Now, we are not saying that just because Iain Grandage has Freo connections and Nikolai R-K is a dead, pre-revolutionary Russian.

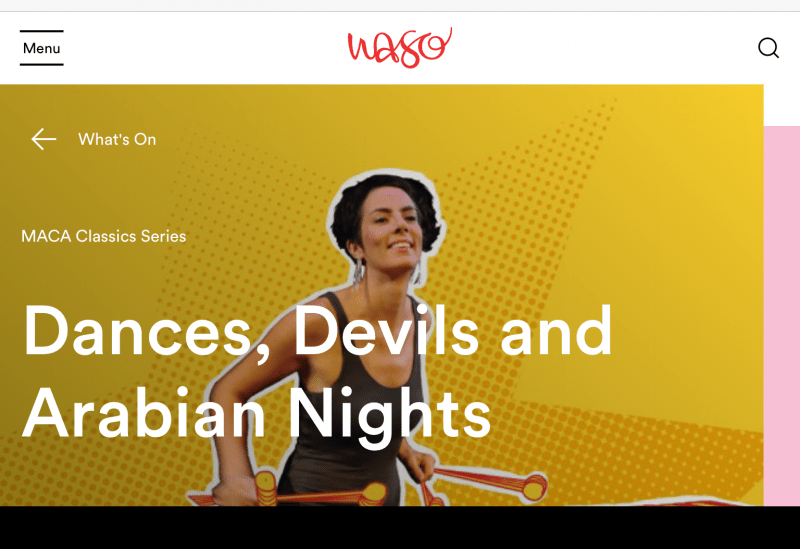

We’re saying it because last night, at the Perth Concert Hall, the WASO performance of Grandage’s percussion concerto, Dances with Devils, with Claire Edwardes the solo thumping, tinkling and persuading percussionist, under the deft baton of conductor Benjamin Northey, was dazzling – and we thought we should share!

Look, WASO’s performance of Rimsky-Korsakov’s famous 1888 symphonic suite, Scheherazade, was quite exquisite and, at times, utterly powerful – as you’d expect of the WASO. There were mighty sequences where the trumpets and whole brass section, fortified by the oboe and rest of the woodwind, not to mention the percussion and strings, made you want to stand and march and exult over the Sultana Scheherazade’s power to talk down the Sultan Shariya’s plan to slay all his wives.

And even more than that, the moments when the strings, especially the solo violin of Laurence Jackson and the harp of Yi-Yun Loei, simply entranced you, and transported you to a thousand and one Arabian nights.

Credit ABC

But it was Grandage’s percussion concerto, in four movements, and Edwardes’ performance of it that stole the night.

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

Because the audience were there for the main Nik R-K suite after the interval, and did not arrive humming Grandage (if that were possible), the concerto was as exciting – yes, that’s the word – as it was unexpected.

The concerto is a work that the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra commissioned of the composer especially to be played by the percussionist, Claire Edwardes. It had its world premiere in Melbourne in 2017, and since 2017 hasn’t been performed again. This was its homecoming, so to speak, in Grandage’s hometown.

Credit ABC

This tells, for you can’t imagine any old percussionist performing such a work with the flair, finesse and passion that Edwardes displays, without the composer and the soloist being in perfect sync.

No doubt composers compose all sorts of works with a mythically talented artist in mind to show off the work to it greatest effect, but here the combination of artist and composer is something else, as Iain Grandage acknowledged in his short address to the audience immediately before Edwardes’ performance.

Grandage also explained that the work was inspired by The Australian Bush, that great mythic landscape that has always held a particular grasp on the psyche of white Australians. The musical story that unfolds is not always a happy one, especially in the second movement where suicide by drowning is the plot piece.

The front of stage held all the percussion instruments. On one side were the marimba, drums and tambourines, temple blocks and a few cymbals. On the other, something that can best be described as a contraption, made just for the second movement, that looked like something between a gallows and a reformer Pilates machine, to which Edwardes was effectively strapped. Not quite what you’re thinking, but very unusual just the same. Through Star Trek like devices attached to her arms, Edwardes could control and vary tubular sounds with water. Which is what she then did.

The percussion sounds, their grandeur, their pathos at times, and their pure power and simple delicacy at other times made the concerto a rare experience, an experience a long way from late 19th century Russia. An experience to remember. Thank goodness for contemporary art, contemporary composers, and contemporary performers!