It’s twelve days since I’ve seen any sign of another human. No roads, fences, litter, nothing – just pristine wilderness.

It was the mid-1970s and I was the sole Fisheries & Wildlife officer responsible for the top half of Western Australia. One of the local Aboriginal elders told me there was talk of wildlife smuggling in a remote region of the Kimberley, so I had headed out to investigate. Apparently, people were landing aircraft on disused WWII airstrips to collect animals, and some of his people had been offered bribes to catch and deliver birds, snakes, and lizards.

Live animal smuggling is a highly lucrative but very cruel industry, with many of the smuggled animals perishing. The World Wildlife Fund estimates the annual value of smuggling at 12 billion dollars US – after habitat loss, it’s the largest threat to the future of many species. Even back in the 70s, a pair of Major Mitchell parrots could fetch $100,000 on the Asian black market.

I’d left the last dirt road and headed overland in my government-issued Land Rover.

A typical 1975 Land Rover

The mighty Fitzroy River only flows in the summer monsoon. The rest of the year, it forms a series of lakes and ponds and dry riverbed. I was following its banks where I could, but often had to deviate long distances where the river had cut through rock and rough terrain.

I came to an expansive alluvial plain caused by the river’s flooding over millennia. A wall of dry kangaroo grass completely surrounded my vehicle. I could see nothing but brown grass ahead and to the sides. The grass was too thick to open the door, so I climbed out of the driver’s window and onto the hood. Standing up, I could see over the top of the grass to a distant hill about three kilometers away and took a compass reading.

Fitzroy Rover plain. Credit ABC

The grass prevented the flow of cooling air, and as a result the engine’s temperature gauge had been steadily climbing. I had to stop, climb out, and clear the radiator of grass stalks and seeds every hundred metres or so. Back in the driver’s seat, I steered by compass. Slowly, slowly – the ground was flat and even, but I had no way of telling if I were about to drive into a boulder, a pothole, or drop into a canyon.

There was not a cloud in the sky and the tropic sun and lack of air elevated the temperature inside the Land Rover to 44 degrees. With the humidity at 75%, it was seriously uncomfortable.

After a couple of hours of this torturous process, I came to the end of the tall grass. Laid out before me were several hundred acres where the grass had been burnt to the ground, no doubt caused by monsoon season lightning – probably a month or two earlier, since there was a carpet of green shoots covering most of the blackened areas.

Up ahead I saw a donkey foal, standing by itself in the middle of nowhere, with no sign of its mother or a herd. This was a feral donkey, about two or three days old.

Not the donkey foal, but a donkey foal

First imported into Australia as pack and wagon-pulling animals in the late 1800s, domestic animals escaped from captivity and bred into wild herds that freely roam the great expanses of northern Australia. They’re now widespread in semi-arid parts of WA. Excellent conservers of body water, they can tolerate extreme dehydration, making them particularly successful in dry conditions. Unfortunately, like other feral animals in Australia, they do considerable damage to the environment and compete with native animals and livestock. They’re considered a pest to be controlled.

Pest or not, I couldn’t leave this little guy to suffer. As I drove up, he started to walk away, so I followed – slowly, in order not to frighten him. After a hundred metres or so, he came to a halt. As I got out of my truck he turned around and walked right up to me. This little guy needed milk badly. I had none fresh, but I carried a can of powdered milk in my camping provisions. I filled a plastic bag with water and powder, mixed it by shaking, pierced a small hole in one corner and offered it to my new friend, “Charpie.” He drank it all and a refill; then nuzzled up to my hip. It seemed that I had shown him all the necessary qualities of a mother – and now he had adopted me. I lifted him into the passenger seat and continued on my way. He sat on the seat, with his front legs elevating his head to see out of the window. My companion seemed relaxed and content with his new circumstances.

That evening I made camp beside a small waterfall with a lagoon below it. Camp consisted of a fold-up camp cot (to keep me above any snakes and wandering scorpions) and a mosquito net hanging from a tree branch above. A small fire to cook with completed the picture. I tethered Charpie to the tree beside the cot, fed him again, and turned in for the night.

Around 2:00 am whilst I was in deep sleep, Charpie came up to the cot and, with his mouth right beside my ear, let out a brain-piercing “Hee Haw!!” It scared the proverbial out of me. I leapt up, having no idea what the hell had happened, got tangled in the mosquito net, and fell over onto the ground. Charpie, unfazed, stood in the moonlight gazing at me intently.

A dog bark, and then another, came from the river. I grabbed my flashlight. What dogs would be out here in the bush? Australia’s wild dog, the dingo, doesn’t bark and there shouldn’t be any domestic animals within a hundred kilometres.

I swept the riverbanks with light. 30 metres away, two pair of red eyes were looking in my direction. Crocodiles have red eyes and bark like dogs. These two were advancing toward me. The closest one was a huge beast, around four or five metres long, I guessed.

A freshie

Western Australia has two species of crocodiles – the relatively harmless, smaller freshwater or Johnson River Crocodiles and the very, very, dangerous saltwater monsters (salties) that grow up to six metres long. I knew a fair bit about crocs. My father had hunted crocs after the Second World War, so I had heard his stories and seen his souvenirs and photos but had no idea that salties would be this far inland.

There were few opportunities for returning soldiers after the war. My father and a half-dozen mates went to the Kimberley to eke out a living in the extremely tough and dangerous business of catching and skinning crocs. The skins were highly prized by the international fashion industry. Over the next 20 years, the skin trade and sport-shooting took the crocodile population close to extinction and in 1970, WA became the first state to legally protect the animals. Since then, their numbers have burgeoned.

I did not waste a second. I grabbed Charpie and got both of us into the Land Rover. About a kilometre from the river, we stopped to sleep again. Charpie in the back, and me, uncomfortably, in the front seat. I figure that finding my donkey was indeed good fortune. He’d alerted me to the crocodiles and helped me live to tell the tale of his heroic service.

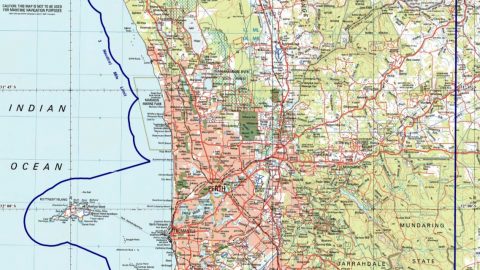

Charpie rode around with me for a couple of weeks until I needed to drive the 2,200 kilometres from my outback posting to Perth. I had been transferred, so I packed all my gear into my own 4×4 short-wheel based Land Cruiser, put Charpie in the back of the cab on top of all my stuff, and headed off. We stopped every two hours so Charpie could stretch his legs, pee, and drink some water.

Your typical 1975 short wheel base Toyota Landcruiser

The “highway” was a two-lane dirt road through desolation. The only signs of civilization were refueling roadhouses about every 300 kilometres. At about the 1,000 kilometre mark, I pulled up at such a roadhouse to buy petrol. It had only been an hour since Charpie had been out of the vehicle, so I left him in his bed in the back and went into the old corrugated-iron building to buy a coffee.

In my absence, Charpie managed to climb from the back onto the front seats. In standing position, he peed at least a litre all over the seats, splashing the dash, doors, and floors, and then climbed back into his bed.

Water was a scarce commodity at the roadhouse, so my only recourse was to wipe the vehicle interior down as best I could with a wet cloth. I threw a towel over my seat and drove the rest of my journey with the windows down to relieve the stench of male donkey urine.

Charpie lived in my backyard until almost fully grown, and the neighbors complained about me keeping livestock in town. A dairy farmer friend took him in where he lived to a very ripe old age.

* By Jay Harman

You’ll find more great Fremantle Shipping News articles by Jay Harman right here.

While you’re here –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!