Early in 1962 the American author, James Baldwin, published an article in the New York Times Book Review. Articulating the responsibility of writers not to hide behind their pen and to deal honestly with the world in which they find themselves, Baldwin wrote: ‘Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced’.

Two generations later, in his book, Here Be Monsters, Fremantle-based Richard King uses this quote to underline the snowballing dynamic involving technology, capitalism and human nature and the urgent need to face up to the reality of what is already happening and get clear about what we need to do to restore, revalue, and respect the essence of what it means to be human. Like others who harbour grave misgivings about the future of homo sapiens and the Earth we inhabit, King confronts the big issues head on. His focus, contained in the book’s subtitle, is whether technology is reducing our humanity. Unsurprisingly, he offers plenty of evidence that this is already the case, as he meticulously explores how infatuation with ‘techno-science’ adversely affects our capacity and need for human connection; how treating our bodies as machines and fiddling around with genetic codes dehumanises us; and how creativity and human agency is lost or compromised in a world of algorithmic machines. In short, we morph into flesh and blood versions of our robotic inventions.

Similar prophecies, once the province of science fiction, have reverberated through the years following the scientific – industrial revolution. Writers such as Aldous Huxley in Brave New World and George Orwell in 1984 foretold dystopian futures. Previously, Mary Shelley, somewhat out of character for 19th-century female sensibilities, served up Frankenstein. More recently, the formidable Margaret Atwood gave birth to The Handmaid’s Tale. But not even these imaginative artists could reckon with the speed of computerisation and its rapidly unfolding implications.

Published in 1949, 1984 was Orwell’s final novel. The chief character, Winston Smith, lives in a dingy apartment where the lift is not working. As he climbs the stairs, a large poster stares down at him. Big Brother Is Watching You. The world Orwell envisages is one of fear, alienation, and control. What we would now call disinformation is at its core. In London, the Ministry of Truth, where Winston works is an enormous pyramid with 3000 rooms, decorated with the three slogans of ‘the Party’. War is Peace; Freedom is Slavery and Ignorance is Strength.

I can’t remember when I read 1984 – probably in my 20s, with that date still away in the future. Likewise, Brave New World. But I’m pretty sure I shrugged off the messaging and got on with the business of being a young person. Despite the Cold War, the Capitalist – Communist impasse, the threat of a nuclear implosion, and the horrors of the Vietnam conflict, a slide into dystopia seemed the stuff of fantasy; a dark playground for some novelists and a morbid fascination for readers. Besides, the privileged young folk of my generation were more focused on finding their way in the world and having fun as they did so. In Western Australia, university education was more or less free, jobs were plentiful, and Big Brother surveillance was limited to the local constabulary showing up at closing time in our favourite watering holes. To cream our adventurous cake, Europe offered a quasi-cultural fix before we began or resumed careers, got hitched, and began to produce the next generation. In varying degrees, we were optimistic, ambitious, and secure.

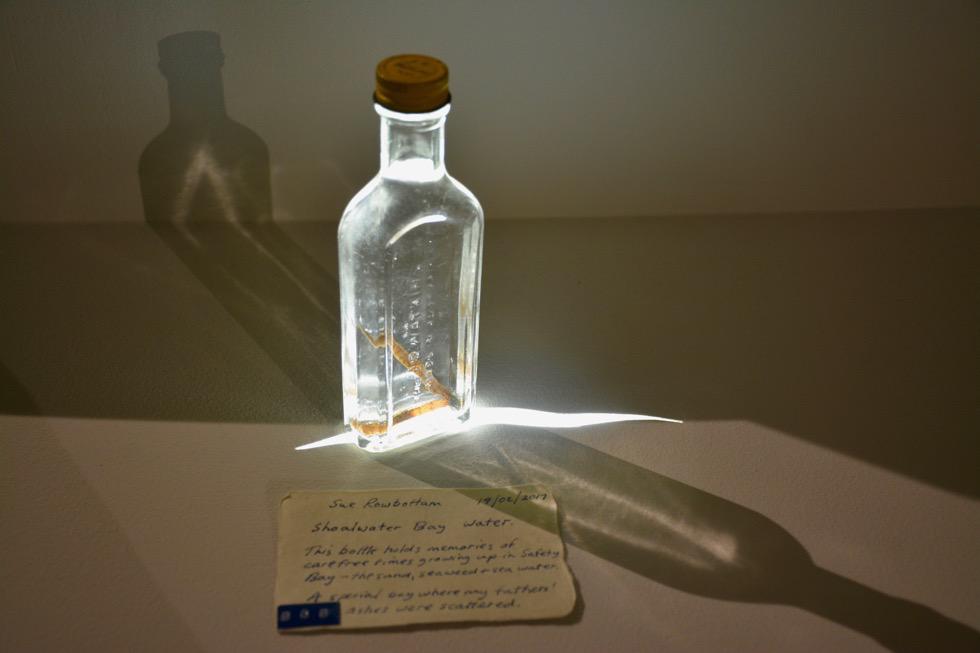

Credit Zyanya Citlalli for Unsplash

Fast forward half a century. Like many others, I am much less sanguine. Idealistic hopes for ‘a better world’ have been drowned under the heavy tide of realism. The human animal, for all its amazing creativity and cleverness, remains rooted in a kind of modus reptilia – where attitudes and actions are bound up in flight, freeze or fight, accentuated by ancient hostilities, rigid ideologies, and ruthless competition over resources. Global harmony, like courageous leadership, hovers in a distant dream cloud, never within reach. When asked about Western civilisation, Mahatma Gandhi reportedly quipped: ‘it’s a good idea’. Nowadays, with an unrelenting global emphasis on consumer-driven growth against a backdrop of polarised societies riven with apathy and zealotry, the word ‘Western’ appears superfluous. At scale (as the economists like to say), civilised we ain’t.

So what lies ahead? Are we all lemmings heading for the inevitable cliff? Or will human ingenuity find a way through, leading to the more ‘beautiful world’ that some envisage?

Here Be Monsters eschews false optimism. The digital age is here to stay, as far as anyone can tell. Billions of people are wedded to their devices, be they phones or pads or computers. The ages of television and radio seem almost benign in comparison, if we look through the lens of human connectivity. Nearly forty years ago, I recall my teenage son switching off the TV in my parents’ home, causing my father to blanch at this unforeseen intrusion. But my lad was simply trying to facilitate conversation without the visual and verbal distraction of the silver screen. Today, we are distracted to an extent unimaginable back then. People walk their dogs and their children, seemingly oblivious to their surrounds but intensely engaged with the phone in front of their face. We are privy to the conversation of countless others, in cafés, on public transport, and all manner of places where once there was a possibility of silence. Even – horror of horrors – in our local library! We email and text ad nauseam, exchange gossip and photographs and links to this and that – and to what end?

Well, you could say we are cheerfully, combatively, or cryptically communicating with one another. Yet the quality of this communication is another thing. King refers to ‘technologies of absence’. Much of what transpires these days by way of ‘communication’ is not done face-to-face but in some virtual format. The pandemic drove home the possibilities and the limitations. When push comes to shove, most of us – and here I make an assumption – would prefer face-to-face. In other words, the presence of others rather than the absence. Participation in Zoom conversations and workshops brings this home. Something is lost – something intrinsic to the human-to-human connection.

Contemporary literature has begun to address these implications. Roisin Kiberd’s book, The Disconnect, traces her personal journey through a series of essays. Born on the cusp of the World Wide Web, she shines a spotlight on how enticing that world can become:

‘I too am addicted to the screen. Sometimes I think I have spent so much of my life online that I was raised by the Internet. I’ve forgotten where the borders are, where technology ends, and where I begin. Am I a mutant? The cyborg? Or just an ordinary human?’ She goes on to say that ‘our technology is changing us, in ways we have yet to understand’ and ‘it was once claimed that the Internet would liberate us. Techno-utopians claimed online life would allow us to transcend gender, age, class and race, and to construct our own identities. It hasn’t turned out this way. Instead we’ve been led into fixed identities, each person given a biography, a Timeline, and a filter bubble of their own. Perhaps I am a techno-dystopian. Over the years, I’ve experienced a slow depersonalisation; cut off from reality, from sincerity and sensation, I felt urged to compete in a scrolling world. I’ve been conflicted, at times wanting to be the ideal data subject, then distrusting technology, even as I turned its surveillance on myself.’

Based in Dublin, Kiberd contrasts the redeveloped port area into a techno-hub with nearby areas replete with homelessness and dislocation. But the gleaming buildings and the service outlets that support a myriad of young workers are themselves a sterile trap. The author exists uneasily and often unhappily in this brave new world.

Sally Rooney, an Irish contemporary of Kibert, deals with these dilemmas in her third novel, Beautiful World Where Are You? Best friends, Alice and Eileen, type deep and meaningful emails to one another. They are articulate and at times funny. When alone, Eileen compulsively checks her feeds – her expression never alters, whether she hits upon something personal or a global catastrophe. The characters Rooney creates reflect the impersonal zeitgeist of the Internet age.

King articulates the insidious and often unforeseen byproducts of technology run rampant. Artificial intelligence – which has been better described as ‘algorithmic imitation’– is often included as part of a suite of perceived threats, such as global warming, nuclear warfare, severe pandemics, societal breakdown, and populist politics.

In 2021, Australian Labor politician, Andrew Leigh published What’s The Worst That Could Happen? where he looks at existential risk and extreme politics under various headings of which AI is one. He mentions a 2017 poker tournament in which a new AI program, Libratus, trounced the world’s best poker players. As one of them, Jimmy Chou, noted: ‘the bot gets better and better every day. It’s like a tougher version of us. The first couple of days, we had high hopes. But every time we find a weakness, it learns from us and the weakness disappears the next day.’ Chou’s remarks seem like a metaphor for what so-called AI has become and is becoming. From a technical perspective, cleverer, smarter, and much more powerful than humans (ordinary and extraordinary) in solving certain challenges. Note I said: ‘from a technical perspective’. The limits of AI – if there are any – are inherent to any discussion about it.

The rapidity of change is mind-boggling. As Leigh observes, genetic evolution takes thousands of years to bring about noticeable changes in humans. By contrast, advances in computer coding provide instant adaptability, allowing technological change to occur in the blink of an eye. This was brought home to me when I watched a discussion between the Emir of the UAE and Jensen Huang, the CEO of Nvidia. In a state approaching unqualified glee, Huang described the exponential acceleration in processing power – trillions of CPUs, taking ‘artificial intelligence’ into realms that are still unimaginable.

Nothing in that discussion indicated a potential downside. Quite the reverse. When asked a question from the audience about education, Huang commented that the study of biology is important, if we are to understand the seemingly inevitable move from what we know as the life sciences into the field of engineering that underpins the development of AI. Competent engineering is offered as the solution to our human future. Tellingly, no mention was made of ethics or protocols. And I doubt whether the dehumanising implications of this kind of thinking are the subject of earnest discussion in the playrooms of Silicon Valley.

King is under no such illusions. ‘For all their obvious magical thinking, the New Immortals are in thrall to the idea of the future as set out in trans-humanism: a future in which humanity merges physically with smart technologies, whether in the form of nan bots that deliver drugs with incredible accuracy, biochemical preparations that enhance our cognitive capacities, or the brain – computer interfaces dreamt of by Elon Musk and his equivalents. They dream of a cyborg future, in other words, in which organic and non-organic systems meld into a single being, no less human for having been so melded.’

To question this propulsion towards a so-called enhanced human – one that has been ‘engineered’ – does not mean throwing out the technological baby with the bathwater. Humans have always made things and will continue to do so. And as Stephen Pinker, in his various works, continues to remind us, life on Earth has become not only longer but much more tolerable (for most) since we emerged from the caves. Our evolutionary journey has been one that can be captured by the word ‘progress’. But therein lies a cautionary tale. We are fast reaching a point where the price may be too high. Iain McGilchrist has dealt with this extensively in his opus, The Matter With Things, in which he describes the individual and collective impact of a dominant left-brain culture that involves control and exploitation rather than one that is mediated by the holistic overview of the right brain. I was reminded of McGilchrist’s work when I read Here Be Monsters, as I suspect both authors have much in common although they come from different angles.

King is not shy in challenging the prevailing economic paradigm, drawing from Swedish activist Greta Thunberg who describes ‘the notion of endless growth on a finite planet as a fairytale.’ While applauding Thunberg’s emphasis upon ‘this insane logic’, King offers the caveat that it is ‘often insufficiently cognisant of the way that attempts to shrink the economy would increase the already vast inequalities that exist between the global North and South. People in developing countries may need to increase their ecological footprint in order to achieve food security and social justice, often by increasing agricultural production.’ Moreover, ‘moral arguments that people in the North should reduce their consumption are unlikely to succeed without a very different political culture. Even most of the environmentally-conscious still engage in consumption habits that would be unsustainable if extrapolated to the planet as a whole, never mind a global population that could touch an 11 billion by the century’s end. That is perhaps the biggest problem we face in terms of climate action.’

Hear, hear!

King makes it clear he is not anti-progress. Merely that we should think about what ‘progress’ might entail from the more rounded human perspective. Neither does he pretend he has the answers as to how life might become just and sustainable. Echoing Jem Bendell in Breaking Together, King says ‘the answer would have to entail some inversion of the local, the national and the global – that we would have to produce as much as we could as close to our communities as possible, while the State played a greater role coordinating and administrating basic infrastructure. We would also need agreements at the supranational level to manage global resources and ensure that poor countries could develop sustainably. These arrangements would need to be founded on a deep commitment to democratic consultation….’ And: ‘Such a system could only come about, I imagine, through a combination of local initiatives and radical action at the political level. But beyond this… Well, I just don’t know.’

Neither do I. And neither do those folk with whom I converse. But there is recognition it serves no purpose to pile aboard, with or without the dubious guidance of social media opinionistas, and blame ineffective politicians, media titans, and tech billionaires. We have choice, those of us who live in democracies which – for all their faults and frustrations – allow citizens the privilege of the ballot box rather than coercion into group-speak by totalitarian regimes. Unless we are blinded by self-interest and short-term thinking, we can educate and motivate ourselves to think globally and act locally. (And, as a nod to online outlets like Fremantle Shipping News, ideas and opinions can be shared regularly and respectfully.) Thus, from a space of empathy and compassion we can participate in the public square discourse, and potentially influence political parties and their leaders. To do otherwise, as King and others infer, is to abrogate personal responsibility. To do otherwise, I suggest, is to retreat into cynicism or apathy. And to do otherwise is to abandon any vestige of hope that a more beautiful world is possible.

My home library seems to be awash with thoughtful treatises dealing with the complexities and challenges of modern life. Rather than regard the authors as mere harbingers of bad news, I’ve been both inspired and chastened by books that oblige me to think more deeply and feel more intensely. As I write, my eyes are drawn to the cover of Juice, hot off the press from the pen of Tim Winton – another writer with a strong Fremantle connection. As a conservation campaigner, Winton has a stack of runs on the board. Like Richard King, he has channelled his anguish into creative outlets that compel readers to engage and reflect. Perhaps the ghost of James Baldwin is smiling somewhere. Yes indeed, nothing of consequence can be changed – until it is faced.

By Bruce Menzies. Based in Fremantle, most of the time, Bruce Menzies is the author of three novels, a family history, and a recent memoir. Details at BruceJamesMenzies.com If you’d like to read more of Bruce Menzies’ work on Fremantle Shipping News or listen to a fascinating podcast interview with Bruce, look here

For our podcast with Richard King, author of Here Be Monsters look here

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

* If you’d like to COMMENT on this or any of our stories, don’t hesitate to email our Editor.

** WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

*** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!