read those chapters that detailed the sexual abuse because far too many turned away and did not want to know. The adult world failed Gerard, but the institution of the Catholic Church crushed and sacrificed Gerard and many like him.

In reading the memoir, I was forcefully reminded that what had happened to Gerard was not only sexual and emotional abuse – and I say this without diminishing the enormity of what happened, but also spiritual abuse. Gerard was forced down and brutalised by a representative of God on this earth. It is full and all-inclusive violation of the entire being of a child.

Gerard was angry – raging against an institution that allowed this to happen to him, that captured his parents but above all refused to acknowledge his abuse, silenced his voice.

They had not perceived the rage that was burning. Gerard was not going to give up now. With the support of his wife, children, psychiatrist and lawyers, he battled the Catholic Church till he got wanted he wanted. 60 years later Gerard extracts compensation and acknowledgement from the Catholic Church.

I don’t think any of us can comprehend the heartbreak and toil that underpins the writing of Anatomy of a Secret. Gerard’s writing is remarkable, his recall, sense of place, internal battle – despite all of this he has written a book that many of us will be able to connect with because of the human experience. This is a book that requires you to stay with Gerard – his emotions, his pain, his anguish, his grief, his battle and his triumphs.

At the very least, Gerard’s story should offer some solace to others who have suffered and continue to suffer similar fates. It tells others that they are not alone, although Gerard was very much alone. It is also transformational for the reader – enabling us to remember our shared humanity and to recollect the ease with which power can be abused and reminding us that we must not be bystanders.

In the course of this meticulous, detailed narrative, we can see how a story that looks extraordinary is all more extraordinary when an individual overcomes the relentless demand for “silence”. Silence at all costs for the gain of others. The memoir shows with bright clarity how the trauma flowed through every part of Gerard’s life, how he learned to live with the secrets. No matter the milestones of success that Gerard achieved, the abuse he experienced is so searing, that it became the formative experience of his life.

I am still aching from the powerful punch of this memoir. Written with compassion, grace and honesty about how cruelty and abuse affect the day to day living of the next day and the next day by a child, an adolescent and an adult – as a son, as a brother, as a husband, as a father and a grandfather. Anatomy of a Secret evokes not only my admiration, but my rage at institutional silence and institutional abuse.

While Anatomy of a Secret is about one person – Gerard, it widens into a reckoning about power dynamics, the nuances of abuse and the contours of self-loathing. The power of Anatomy of a Secret is cumulative: page after page, they build into a larger interrogation of power, faith and family. It speaks of the redemptive power of love – Louise asking that Gerard seek the source of his grief and the redemptive power of speaking.

Tonight is a celebration, a celebration, a celebration of the power of the written word beautifully and powerfully executed by Gerard, a celebration that he is alive and here to tell his story.

Congratulations to everyone involved in the publication of this remarkable book.

It is my absolute honour to launch Anatomy of a Secret with deep respect, admiration and love.

You can buy ANATOMY of a SECRET – ONE MAN’S SEARCH for JUSTICE at a good bookstore near you or online from Fremantle Press.

You can also hear Gerard McCann in conversation with our Editor, Michael Barker, in this compelling podcast interview recorded just after Gerard’s book was short-listed for the Hungerford.

By Michael Barker, Editor, Fremantle Shipping News

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

* If you’d like to COMMENT on this or any of our stories, don’t hesitate to email our Editor.

** WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

*** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!