The telling of this story would not have been possible without the input of Ian “Forrie” Forrest, as it was he and I who, in September 1979, departed for Canberra for a 3-month training program to become dog handlers and kick off Customs’ DDU – or Detector Dog Unit – as it was then known in WA.

The DDU in Canberra comprised of the late Ian Foster as officer in charge with John Stewart and John Flanagan as instructors.

Forrie and I went to Canberra prior to the course commencing to assist with the daily care and exercising of the dogs who, at this stage, were housed at the Red Hill dog pound in a separate area from the general population.

From memory there were approximately 12 dogs who had been selected for the course and each one was walked daily from the pound down to Mugga Way and back. More exercise for the handlers than the dogs, in truth, but at least they got away from the pound for a short while!

It’s worth mentioning that, at this stage in the development of the DDU program, all dogs were sourced from dog pounds or came from families who, for whatever reason, gave up their dog.

All dogs selected for training had to show certain attributes and were mostly large breed German Shepherds displaying an outgoing personality with a willingness bordering on zealousness to retrieve. Couple this with possessiveness and you had the basics for a working dog. Having said this, not all dogs who started on the training continued to display these attributes during training and were subsequently returned to the pound. Had they realised their lack of endeavour would likely cost them their working lives with Customs, I’m sure all of them would have come through with flying colours!

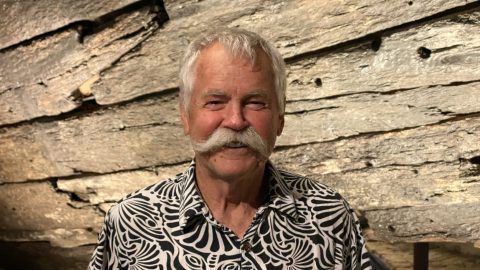

Forrie and Ross with Annie and Marcus

There were, from memory, two handlers each from WA and Queensland and one each from Victoria and South Australia, with each handler commencing the training with two dogs.

A dog’s nose possesses up to 300 million olfactory receptors while a human’s has around six million. On top of that, the area of the dog’s brain used to analyse smells is said to be about 40 times greater than that of the human’s.

In putting this great sense of smell towards detecting narcotics there had to be a motivator for the dog and, in our case, that motivating desire to work came from the challenge of locating the drug coupled with a game of tug of war and enthusiastic praise from the handler.

Anyone who has seen the dogs work will remember the handlers use of a thrower. This is simply a terry towelling cloth wrapped up like a newspaper. So, initially they were thrown away from the dogs so they could see them land. This progressed to throwing them out of sight with the thrower now carrying the scent of whatever it was you wanted the dog to find – which was initially cannabis because it’s a strong smell and eventually was a heroin/cocaine smell which was not as pungent.

Having found the thrower and brought it back to the handler a tug of war between handler and dog then followed coupled with praise for the dog. This tug of war game and praise reward was pretty well the sole reason for the dog wanting to work.

We were often asked if the dogs were given drugs as a reward to develop a dependency. Well, the answer to that is, definitely not! I’m sure that if more thought had gone into the question, then it probably wouldn’t have been asked. Many of the dogs had a long working life, something that a drug dependency wouldn’t have allowed.

In training the dogs, they were encouraged to show an aggressive response to the source of the scent so when the thrower was placed within, say, a suitcase or a wall cavity, the dogs would frantically paw the area thus alerting the handler to its contents. Whilst this worked well in these scenarios it didn’t work for personal concealment of a substance where a passive response was required.

This basic method, to my knowledge, remains the same today and can be applied for pretty well whatever item you want the dog to find given that they all carry their own individual scent. The training from that point on became progressively harder.

As mentioned, each handler started with two dogs and towards the end of the 3 months the better of the two was selected to go on.

Marcus and Annie

So, after three months Forrie and I returned to Fremantle with Annie and Marcus ready to commence work. The dogs were kennelled at what was then the Bicton Quarantine Station in a segregated area. (This no longer exists and has become Bicton Quarantine Park.)

We commenced working the dogs in areas such as Perth International Terminal (now the domestic terminal), Fremantle Passenger Terminal, and Parcels Post located in Perth. At the time, I was confident we would have our first “find” fairly quickly, but this turned out not to be the case. Rather, it was more than 12 months before we had our first “hit”.

Each day we worked the dogs also involved preparing training exercises to maintain their proficiency. In trying to replicate examples of where the dogs could find drugs, for example, in suitcases, letters, parcels etc, required Forrie and me to be on the constant scrounge, particularly for old suitcases. We became regular customers of many an Op Shop.

To maintain the dog’s proficiency required that each training exercise carry only the one constant smell – that being the drug in question. As an example of the problems we faced on a particular training run put together by our Canberra trainers, both dogs completed successfully (we thought) a find on a vehicle. This was not the case, however, and what the dogs had alerted us to was washing powder which we’d earlier used in cleaning the drug bags used to hide the drug. This was a useful lesson as all material from then on was washed in water alone. So, in many areas we learnt lessons by mistake and the dogs and handlers progressed from there.

We developed a good working relationship with the State Drug squad and were used on many of their warrants. On one particular job in the Pilbara, as I recall, Marcus was working inside a house whilst the owner’s dog was under the house wanting to get to Marcus. For anyone who knew Marcus he never shied away from a fight so to say he was distracted from the job at hand was an understatement.

Marcus waiting to board a Customs Nomad Aircraft

Another, more humorous moment came when we were alerted by the Qantas baggage handlers to a large smelly deposit on top of a suitcase going around on the baggage belt. Luckily the suitcase was “made good” and returned to the belt before the owner claimed it.

Examining luggage at the Fremantle Passenger terminal was always an exciting time, more so because it was done in full view of the passengers and general public waiting to meet their friends. Whenever a dog alerted us to a suitcase (remember, aggressive response) it was met with applause and cheers as the dog continued to destroy the suitcase!

As mentioned, our dogs came from pounds and homes where owners no longer wanted them, so it was our job to assess their suitability. I recall occasions going to a home to assess a dog only to be met by a ferocious ill-disciplined mutt happy to bite your hand or whatever other body part was handy.

Having started with the DDU in late 1979, by 1981 my enthusiasm was diminishing so I left to go back to Customs work in PAX Processing. However, Forrie went on the complete 20 years and to implement and oversee many changes to the DDU within WA.

* For more Customs adventures catch up on Michael Metcalf’s marvellous adventures here and Bernie Webb’s wonderful tales here.

While you’re here –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!