Shipping News readers have the opportunity to journey with the Hougoumont, the last convict ship to Australia which arrived in Fremantle on 10 January 1868.

On board were 62 Irish Fenian political prisoners as part of a total of 280 convicts. The 150 year anniversary of this event will be commemorated from 5 – 14 January 2018 at the Fenians Fremantle and Freedom Festival. There will also be an Exhibition of Transportation at the Fremantle Prison from 9 January 2018.

Casey’s Diary

The Hougoumont rounded the Cape of Good Hope on 12/12/1867, so the Fenians are now on the last stretch of their voyage to Fremantle.

Our hero from the last log, John Sarsfield Casey has finally been taken off the hospital diet, on which he had been half starved. He writes …

Saturday, 7 December 1867

The morning was cloudy, raining at intervals, coming in fitful gusts. The sea was very rough, and it was extremely cold both day and night. Passengers were on the lookout for the Flying Dutchman and I was amused to see the look of terror depicted on their countenances at the idea of meeting him.

Then the day took on a strange ominous aspect. Everything became still. The sky was of a dull grey leaden hue. No clouds could be seen, but the vault of heaven was wrapped in one dark impenetrable veil, whose dreariness was increased by reflections on the water beneath. The surface of the ocean was glossy, and not a breath of air disturbed the solemn eerie stillness.

At midday the rain poured down in torrents, and this continued for about three hours, incredibly heavy rain, yet the sea remained flat calm, the air cold and thick and still. When the rain ceased, all was silent as the grave. Ignorant of impending danger, the prisoners sat down to their customary amusements, interrupted only by an occasionally expressed wish for a breeze to spring up.

At 6 o’clock in the evening, the sails were shortened and everything, both on deck and aloft, was made ready for a wild night. An hour later the ship was sailing under closely reefed topsails, when John Flood first noticed that the hatchways were being nailed down.

At 8 o’clock we retired to rest but scarcely had two hours elapsed before a dull roaring sound was heard in the distance. It grew louder and louder until it seemed to burst over the ship. In a few minutes, the sea was lashed into a fury and the ship speed through on a gale of terrific violence.

Sleep was out of the question. The noise on deck, waves dashing against the side of the vessel or bursting over the gunwale. The wind thundered through the rigging, and banished all thoughts of rest from the panic-stricken minds of those beneath the nailed down hatchways.

During the height of the storm, not a glimpse was caught of the dreaded ‘Flying Dutchman’. John Boyle O’Reilly penned a few lighted-hearted lines in honour of the occasion…

We’ve rounded the Cape and we’ve caught not a sight

Of the Dutchman, his ship or his crew man

All the sailors believe in the ghostly old wight

And they’ll tell you the story is true man.

They say that he lives in the seas at the Cape

And about him they’ll talk very much man,

But howe’er it may be, we’d a lucky escape

From the ghost of the old Flying Dutchman.

Despite the uncomfortable days leading up to and including Saturday 7 December, the 5th issue of The Wild Goose made its appearance on schedule.

The Wild Goose

Let’s take a closer look at this this very interesting newspaper written on board the Hougoumont. Fremantle readers will have the privilege of seeing this original document, which will be on display at the Fremantle Prison as part of their Exhibition of Transportation which opens on 9 January 2018.

Other readers can view the document in digital form by searching on line for the Flood Papers in the archives of the State Library of NSW: www.sl.nsw.gov.au.

Scholar, L M Rutherford from University of New England tells us:

The manuscript journal, produced with such flair on ‘the high Seas’ by a group of Fenian political prisoners, is an item of interest for both Australian and Irish historians as well as bibliographers. In its conscious conformation to the design and layout of printed journals of its day and its literary and political focus, it constitutes a unique moment in the history of Church, State and books.

How did it come about?

In his obituary for O’Reilly, Denis Cashman records that aboard the Hougoumont there was a scheme, eagerly endorsed by O’Reilly, to capture the ship. Presumably this was discussed towards the end of October, when a change of direction could have brought the ship to the United States without too much trouble. The Fenians with shorter sentences or with families left behind may have rejected the consequences of permanent exile, or they may have been deterred by the logistics of controlling both the ship’s authorities and more than 200 criminal convicts. In any case, the plan was not pursued, and by the beginning of November, a new project was at hand to boost morale.

Meetings were held to organize the production of a regular newspaper: The Wild Goose: Or A Collection of Ocean Waifs. John Flood was to be the editor, O’Reilly the sub-editor and John Edward Kelly was appointed manager.

John Flood, born 1835, was the son of a Dublin ship-owning family and one of the oldest of the transported Fenians. He had an intimate knowledge of his father’s shipping trade, and considerable navigational skill. As a boy he’d attended the elite Catholic College of Clongowes Wood in Dublin and was a scholar. He became a lawyer’s clerk and studied law under the eminent Irish lawyer Isaac Butt, before joining the Fenians in the early 1860’s. He’d earned his nickname ‘the Navigator’ for his success in getting the Fenian leader James Stephens out of Ireland in a small boat.

Edward Kelly was an Irish-American formerly of Kinsale, County Cork, and one of the two Protestant Fenians among the Hougoumont contingent. It was Kelly who suggested the journal’s title. The ‘Wild Geese’, referred to the exiled Irish soldiers of a former conflict who took service in the French and foreign armies following the collapse of ‘their country’s struggle for liberty.’

Publication was made possible by Father Delany, the Catholic chaplain, who provided paper, pens and ink and was himself a contributor to some of the later issues.

Style

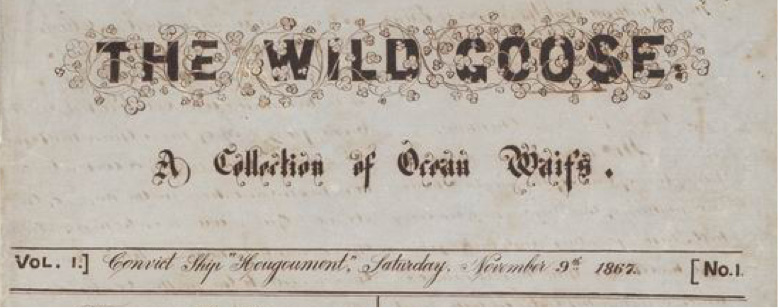

The Wild Goose is a hand-written manuscript, for the obvious reason that there was no printing press on board the Hougoumont. In design and layout, it deliberately imitated a printed journal of its day.

The first issue was produced on Saturday, 7 November 1867. It was made up of four sheets, eight pages of double-column layout. The paper was foolscap, unlined, though in later issues, where the paper quality was better, one can still see the fine ruled pencil lines used for guiding the writing.

The titles were the work of Denis Cashman. The main title, ‘The Wild Goose’, is centred, in heavily inked blocked capitals surrounded by a fine-filigree of tiny shamrocks: ‘a wreath of shamrocks with the name peeping thro it’ is Cashman’s own description.

The Wild Goose – A Collection of Ocean Waifs

The sub-title, ‘A Collection of Ocean Waifs’, is in a decorated gothic.

Underneath this comes the main body of the text, in two columns. Caption titles are usually in a copperplate hand, while the running head throughout, ‘The Wild Goose’, is in heavily-inked italic capitals. There are at least two hands apparent in the main body of the text of the paper.

If more than one copy of each issue was made – and we have virtually no evidence about how many copies were able to be produced – no doubt the copying for each section was shared about.

Contents

The first issue opened with an address by John Flood, headed ‘To Our Readers’, where The Wild Goose personified explained its objects and aims. Cashman’s opinion was that it was ‘beautifully done’.

This was followed by the first instalment of a serialized tale by Thomas Duggan,

‘Queen Cliodhna and the Flower of Erin: A Tale of our Pagan Ancestors‘.

This is followed by a section headed ‘The Markets’, which consists primarily of a witty disparagement of the ship’s food:

‘Pork rather higher than usual, and still advancing. – Biscuit getting livelier. Chocolate a drug in the market. – Tea rather flat. – Oatmeal steady.’

Self-conscious reference is made to the normal demands of print-house operation, composition and the demands of production and layout. For example, in the snippet of text at the foot of the second column of page 3 (Number 1):

‘Our entire staff, “devil” and all, have been fairly driven to their wits ends to concoct something to fill up this little corner, and have utterly failed.’

Reference is made to the shortage of paper and writing implements, usually in the ‘notes’ and humorous ‘want ads’ in the final column of each issue – for example:

‘Wanted, by the Editor, several reams of foolscap, together with a corresponding quantity of black ink and steel pens, for which goose quills will be exchanged‘ and

‘Wanted, A few black lead pencils that were originally made to write, not to sell’.

In total, seven weekly issues of The Wild Goose were produced, the last being a double-sized Christmas edition. The organization of the journal is constant throughout the run: an opening address, followed by a fiction section, followed by the news section and ‘Answers to Correspondents’, maintaining the humorous punning style.

The authorities and the plight of the convicts came in for mild ridicule in this latter section. However, the attitude taken by the English Captain and crew was tolerant, for example:

‘Curious wants to know why the upper deck is so constantly flooded. How can it be otherwise with SWELLS (from Aft) continually dashing along it’

‘Answers to Correspondents’ was followed by articles, usually of a philosophical nature, such as ‘Home Thoughts’ written by Flood, with contributions by Father Delany.

Next followed the poetry section, with an ornate decorative title. O’Reilly provided nine poems in all, including this one written for Denis Cashman…

As you battle your way through the world

And measure your own, with its might,

In its face let your gauntlet be hurdled,

And boldly press on to the fight.

Let no failure your energies smother.

Unawed, with adversity cope.

Let your motto be ‘Honour’, my brother,

Your watchword and war-cry be ‘Hope’.

On the right of your course, be reliant,

And onward unswervingly steer.

Rise o’er worldly censures, defiant,

Condemning the frown and the sneer.

And, though bitter the draught of the trial,

On brother, and quaff it with pride.

Though you drink to the dregs of the vial,

Still cherish the truth for your guide.

Let not frowning Misfortune appal you,

Nor shrink ‘neath Calamity’s rod.

Remember; whatever befalls you

Is willed by an all-seeing God.

Act yourself, and ne’er trust to another.

When duty awaits, never rest.

Look onward and upward, my brother,

And forget not, what is, is the best.

After the poetry came a section which might best be described as ‘Irish Interest’, either a personal memoir from one of the Fenians or an Irish travelogue. The first number contained a piece by Joseph Noonan, entitled ‘A Leap for Liberty’, which detailed his arrest in Kerry following the March rising and his subsequent train journey and escape. Each edition closed with a ‘Notes and Correspondence’ section.

Page 3 contained a ‘News’ column. Clearly little fresh news was available to the ship-bound population, so the Fenians composed their news section of mock-Olympian nonsense about the doings of the Gods of ‘Earth, Sky and Sea’.

This section is verbally embellished with the characteristic Wild Goose extravaganza of bad puns: for example

‘Marine Regions: Nov.9~. – Squall’s ahead. Neptune thinks he has enough of finny uns in his dominions, and is incensed at the thought of a fresh influx of those turbulent beings.’

In answer to question from “Enquirer” the editor responds…

’Very little is known of the first settlers of Central Africa; but the supposition that it was colonised by the Irish Chieftain, Tim Buctoo, appears to us to be a popular error’

Copy would seem to have been composed on slates, owing to the scarcity of paper, and then transcribed for publication. Humorous reference to the ephemeral nature of such copy can be found in the journal; for example, Issue No.11 laments that

‘A great quantity of our manuscript has been obliterated, some careless person having sat on our slates. We have thus lost much interesting and valuable matter, for which mishap we intend to stop the grog of our “devil,” which, we hope, will be satisfactory to the public.‘

And a later number announces:

‘Any person found trespassing on the editor’s slates, or in his offices will be prosecuted.‘

Ink and paper quality vary. Sometimes the ink becomes quite thin, as if it were being watered down to increase the amount which could be written.

Numbers 1-3 are produced on wove paper. Issues 4-7 utilize a finer quality laid paper. English Shipboard authorities seem to have encouraged and facilitated the production of the paper.

The Christmas special impressed the Captain and his mates to such a degree that extra copies were requested by them, and the staff readily complied. In return for their industry, which was no doubt viewed as a pacifying occupation, the editors were granted extra rations, tobacco, and privileges.

They were permitted to remain on deck until 7.30 p.m., and O’Reilly was permitted to move out of the main convict hold to join his fellows in Number 6 Mess.

It is difficult to know how many copies of individual issues were produced. Certainly, because of the labour involved and the shortage of paper, there cannot have been many.

What effect did the Wild Goose have on the Fenians?

Writing and producing the newspaper, brought the men together and kept up their spirits. In his diary, Denis Cashman wrote of his work on the paper:

‘This occupation pleases me very much – it passes the time and takes me from my thoughts which at times are rather gloomy’.

And in a dedication to a poem written for his friend John Flood, O’Reilly spoke openly of the cementing of affection between the Fenians involved in the journalistic enterprise:

‘Hereafter, when our exile is ended [these lines] may recall to memory, the beginning of our friendship, and the many pleasant (and busy!) days we spent together over our little “Wild Goose”.’!

As O’Reilly describes it, at the start of the journey, they were particularly apprehensive about their incarceration amid a violent and unrestrained criminal population:

As I stood in that hatchway, looking at the wretches glaring out, I realized more than ever before the terrible truth that a convict ship is a floating hell. The forward hold was dark, save the yellow light of a few ship’s lamps. There were 320 criminal convicts in there, and the sickening though that occurred to us, are our friends in there among them? There swelled up a hideous diapason from that crowd of wretches; the usual prison restraint was removed, and the reaction was at its fiercest pitch. Such a din of diabolical sounds no man ever heard. We hesitated before entering the low-barred door to the hold, unwilling to plunge into the seething den. As we stood thus, a tall gaunt man pushed his way through the criminal crowd to the door. He stood within, and, stretching out his arms, said: ‘Come, we are waiting for you’. I did not know the face; I knew the voice. It was my old friend and comrade, Keating.’ (Roche)

Other Fenians closely associated with the project included Cornelius O’Mahony, former secretary to the IRB leader James Stephens and organizer of the movement’s newspaper, the Irish People; Thomas Duggan, a National School teacher from Ballincollig, County Cork; John Sarsfield Casey, Mitchelstown, County Cork; Denis Cashman, a former clerk, and ‘centre’ of the Fenian circle at Waterford; Michael Cody, the ‘centre’ from Callan, County Kilkenny; Joseph Noonan from Killarney, County Kerry; and Eugene Lombard, from Cork City.

Lombard, who acted as ‘copyist’ or ‘copy-boy’, wrote home to his parents that publication of the journal had been ‘the greatest joy and relaxation of the 62 Fenians on board the Ship.’

Saturday was publication day at the ‘Printing Office’, which, as the colophon* to the first issue announces, was at No 6 Mess, in the Civilian Fenian Quarters:

‘Printed and published, at the Office, No 6 Mess, Intermediate Cabin, Ship “Hougoumont”, for the editors, Messrs John Flood and J.B. O’ReiIIy, by J.E.K. (Kelly) Registered for transmission abroad.‘

On publication day the paper would be read below decks to the Fenians, maintaining the element of performance which was not, of course, unusual in the history of the consumption of news journals.

The last issue was produced on 21 December 1867.

On 10 January, the convicts disembarked at Fremantle Wharf, and embarked on a new penal existence. John Flood held the only complete run of The Wild Goose. This was held to be his own property and was kept for him until his release. On gaining his freedom, Flood settled in Gympie, Queensland.

Following his death in 1909, the manuscript passed to his daughter, and then to a grand-daughter, who deposited it in the Mitchell Library in 1968: one hundred years after the arrival of the Fenians in Western Australia.

Note from Margo O’Byrne:

John Flood is buried in Gympie, Queensland. That’s the town where I lived for five years and went to boarding school, attending mass in the same church where John Flood had knelt years earlier. As teenagers, we were fascinated by the large Celtic cross in the local cemetery, which was made of green granite and clearly belonged to an important Irishman, (let’s face it, there was not much going on in country towns in those days). I could not have known then that I would come to live in Fremantle and have an ongoing connection with this man and his story?

*In publishing, a colophon is a brief statement containing information about the publication of a book such as the place of publication, the publisher, and the date of publication.

Ref:

Waters, Ormonde D.P. The Fenian Wild Geese, Catalpa Publications, 2011

Rutherford, L.M., in Bibliographical Society of Australia and NZ Bulletin, Volume Sixteen, Number One, May 1992