Western Australia, and in particular the Perth Metropolitan Region, once had what was, arguably, the best planning system in the world, up until the late 1970s.

Over time numerous changes have been made to the system, in more recent years under the guise of “planning reform”.

Sadly, in my opinion, virtually every change made after that time, by successive governments of both persuasions, has involved a retrograde step. Each has made the system worse, not better.

So that begs the questions –

WHAT WAS SO GOOD ABOUT THE EARLIER SYSTEM? AND WHAT HAS CHANGED?

From 1963, for a time, we had a planning system with these elements –

* An historic statutory authority, the Town Planning Board. From 1928 the TPB, coupled with the best land tenure system in the world, directly controlled all land subdivision, provided a fundamental regulatory system, ensuring consistency across the State and oversaw the preparation of local authority town planning schemes.

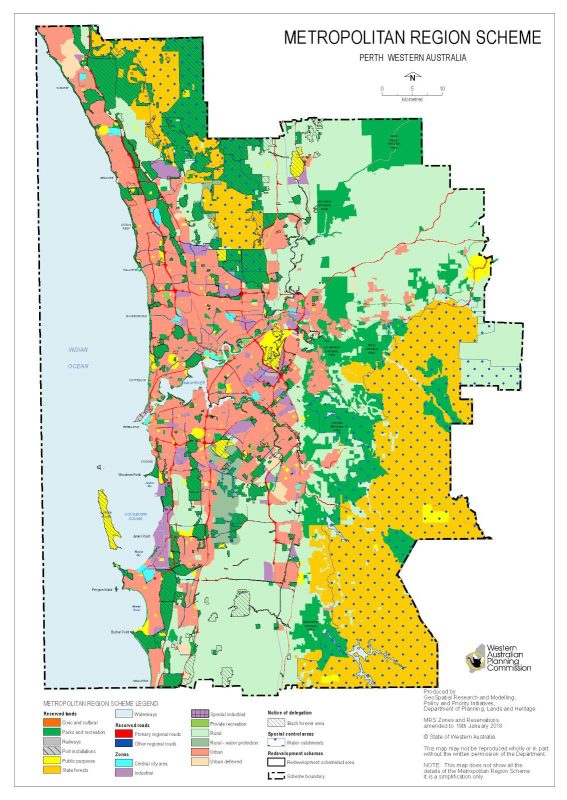

* The 1963 Metropolitan Region Scheme. The MRS was probably the first and best metropolitan town planning scheme in the world. It was based on the world-leading 1955 Plan for the Metropolitan Region of Perth and Fremantle (the famous Stephenson-Hepburn Plan). It was a plan adopted by the Parliament. Major amendments to the MRS required the consent of both Houses of the Parliament.

* To manage the operation of the MRS a new authority, the Metropolitan Region Planning Authority (MRPA) was created, under an independent chairman. The Authority comprised the major infrastructure-provision agencies together with an elected local government councillor from each of four sub-regions of the Region. It had independent funding, the Metropolitan Region Improvement Fund, financed from a special tax on properties in the Metropolitan Region. The MRPA exercised the powers and responsibilities of administering the MRS. These included purchase of reserved lands, notably for open space, education sites and major transport networks; for developing Metropolitan Improvement Plans; and for control of development on regional reservations.

* A well-staffed and equipped professional Town Planning Department (the TPD) had a publicly respected professional Permanent Public Service Head and a separate professional Chief Planner. These positions respected and gave equal weight to strategic and statutory planning. The TPD provided professional advice to the TPB, the MRPA and the Minister for Planning, and professional guidance to local authorities.

* Local authorities vested with the power and responsibility to create town planning schemes and, subject to State and MRPA exceptions, to control development on land within their boundaries.

So, WHAT HAS CHANGED? AND WHAT HAVE BEEN THE CONSEQUENCES?

Credit Unsplash in collaboration with Allison Saeng

Well –

* The TPB and the MRPA were abolished and subsumed into a single statutory body (currently the WA Planning Commission). While this potentially offered the prospect of greater integration of related functions, it led inevitability to a loss of focus on distinctly different functions.

* Abolition of the MRPA removed a remarkably successful mechanism for collaboration between infrastructure agencies and with local government, a major setback to the planning of the Metropolitan Region.

* The position and role of Chief Planner were abolished, resulting in a loss of dedicated vision, continuity, and direction, especially critical for Metropolitan Perth.

* From the early 1980s on, the public service became progressively more politicised. Planning departmental heads, along with the others, are appointed on limited contracts, and often lack professional planning expertise. Again, this has resulted in loss of continuity and vision, an absence of independent and fearless advice, and a growing disinclination to offer unpalatable advice to government. Planning decisions have, arguably, become more politicised.

* Along the way there have been attempts at amalgamating planning with other government departments, in the illusory belief that this would offer administrative efficiencies and even encourage collegiate decision-making. All such changes have been well-intended. All have been misguided. All have been failures. The current DPLH is only the latest of many. All departments, especially professional ones, need to have a clear, singular focus and a strong individual voice. Cabinet and interdepartmental committees and the like are the places for resolving conflicts between them. The MRPA was the most successful and proven such mechanism ever, in my experience, and the government of the day had to junk it. Perhaps it was so successful that it became a threat to the political establishment.

* Planning powers and responsibilities should always be vested in public authorities. It is remarkable, and should ring alarm bells, that a property developer, the State Development Agency (SDA), has unconstrained power to override the MRS, a power previously only possessed by the Parliament. The SDA’s powers derived originally from a special case, the East Perth Redevelopment Authority, the first agency given power to override both the local planning scheme and the MRS. The power was much too attractive for the successive development authorities to consider yielding it up.

* The SDA, as the State’s premier land development agency, has a history of predecessors, beginning, in the 1970s, with the Urban Lands Council. The ULC was charged with ensuring an adequate supply of affordable residential land. It was a vitally important need then, and has never been so important as it is now. In due course the ULC expanded and morphed into successive agencies, initially to also ensure an adequate supply of industrial land, and finally, and perfectly predictably, into a profit-making development arm of government dedicated, like its private sector cousins, to turning a buck. That evolution was predictable from day one, as soon as turnover and surplus (ie profit) became measures of success. Oh, the lure of gold, even to the State.

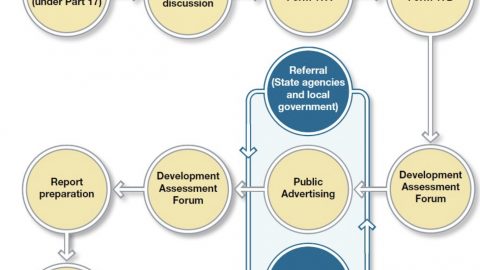

* The creation of Development Assessment Panels (DAPs), ostensibly, and to a degree defensibly, was predicated on problematic decision-making by local governments and a lack of trust in their capability to deal with large projects. It was also a response by State government to requests by the major developers to get around the democratic basis of local government decisions and substitute decision-making by appointed “experts”, untroubled by sensitivities to the local environment.

* Then State Development Assessment Authorities (SDAUs) were added to the system, on the questionable premise that COVID had created an urgent need for quick planning approvals for large developments in order to keep the economy alive. Given the lateness of the initiative, the obvious facts that no large developments could have put workers on sites in less than three years and that the industry was already desperately overheated and construction workers extremely difficult to find, somewhat diminished the credibility of the rationale. Renewing the SDAUs long after COVID ceased to be a concern simply confirmed the State government’s likely true purpose: to further weaken the power of local government.

* The system is again undermined by extending to private landowners and developers powers to initiate major developments and even planning instruments, such as Precinct Structure Plans, at the expense of local governments and local communities.

* Ironically (or perhaps not so ironically), these changes to undermine local government planning powers have coincided with an exponential growth in numbers of local government planners and, at least theoretically, in their planning capabilities.

* The dangers of undermining the planning role of local government are obvious. Putting control of important decisions that affect local communities in the hands of outside “experts” leads inevitably to a reduced understanding of the context and hence of the quality of decisions. At the same time local authority planners are discouraged from nuanced analysis and recognition of local conditions and led into generic thinking.

* There is now a common public perception, seemingly not universally shared by the planning profession itself, that the planning system in Western Australia is failing, and that the failure is systemic.

* This failure, it must be said, has worsened despite, in fact because of, conscious attempts by governments of both persuasions, at different times, to reform the system, or elements of it. None, apparently, has seriously considered what might have been lost by making the changes that have been made since about 1970, when we had a system that worked extremely well, was in fact world-leading.

* Almost all public criticism of the planning system now comes from local communities and individual residents, much of it expressing overt frustration and even anger. It is usually triggered either by proposed developments, especially those that are determined by/approved by the DAPs or SDAU, or by planning scheme proposals, often initiated by the WAPC or the Minister for Planning. These decisions, especially by the DAPs and SDAU, are, with some reason, seen as favouring developers against local communities.

* Local governments have, understandably, also become more vocal in criticism of the system, because of the attacks on their autonomy and consequent development approvals given contrary to their advice, although their commentary appears more constrained than that of their citizens.

* In all of this the planning profession itself has been remarkably silent, compliant, it seems, in the face of a failing system. Why is this? It is partly because so many planners are in public employment – either local or State government – and so are formally constrained by their employment from critical public comment? Likewise, consultants and practices in the private sector are scared of upsetting either their client base (private or government) or the local or State government agencies whose goodwill they depend on for approvals and cooperation.

The history, such as it is, begs the the final question –

WHAT CHANGES MIGHT, OR SHOULD, BE MADE TO IMPROVE THE SYSTEM WITH A VIEW TO ACHIEVING BETTER SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL OUTCOMES?

Credit Grégoire Thibaud

Let me suggest just a few, not necessarily in priority order, to start a conversation –

* Reinstate an equivalent of the largely autonomous MRPA, an agency independent of the WA Planning Commission, not subject to ministerial direction, and with its own staff and guaranteed funding base, the Metropolitan Region Improvement Tax.

* Extend the boundaries of the Metropolitan Region, with the tax base, to include the Peel Region rather than pretend that they are separate regions.

* Recognising the necessity of a regional approach to planning, especially of urban regions, make legislative provision for the creation of other regional planning authorities, with similar autonomy.

* Keep the WA Planning Commission as the statewide umbrella planning agency, with oversight of State-level planning policy and planning schemes, etc, except as constrained/limited by specific powers defined for the Metropolitan Region and other regional planning authorities; and as a valued source of professional guidance to local and regional planning authorities.

* Strengthen, not weaken, local government planning powers generally, including extending control over land subdivision within prescribed limits.

* Review the structure plan system, including the proper basis for initiation, their scope, the process for preparation and public review, statutory standing etc.

* Carry out a review, with public consultation/participation, into the criteria for WAPC or Ministerial call-in of development applications, including reference to other decision-making agencies such as the DAPs.

* Carry out a public enquiry into the experience and functioning of DAPs and other decision-making agencies with a view to determining their worth and providing clear and defensible limits to their employment. Abolish the SDAU, except as a possible source of advice to the WAPC or Minister on developments meeting the criteria for WAPC or State call-in of applications.

* Carry out a public enquiry into the impact of planning processes and policies, including especially the imposition of developer “contributions” and infrastructure headworks charges, on the cost of residential land and hence on housing affordability.

* Establish a transparent and consultative public process to make it more difficult for the State government to set aside the stated purposes of State land reserves and State heritage-listed places.

* Remove the major, or preferably all, planning powers of state development agencies and reinstate the primacy of the MRS and other regional schemes.

* Strengthen the professional capabilities of local government.

* Recast the residential arm of the SDA or, preferably, create a new state agency, with land acquisition and assembly powers, designed to operate in the residential land and housing market and charged with ensuring an adequate supply of affordable land, including redevelopment sites in established residential areas.

* Charge that agency with the task of solving the problem of achieving appropriate – that is, well-designed, extensive and affordable – redevelopment of ageing low-density residential areas.

By Ken Adam, APTC (Arch), Dip TCP (B’Ham), LFRAIA, LFPIA, FAIUS. Ken Adam graduated in architecture from Perth Technical College in 1964 and in planning from the University of Aston in Birmingham, UK, in 1968. After some years in the Public Works and Town Planning Departments of WA, he established his own practice as an architect and planning consultant in 1974. He more or less retired from full time practice in 2012. He is probably best known as the author of the Residential Design Codes (the R-Codes) and as Chairman and spokesman for the urban think-tank CityVision.

Ken Adam is a Life Fellow of both the Planning Institute of Australia and the Australian Institute of Architects and is an Hon Fellow of the Australian Institute of Urban Studies. He is a recipient of the Architect’s Board Award.

* This article first appeared in Issue 4, 2024, of Thought Pieces as one of a series of short articles by individual members of the Planning Institute of Australia’s Western Australian division

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

** If you’d like to COMMENT on this or any of our stories, don’t hesitate to email our Editor.

*** WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

**** And don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!

***** AND Shipees, here’s how to ORDER YOUR FSN MERCH. Fabulous Tees with great options now available!