Snook Crescent curves around the centre of the garden suburb of Hilton. The street’s name is a reminder of Fremantle’s violent past, now incongruously juxtaposed with the tranquil scene created by tall trees and flocks of noisy birds.

John Snook was a respected member of the Fremantle community, whose death in 1887 resulted from a gunshot wound received at the recently opened Fremantle Town Hall. As reported in The West Australian at the time, this was “another of those dastardly shooting outrages, for which in the last few months the Port has acquired so unenviable a notoriety”.

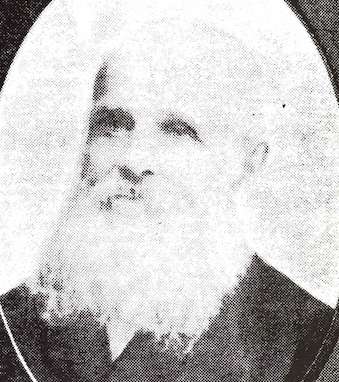

Councillor John Snook, ca 1887. City of Fremantle

A photo of Mr Snook from the time shows a balding man with a white moustache and longish beard. About 70 years of age, he had recently retired from Carter & Bartram, a general store in William Street, Fremantle, where he had been employed since his arrival from England in 1853.

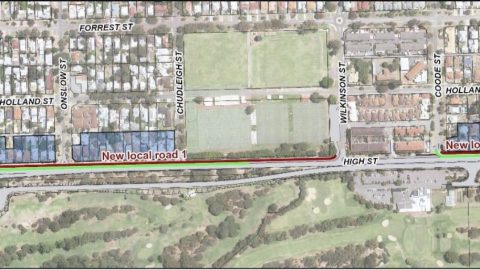

Brockhoff’s store is believed to be where the business of Carter & Bartram was carried on from 1852, courtesy Freotopia

Through Snook’s efforts the working hours of Fremantle store workers were reduced, with the introduction of early closing times in the evenings and a weekly half-day holiday.

Mr Snook was also active in the local community, serving as a Fremantle Town Councillor, Quartermaster Sergeant to the Fremantle Rifle Volunteers, member of the Fremantle Reform Association (where he was credited with recruiting numbers for the Register of Voters), and member of the Literary Institute, where he organised popular fortnightly concerts during winter.

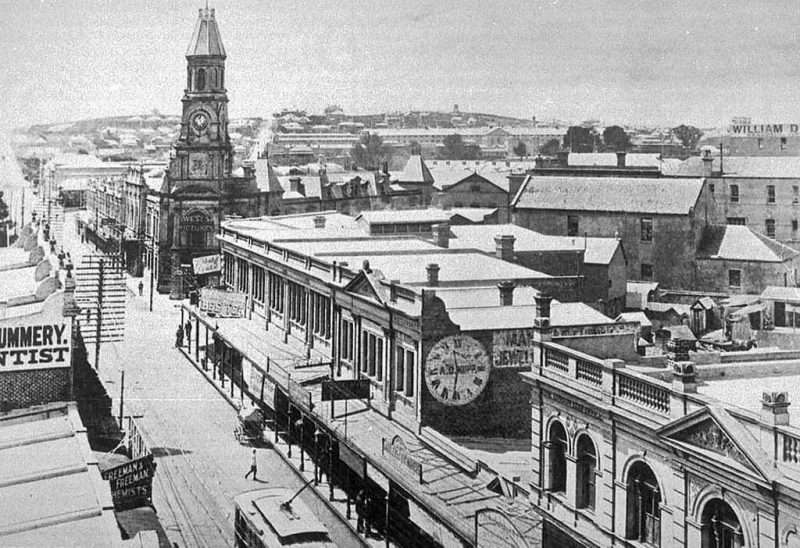

Fremantle, with its new Town Hall, ca 1889

Celebrations of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee were held at the opening of the Fremantle Town Hall on 22 June 1887. The following evening the Town Hall hosted a children’s ball. Snook, along with the Town Supervisor, Edward Gliddon, was acting as steward when around 10pm the two men were approached by a short, round-faced man with a moustache and whiskers. William Conroy, the licensee of the recently opened National Hotel in High Street, demanded to be admitted, despite being told that only women and children were allowed in. Conroy claimed he had been invited by a Mr Hughes and, according to later reports in the The Inquirer and Commercial News, he “persisted in his attempts to force an entrance, but without avail; and eventually he was turned away by the combined efforts of Councillor Snook and the caretaker, greatly to the amusement of the crowd that had assembled in front of the entrance door”.

Shortly before 11.30 pm, the Mayor, Mr Daniel Congdon, spoke with Conroy in the vestibule of the Town Hall near the supper room. Conroy had returned briefly to the National Hotel before heading back to the Town Hall. By this time the children had left and some of the attendees were dancing. At 11.30 pm the Mayor invited the councillors, stewards and their wives to a supper in the reception room. At around 1.30 am the Mayor was proposing a toast, when Conroy came to the door and asked for Councillor Snook. Congdon politely asked him to cease his interruptions, and Conroy complied, waiting outside the room for the party to break up.

Soon after, the Mayor’s son, Sydney Congdon, saw Conroy and Snook at the entrance court near the main door of the Town Hall. The two men, who apparently were distantly related, appeared to be having an amicable conversation, and Sydney Congdon said he heard someone laughing when, without warning, Conroy produced a revolver from his pocket and shot Councillor Snook in the face.

The bullet entered by the mouth, splintering Snook’s lower jaw, before exiting just below his right ear. The bullet was later found in a cloakroom, where it had landed after grazing the corner of the wall. A waiter, Henry Naylor, who also witnessed the scene, took hold of Conroy.

At the sound of the shot the Mayor and a local MLC, Mr WC Pearse, rushed out in time to see Snook falling to the ground, blood gushing from his mouth. “My God, what have you done?” asked Pearse. “He put me out, now I have put him out,” Conroy replied.

The two men took hold of Conroy’s arms and took him to the cloak room, after removing a small pocket revolver from his overcoat pocket, and sent for the police, who took him to the lockup at the Fremantle Roundhouse in handcuffs. To the accompaniment of hysterical shrieks and fainting by some of the guests, another Councillor, Mr Haley, sat Snook upright and attempted to staunch the flow of blood. A doctor was sent for, the wound was dressed, and Councillor Snook was returned to his home.

In the meantime, Sydney Congdon had gone to find the police, who arrived shortly after and arrested Conroy. Corporal Murray, who made the arrest, later told the court that Conroy, who appeared to be sober, had not spoken a word. He remained in police custody for over a month, when he was brought up on remand at the Fremantle Police Court before a magistrate and two justices of the peace. After evidence was heard from several witnesses Conroy was committed to trial at the next sitting of the Supreme Court.

George Walpole Leake

Before the trial could take place, and three months after the shooting, Snook died of his injuries. When Conroy finally appeared before Justice George Walpole Leake and a jury in the Supreme Court a couple of weeks later, Conroy was indicted to answer to the charge that he had “feloniously killed one John Snook by shooting him with a revolver”.

There were several eyewitnesses and Conroy did not deny the charge, although he declared he had no memory of having fired the shot, a claim he never wavered from. The defence, headed by Septimus Burt QC, raised a plea of not guilty on the grounds of insanity. Witnesses mentioned his frequent fits of crying without apparent cause, his frequent pacing during the night with “a wild look about him”, saying he was tired of his life. He had been seen handling a revolver and threatening to use it on himself, and had also fired shots in the dining room and the kitchen of the hotel, breaking glassware and furniture.

Evidence of a family history of insanity was also introduced, including that a great-aunt had died in a lunatic asylum. Conroy’s aunt mentioned that his sister was “not in her right mind”, “restless”, “strange in her manner”, used to walk around all night and often asked for medicine. Conroy had recently arranged to send his sister back to England to enter an asylum.

The Colonial Surgeon of Fremantle, Henry Calvert Barnett, who had served as the Superintendent of the Fremantle Lunatic Asylum for about 15 years, expressed his view as an expert witness that the prisoner was liable to suffer from insanity and homicidal mania, and should therefore not be answerable for his actions.

The Attorney-General, summing up for the prosecution, told the jury that it was a principle of law that every man was presumed to be sane and to possess a sufficient degree of reason to be responsible for his crimes, until the contrary was proved. Since Conroy went about his daily business and conducted his affairs as a publican shrewdly and successfully, his “eccentricities of conduct” should not be accepted as symptoms of insanity.

Justice Leake told the jury it must be proved to their satisfaction that at the time Conroy committed the deed he was incapable of distinguishing right from wrong, and did not know that his act was an offence against the law.

The jury took less than two hours to deliver a verdict of guilty, accompanied with a strong recommendation of mercy. Justice Leake responded that he would lay their recommendation before the Governor at the Executive Council, and proceeded to pass the sentence of death. Conroy was taken in irons to Perth Gaol.

The Governor, Sir Frederick Broome, was on a long tour of the Murchison district, at the time of sentence and the Executive Council was delayed for another month. During this time Conroy’s numerous supporters prepared a petition praying for commutation of his sentence.

Over 1500 citizens, including every member of the jury who had tried him, signed the petition. Nevertheless, on his return to Perth, the Governor, acting on the advice of the Executive Council, decided to allow the law to take its course.

Letters by various doctors, arguing both sides of the case, were published in The West Australian, and a public meeting was held in the Perth Town Hall, attended by around 1000 citizens, at which a resolution urging respite for the condemned man was unanimously adopted. Governor Broome carefully considered the resolution in consultation with two judges and medical practitioners who were personally acquainted with the case, but decided once again that the law should take its course.

Conroy was an exemplary and penitent prisoner, despite maintaining that he remembered nothing between being turned away from the Town Hall and finding himself in custody in the Fremantle Round House. He went cheerfully to his execution by hanging at the Perth Gaol, even assisting the blacksmith to cut off his irons in preparation. Following a recent petition by citizens residing near the gaol, the usual practice of tolling a bell and raising a black flag at executions was not followed, resulting in a rumour that he had been reprieved on the scaffold.

It was an overcast day, and one newspaper reported poetically:

“Gloomy was the morning, and not a single beam of the sun shone forth

To guild with rays so light and free

That dismal, dark frowning gallows-tree”.

Gloomy and dismal indeed! The execution, the very last to take place at the Perth Gaol, was botched. The rope being of insufficient strength to break his neck, Conroy died of strangulation after 15 minutes of kicking, sobbing and gasping at the end of the rope.

Note: The murder, trial and petitions for mercy were extensively covered in the local media of the time and subsequently written about. Here is a selection of sources used for this article.

“Supreme Court – Criminal Side”. The West Australian. Perth: National Library of Australia. 8 October 1887. p. 3. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

“Fremantle’s Town Hall Murder”. The Mirror. Perth: National Library of Australia. 29 May 1937. p. 17. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

“Another Shooting Tragedy at Fremantle”. The West Australian. Perth: National Library of Australia. 25 June 1887. p. 3. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

“Fremantle Shooting Case”. The West Australian. Perth: National Library of Australia. 27 September 1887. p. 3. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

“Conroy’s Sentence Confirmed”. The Daily News. Perth: National Library of Australia. 11 November 1887. p. 3. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

“Execution of William Conroy”. The Inquirer & Commercial News. Perth: National Library of Australia. 23 November 1887. p. 2. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

“Execution of William Conroy”. The Daily News. Perth: National Library of Australia. 18 November 1887. p. 3. Retrieved 30 January 2025.

https://jenealogyscrapbook.com/2018/08/05/52-ancestors-34-family-legend-john-snook-1818-1887/ Retrieved 30 January 2025.

* By Vivien Encel, who claims copyright in this work

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~ If you’d like to COMMENT on this or any of our stories, don’t hesitate to email our Editor.

~ WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

~ Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!

~ AND Shipees, here’s how to ORDER YOUR FSN MERCH. Fabulous Tees with great options now available!