Last night, at a packed out forum at Foley Hall, University of Notre Dame Australia, Fremantle, hosted by University of Notre Dame Australia and Fremantle Shipping News, panellists and audience members met to discuss The Voice to Parliament and The Executive Referendum proposal.

Credit Grant Taylor

The forum, moderated by Geoff Hutchison, saw a panel comprising Professor Cheryl Kickett-Tucker of Curtin University, Professor Steve Kinnane of Notre Dame University, Fremantle Shipping News Editor Michael Barker and Professor Martin Drum of Notre Dame University address the significance of The Voice and what might be considered the political and legal implications of establishing The Voice.

Credit Grant Taylor

A large number of attendees at the forum indicated, by a show of hands, they had not had the opportunity to read the Final Report of Professor Tom Calma and Professor Marcia Langton on the design of The Voice – The Indigenous Voice Co-design Process: Final Report to the Australian Government (Canberra: National Indigenous Australians Agency) July 2021 – which for ease of reference we will call the Calma and Langton Report – but would like to, especially if it could be presented in an shorter, condensed form.

So, in response to that request, in this first Getting The Voice feature, we reproduce a review by Professor Tim Rowse first published by Australian Parliament House in March 2022, reviewing the Langton/Calma Report and including a concise account of the key features of the authors’ proposals. Professor Rowse’s observations and analysis, as readers will soon discover, remain as pertinent today, as the campaigning for the YES and NO cases ramp up, as they were a year ago when his review was first published.

Professor Rowse is a former Professorial Fellow in the School of Humanities and Communication Arts and is Emeritus Professor in the Institute for Culture and Society at Western Sydney University. He has taught at Macquarie University, the Australian National University and Harvard University (where he held the Australian Studies chair in 2003-4), and he has held research appointments at the University of Sydney, the University of Melbourne, the University of Queensland and the ANU. Since the early 1980s, his research has focused on the relationships between Indigenous and other Australians, in Central Australia (where he lived from 1989 to 1996) and in the national political sphere.

HERE IS PROFESSOR TIM ROWSE’S REVIEW OF THE LANGTON/CALMA REPORT

Conservatives who are unsure what position to take on Indigenous constitutional recognition seem to be the intended audience of the Final Report of the Indigenous Voice Co-design Process, released in December 2021. The Final Report signals its politics at one point by choosing certain words when rejecting two suggestions. One suggestion was from a group of legal scholars that includes Professor Megan Davis: that the National Voice have the ‘powers and privileges of a parliamentary committee to compel people to appear as witnesses or produce documents’ (p.172). The other was from ANTaR, suggesting a (Senate) ‘”estimates” process as another direct accountability mechanism’ (p.172). The Report labels these two suggestions ‘inquisitorial’, and it envisages instead a ‘flexible, good-faith partnership between the National Voice with both Parliament and Government’ (p.161).

The political strategy of the entire report can be read into the contrasting connotations of ‘inquisitor’ and ‘partner’. The strategy may be sound. The prospect of an election and then (possibly) a referendum in 2022 makes it desirable, now, to craft an unthreatening model of the Voice.

What have conservatives to be afraid of? Liberal Senator Andrew Bragg keeps prodding his Coalition colleagues with this question, urging the Morrison government to commit to a referendum on the Indigenous Voice and to endorse a Yes campaign that would entrench the Voice in Australia’s constitution. His campaign may succeed, as the Liberals may judge that one way to woo disenchanted Liberal voters is to present the Coalition as champion of the Indigenous cause. Were the Coalition and Labor to come together, after the next election, to endorse the Yes case in a referendum, it would probably be carried.

By giving a substantial answer to the question: What will the Indigenous Voice look like? Tom Calma’s and Marcia Langton’s Final Report makes that result more likely. Over the next few months, many voters will want to know what the Voice is. They will soon be asked to choose between a Coalition that wants to legislate the Voice and a Labor party that has promised a referendum on the Voice, followed by legislation. A referendum could be held as early as September 2022, so voters will want to know what they were being asked to put into the constitution.

To meet the needs of this moment, a model of the Voice must satisfy two political requirements: persuade Indigenous opinion that it would be a substantial reform (and a meaningful form of constitutional recognition), and reassure conservatives that the Voice will not unduly empower Indigenous Australians.

The Final Report addresses Indigenous opinion by emphasising that the Voice will not be elite-driven but have strong grass roots. Existing Indigenous organisations are to be the basis of the 35 Local & Regional Voices making up the Voice’s bottom tier, and the National Voice will come later, as a derivative body. The Final Report addresses conservative caution in several ways: explicitly denying the National Voice an ‘inquisitorial’ role; refusing to propose a model of funding that would insulate the Voice from the annual budget; plotting a slow implementation plan that requires much intergovernmental cooperation; and subjecting the 35 Local & Regional Voices to a process of government evaluation before recognition.

From the bottom up

The Final Report’s model is heavily weighted to the Local/Regional level. First, the boundaries of the 35 Voices must be determined, through discussions between governments and Indigenous organisations. Then, in each region, either a ‘Voice’ would be designed from scratch or (more likely) existing Indigenous organisations would be adapted. Rather than present a blueprint of Local & Regional Voices, the Final Report offers nine guiding design principles for the 35 regions to apply. The 35 Voices will acquire legitimacy, in Indigenous eyes, by virtue of their links to other existing bodies and by not duplicating or undermining organisations that are seen to be working. Each will ‘build on and leverage existing approaches wherever possible, with adaptation and evolution as needed…’ (p.50).

Regions breakdown by state/territory (From the Final Report)

What will the 35 Local and Regional Voices do? Each will share data with and advise all three levels of government and relevant non-government bodies about the delivery of services and about investment in the region. As well, the Local & Regional Voices within each State and Territory will get together to select the National Voice members from their State or Territory.

The Voices (Local & Regional and National) will get their responsibilities from the Commonwealth’s enabling legislation. Following this foundational step, the Commonwealth will engage with the State and Territory governments, resulting in agreements with the Commonwealth that may include matching State and Territory legislation. Through this framework all three levels of governments will recognise and work with the 35 Voices. Governments’ interactions with the 35 Local & Regional Voices are imagined as effecting what the Report calls a ‘systematic transformation of government ways of “doing business”’ (p.17).

Let us imagine what that could mean. The advice coming from Local & Regional Voices may well include that governments should spend more money and spend it in ways different from before. Were all eight governments to yield readily and repeatedly to such advice it could be a change worthy of the phrase ‘systematic transformation.’ But will the legislated framework oblige the three levels of government to act on advice from the 35 Voices? The Final Report expresses the anodyne hope that each State and Territory government will coordinate across its portfolios and agencies more than it does now, but it says nothing more about ‘systematic transformation.’

What would motivate the eight governments’ to authorise (perhaps by legislation) a framework that obliged them to act on Indigenous Australians’ advice? For Local & Regional Voices to make a difference to what governments do much will depend on the Commonwealth’s carrots and sticks. It is possible to imagine the Commonwealth creating incentives (tied grants?) for State and Territory and local governments to act in certain ways towards the 35 Local & Regional Voices. However, whether such obligations would be legislated remains to be seen. Because the terms of reference of the National Co-design Group forbade drafting the establishing legislation, the Final Report is silent on whether and how State and Territory and local governments could be motivated to act on the advice given by the 35 Voices.

In the Final Report’s only reference to the substance of the legislation enabling the 35 Voices to function, the topic is not what such legislation will require of governments but what it will require of the Voices.

Each Local & Regional Voice will need to meet a set of minimum expectations based on principles and be formally recognised. The recognition process and assessment criteria will be set out in legislation (p.23)

The other matter that must be determined by legislation, according to the Final Report, is ‘the provision of funding certainty and appropriate safeguards’ (p.14), but the Final Report makes no suggestions about how ‘funding certainty’ could be legislated nor about any ‘safeguards’.

Legitimacy

In attaching importance to building the Local & Regional tier of the Indigenous Voice the Final Report recognises that under the federal structure of the Australian state, many of the policies, laws and programs that affect Indigenous Australians are the responsibilities of State, Territory and local governments.

Local & Regional Voices would have a different and more expansive role to that of the National Voice. They would partner with all levels of governments, providing priorities and guidance and shaping decisions close to the level of impact for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Local & Regional Voices would have their own role and are not subordinate to the National Voice or vice versa (p.119).

However, the Final Report gives an additional reason for the formation of the 35 Local & Regional Voices. It argues that the legitimacy of the National Voice – in the eyes of Indigenous Australians – will rest on the effective operation of the 35 Local & Regional Voices.

The Final Report is much concerned with ‘legitimacy.’ Both the National Voice and the 35 Local and Regional Voices could lack legitimacy, the Final Report warns, unless certain steps are taken. Local & Regional Voices need to involve ‘traditional/cultural leaders’ (p.58). Community involvement in Voice design, including assent to boundaries drawn between Local & Regional Voices, will also contribute to legitimacy. As well as striving for Indigenous legitimacy, each Local & Regional Voice must legitimise itself in the eyes of governments. Australian governments will formally recognise Local & Regional Voices only if each satisfies criteria set out in the enabling Commonwealth (and possibly matching) State/Territory legislation, mentioned above.

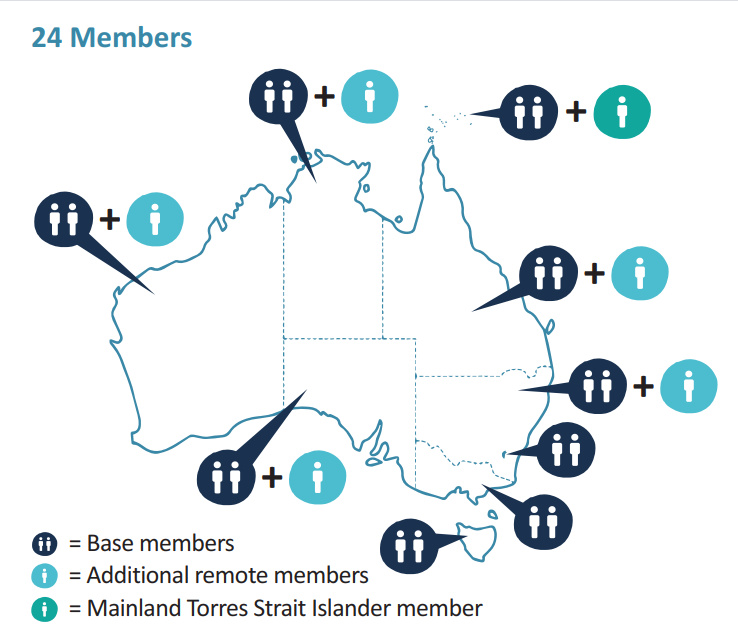

What will make the National Voice legitimate? The Final Report recommends that the National Voice have 24 members (3 representing Torres Strait, 3 each from Western Australia, South Australia, Northern Territory, Queensland, and New South Wales, and 2 each from ACT, Victoria and Tasmania). None will be government-appointed. Rather, the Local & Regional Voices within each State and Territory will meet to choose National Voice members from their respective jurisdictions. The Final Report calls this the ‘structurally linked’ (p.86) membership model, and it contrasts that way of choosing National Voice members with direct election. Direct election of National Voice members would not confer as much legitimacy on the National Voice, as it is likely that only a small proportion of Indigenous Australians eligible to vote would do so. The National Voice to the Parliament and government of Australia will be legitimate to the extent that its advice is based on ‘local and regional input’ (p.86).

The National Voice requires an additional legitimising measure, according to the Final Report. The 24 National Voice members must be submitted to the scrutiny of an Ethics Council which will ‘conduct a character test or fit and proper person assessment’ (p.141). Such a test will not be applied to persons chosen – by a variety of processes – to function in the 35 Local & Regional Voices.

In short, in several ways, the Final Report presents National Voice legitimacy as more problematic, and as derivative of ‘the strength, legitimacy and authority of Local & Regional Voices’ (p.12). Thus differentiated, the National Voice should come into operation only after the Local & Regional tier is operating. ‘Until the vast majority of Local & Regional Voices are fully established, the National Voice cannot be fully established under the structurally linked membership model’ (p.216).

How many of the 35 Local & Regional Voices would need to be up and running in order to constitute this ‘vast majority’? And who is to decide that number? The Final Report estimates ‘that it could take up to 3 years [after the enabling legislation] for the vast majority of Local & Regional Voices to be fully established’ (p.215). Only then will it be possible to establish the National Voice. Meanwhile, there would have to be an Interim Body for a National Voice, the Final Report suggests.

The moral authority of ‘advice’

As Paul Kelly pointed out in several articles in the Australian in 2018 and 2019, the conservative fear that the National Voice to Parliament would be a ‘third chamber’ is best understood as a reasoned apprehension of the moral authority of National Voice. To act contrary to advice issued publicly by the National Voice could be politically costly for any government. To reassure conservative opinion the Final Report has had to address this fear. It has proposed ‘consultation standards’ (pp.11, 159) that distinguish between what Parliament must do and what the public can reasonably expect it to do.

Parliament and Government would have an obligation to consult the National Voice on primary legislation that ‘overwhelmingly relates to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ (p.159) or that is a special measure for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within the definition of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth). Parliament and Government would be expected to consult on proposed laws and policies that have a significant or distinctive impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The Final Report then goes on to recommend that no court should ever be allowed to rule on whether a government was meeting these obligations and expectations. That is, the ‘consultation standards’ must be non-justiciable. While there would be political risk for a government or Parliament that did not adhere to the agreed standards of consulting the National Voice, critics could not litigate the matter. The Final Report’s insistence that interactions between National Voice and Parliament/Government be ‘non-justiciable’ is the designers’ most important emollient of the ‘third chamber’ fear.

Instead of ‘justiciability’, there should be ‘transparency’. The Final Report sees three ways for the interactions to be disclosed. Every bill’s explanatory memorandum would say whether and in what way the proposer of the bill had engaged with the Voice – a transparency obligation on the proposer of the bill, usually the government. The Voice would also table its advice in Parliament – a transparency obligation on the Voice, as the author of the advice. A third transparency measure would be to establish a new parliamentary joint standing committee; the Voice would have a strong incentive to participate in the work of this committee, and such a committee could become the main way in which the Voice talks to Parliament.

The authority of the Final Report’s model

It is possible that many advocates of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament will feel dissatisfied with Calma’s and Langton’s concessions – no doubt carefully deliberated – to conservative apprehensions. Could such critics come up with a stronger model of the Voice? Could they now say: Yes, we want a Voice, but not the Final Report’s model? There would be risk in departing from the model now before us. Its legitimacy derives partly from its leading authors’ prestige: Professors Marcia Langton and Tom Calma.

The model has also accumulated legitimacy from the slow, multi-voiced process of public deliberation over which Langton and Calma presided in Phase Two (February – July 2021) of the co-design process. The Final Report devotes several pages to describing this process. More than 9,400 people and organisations participated in consultations on proposals over a 4-month period. ‘This included 115 community consultation sessions in 67 locations with more than 2,600 participants, 13 webinars with more than 1,450 participants, more than 4,000 submissions and surveys lodged and more than 1,200 participants across more than 120 stakeholder meetings’ (p.188).

The Final Report’s statistics suggest the strength of Indigenous interest: 6 per cent of submissions from individuals were from people who identified as being Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (double their proportion of the Australian population); 90 per cent of individual submissions were from people who identified as non-Indigenous, with 4 per cent not answering this question. Of the 14 per cent of submissions identified as representing an organisation or group, 10 per cent were from Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander organisations or groups. Nineteen per cent of the individual respondents to the online survey were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders, and 31 per cent of the organisational responses to the survey were from Indigenous organisations or communities.

Critics of this model of the Voice may lament its concessions to conservative opinion, but they are unlikely to be able to come up with an alternative Voice without losing momentum towards constitutional recognition. If Australia is going to consider whether to put an Indigenous Voice in the constitution or even whether to legislate a voice, the model presented in the Final Report is likely to be the only one on the table. In producing this model, Calma, Langton and their co-design committees have taken a big step towards bipartisan agreement and thus to consummating the debate on constitutional recognition.

We should note that, while the Calma and Langton Report proposes 35 Voices around the country at local and regional levels, it is currently suggested that The Voice to Parliament and The Executive at the national level will comprise 24 members, as explained in this image –

We would also observe that the final choices made by the Albanese Government in the framing of the current referendum Question and Alteration text plainly reflect the recommendations made in the Calma and Langton Report, as a re-reading of The Question and The Alteration will disclose –

THE QUESTION

A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?

THE ALTERATION

Chapter IX Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 129 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice

In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

1 There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

2 The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

3 The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.

* By Michael Barker, Editor, Fremantle Shipping News

** Fremantle Shipping News supports the YES campaign

WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!