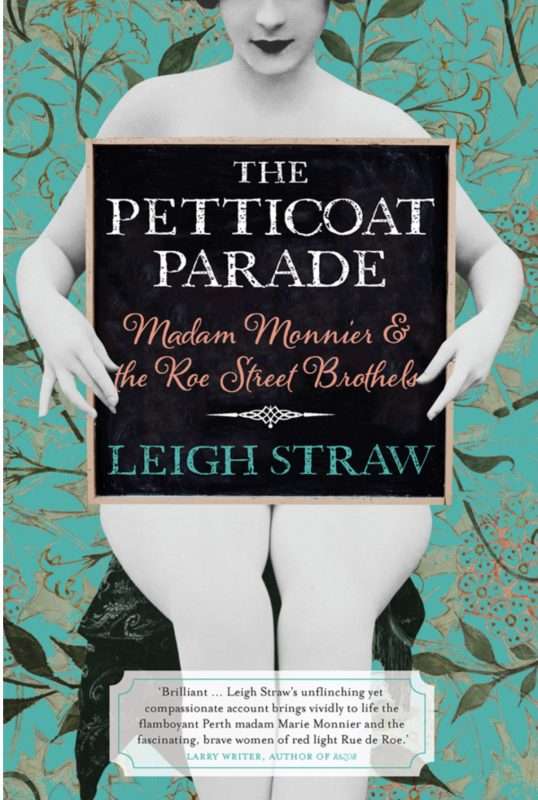

This history of the Perth brothels in Roe Street in the first half the 20th century, The Petticoat Parade, written and researched by Leigh Straw of Notre Dame University, and recently published by Fremantle Press, looked like a challenging read to this reviewer who was initially put off by the suggestiveness inherent in the cover and title. Basically, I agreed with the splendid Eleanor, daughter of Karl, who in the recently-shown film Miss Marx declared resonantly that by now nobody would be earning a living in this trade, because all women would be liberated and earning a good income. Well, let’s just say I had to quickly rethink that perspective even for this early period when many women did have limited choices to earn a living wage.

Reasons for working in the sex trade have, in fact, always been complex. As the British historian and author of Harlots, Whores and Hackabouts expresses it, sex work is not always exploitative and not always empowering: that opposition does not work: “there are sex workers who love their job, there are sex workers who hate their job, there are sex workers who think ‘oh okay I’ll go to work’, there are sex workers who are there because they don’t have enough money, there are sex workers there who are feeding a drug habit, there are people who are being coerced into it, all of these experiences exist within it.” (History Extra podcast, 23/11/21). I found this way of looking at the issue very helpful in reading the Roe Street brothel history which pits the lingering 19th century morality of the era against the actual life of a brothel keeper described as a successful business woman.

Prostitution is still alive and well, of course, both in Fremantle and across the metropolitan area, and due to the much- investigated murder of brothel keeper Shirley Finn in the 70s, we are likely to link police and political corruption to the sex trade. World-wide we are also well aware of a sex slave industry that feeds off the desperation of the disenfranchised such as refugees, and which can include the kidnapping and selling of children.

We do not shrug off these manifestations of the sex trade by smugly referring to the oldest profession (midwifery is probably the oldest apparently), rather we tend to get upset and irate, sign petitions and call for more astute police work. Well, some fast pedalling back into a different era is necessary to enter the early 20th century life of the Roe Street brothels although as I suggest below, some dark corners inevitably will remain.

The author states that her book is not “a moral story about the women who run the brothels, the workers who offered sexual services or the men who paid for it. It accounts for the brothels as businesses.” Just as an aside here, I did not see in the book a comparison between the average incomes earnt in the sex trade as compared to other kinds of women’s work, that would have been useful, though perhaps difficult to obtain.

Madame Marie Monnier, an alias, (who came from France via Kalgoorlie) was a key figure in the first segregated brothel district in Perth in 1912 (population of Perth then approx. 87,000). The district was a development which provided better protection and safer conditions than were available to the women working on the street.

This history is a very important story to tell because such semi-hidden parts of WA history can tell a much more nuanced story of Perth than more mainstream topics. There is, for example, careful discussion of the stereotyping of the Chinese and the reality of opium dens; as well as the importance of selling sly grog – and sometimes heroin – in the brothels, and the misplaced emphasis in the period on the sex trade and venereal disease.

Violent men, particularly traumatised and often drunk veterans were a concern for women after WW1. In 1919, after being turned away from a brothel, one soldier returns in fury sometime later with a gun, randomly shooting through the front door’s peephole and missing Monnier’s eye for, after using the peephole to see what the noise was, she had moved herself and her workers only seconds before, and was merely shot in the arm. Court records provide evidence of a woman who may have been using a brothel as a refuge, working as a domestic there for three months, to hide from a violent husband.

As the history of a woman in charge in the sex trade business in this period, it is, for the most part, a positive story. Apparently Monnier sent for her friends from France to work with her and they return to France on occasion for holidays (a very long holiday?). She sends the workers on retreats in the Perth Hills, insists on checking her customers for cleanliness (could be fraught sometimes, I imagine?) and is mostly tolerated by the police within the Roe Street containment area and she is almost celebrated by various Perth papers.

But darker issues do lurk in the book which, due to the paucity of the historical record, cannot be elaborated. It is stated for example that indecent assault on a child under 16 was a common charge against men prior to WW1 (it is unclear why this would change later). In one brothel a 21 year old woman was asked to wear pigtails to look like a 15 year old: “ ‘cause men are villains you know.”

It was illegal to allow anyone under 21 to work in a brothel, but there are references throughout to teenage girls, some as young as 14, working as prostitutes (on the street and in the brothels). There is evidence of women’s young families living in the brothels, while being kept separate. One woman is mentioned as working in a brothel alongside her daughters.

Child abuse itself was clearly an issue of general concern to the police and the first policewomen in WA in 1919 were tasked with ensuring “the madams were held to account for the ages, health and welfare of their workers” and with “keep[ing] young children from the streets, more especially at night.” This of course would have included young boys on the street though not specifically mentioned. The policewomen watched newspapers and persons for those “who may decoy young girls by advertisement” and who “decoyed and drugged” young people directly.

Leigh is to be applauded for this vivid and interesting account of this period (which also makes mention of the Fremantle brothels in the West End).

I think Leigh would stress that the police concerns, regarding young women overall, were likely unduly informed by lingering 19th century fears rather than by absolute reality. And of course, as said earlier, there would have been many different women with many different experiences.

But our current knowledge of under-age child exploitation is harder to shake and inevitably lurks in this history. It is perhaps safer to say therefore that when it came to the exploitation and coercion of children we do not actually know its extent.

A very interesting history and a worthwhile read.

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

* By Christine Owen