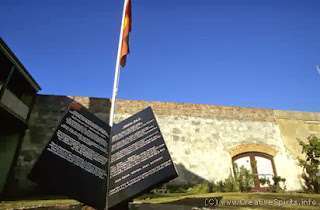

In a pleasant garden beside a colonial-era building, just north of the gates of Fremantle Prison, is a memorial to John Pat. He died at Roebourne Prison on 28 September 1983. He was 16 years old. The memorial is in the form of an open book in cast metal.

The words on the open pages are drawn from a poem entitled ‘John Pat’ by the late Indigenous playwright and poet, Jack Davis.

John Pat

Write of life

the pious said

forget the past

the past is dead.

But all I see

in front of me

is a concrete floor

a cell door

and John Pat

Agh! tear out the page

forget his age

thin skull they cried

that’s why he died!

But I can’t forget

the silhouette

of a concrete floor

a cell door and John Pat

The end product

of Guddia law

is a viaduct

for fang and claw,

and a place to dwell

like Roebourne’s hell

of a concrete floor

a cell door

and John Pat

He’s there- where?

there in their minds now

deep within,

there to prance

a sidelong glance

a silly grin

to remind them all

of a Guddia wall

a cell door

and John Pat.

(‘Guddia’ is a Kimberley term for a whitefella.)

John Pat’s tragic death while in custody led to the calling of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. That Commission handed down its report on 15 April 1991, some 30 years ago. The anniversary of that report has led to considerable discussion in recent weeks about whether, in the intervening years, there has been an improvement in the incidence and circumstances of Aboriginal deaths in custody, not just in Western Australia, but in all States and Territories. The sad conclusion would appear to be that there hasn’t been. Why is that so?

One fact that is often lost in the public debate on this issue is that the real problem is not that Indigenous people are more likely than non-Indigenous people to die while in custody, rather that they are more likely to be in custody than non-indigenous people. Being in custody is not just ‘doing time’ as the result of being sentenced to a term of imprisonment. It may be that you have been arrested and are being held in a police lock-up before being put before a court. It may be that you’ve defaulted in paying a fine. Or it may be that you’ve been refused bail and are awaiting trial or sentence.

The fact that gives rise to concern about deaths in custody is that Indigenous people are more likely to be in custody than non-Indigenous people. That is particularly so in Western Australia and the Northern Territory. There are many reasons why that is so.

In the case of sentencing those who have been found guilty of committing an offence or have pleaded guilty to doing so, the business of passing sentence is a matter for judges or magistrates. They are appointed by the State government to serve in that role as part of the justice system, acting independently of the other arms of government. The notion of judicial independence is central to our democracy and a vital pillar in the maintenance of public confidence in that system.

Where a statute creates an offence, it usually stipulates the penalty in terms of the most severe penalty that may be imposed for that offence, whether it be a custodial or jail penalty or a fine or other restrictions on the offender’s liberty.

The business of sentencing is dealt with by a separate act of State Parliament, in Western Australia called the Sentencing Act 1995. It is a comprehensive statute covering all aspect of sentencing. It specifically provides that a sentence imposed on an offender must be commensurate with the seriousness of the offence.

When a judge or magistrate sentences an offender they usually do so, particularly in the case of more serious offending, with the benefit of a considerable amount of information about the offence, the victim or victims, and the offender. There will generally be submissions from lawyers for both prosecution and defence as to an appropriate sentence. There is often a pre-sentence report. There may also be a victim impact statement, medical and psychological or psychiatric reports and character references on the part of the person being sentenced. It follows that when the sentence is imposed, it is an exercise in judicial discretion in the light of all that information.

If the prosecution or the defence consider that that exercise of judicial discretion has not been properly carried out, and the sentence is too light or too great, there is provision for appeal to a higher court. The appeal court, if it considers that the sentence was manifestly inadequate or excessive, or is in error for some other reason, may quash the sentence appealed from and impose its own sentence.

The system just described works well. The number of successful appeals compared with the number of sentences imposed tends to underline that proposition. Few appeals succeed.

In recent decades there has been an increase in a legislated mechanism called mandatory sentencing. In that scenario State Parliament stipulates in legislation that, for example, for a particular offence in certain circumstances, the penalty prescribed is a set term of imprisonment which is irreducible despite whatever mitigatory factors may be present. In effect, when the Parliament enacts such provisions, it is the Parliament that imposes the penalty in advance, knowing nothing about an individual offender who later commits the offence or the. Or the circumstances in which the offence happened. The judge or magistrate tasked with the business of sentencing has no discretion but must impose the sentence prescribed by the Parliament.

In a State where there is a lamentably high proportion of Indigenous people in custody, mandatory sentencing is likely to exacerbate that situation.

Why do such provisions exist? One answer to that question lies squarely in our political process. An all too familiar part of the political cycle is the election campaign and the promises made. Law and order are one of those campaign issues which give rise to political arm wrestles as to which party is the more ‘tough on crime’. It is in that context that governments or oppositions reach for such mechanisms as mandatory sentencing and promise to create fixed sentences.

The criminal justice system in which the exercise of judicial discretion in sentencing is a vital part has widespread community support. The irresistible inference that must be drawn is that there are certain offences in certain circumstances where the judicial officers appointed by governments cannot be entrusted to exercise their judicial discretion appropriately. In that context, there will inevitably be injustices. There will inevitably be some offenders who are imprisoned who would not have been but for Parliament’s dictation. In that scenario, it is a statistical certainty that there will be, as usual, proportionately more Indigenous people in our jails. That may well mean that the incidence of Aboriginal deaths in custody will not be reduced but, rather, maintained.

It is important, in a liberal democracy such as ours, that our system of justice be independent of the elected government of the day and be seen to be so. I have no doubt that many of those offenders who find themselves in custody for an offence where a mandatory sentence is prescribed, would have been in the same situation had there been no such provision. Where a mandatory sentence is prescribed, the absence of the ability to impose a lesser sentence must mean that there will, from time to time, be injustices, in that there will be offenders in custody whose mitigating circumstances are such that, absent the mandatory provision, the offender would not be in custody. Instead, they might have received a suspended term of imprisonment or a non-custodial penalty of one sort or another, such as a fine.

Connected with all of this, too often, in the political contest, we hear the claim that crime or particular crimes are on the rise. It is true that, depending on a range of many factors the incidence of particular offences rise and fall. Unlike New South Wales, Western Australia does not have an independent body receiving and collating data in the area of criminal and traffic law. Of course, various entities such as the Police, the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Courts, all collect and retain data. What is missing is a central independent bureau charged with the responsibility of receiving, collating and publishing accurate, reliable information in such areas as the prevalence of criminal activity in particular regions and with respect to particular types of criminality. Such a body could collect, collate and publish timely information as to sentencing and its impact in particular regions and with respect to the various ethnicities that make up our State.

Again, the issue of independence is crucial. With independence comes community confidence. Such a body would, hopefully, provide light and clarity in an area where, too often, the political imperative leads to shrill and exaggerated claims about what is happening in our community and what sentencing measures are necessary to deal with crime.

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

This article was written by Philip Eaton, our Legal Correspondent