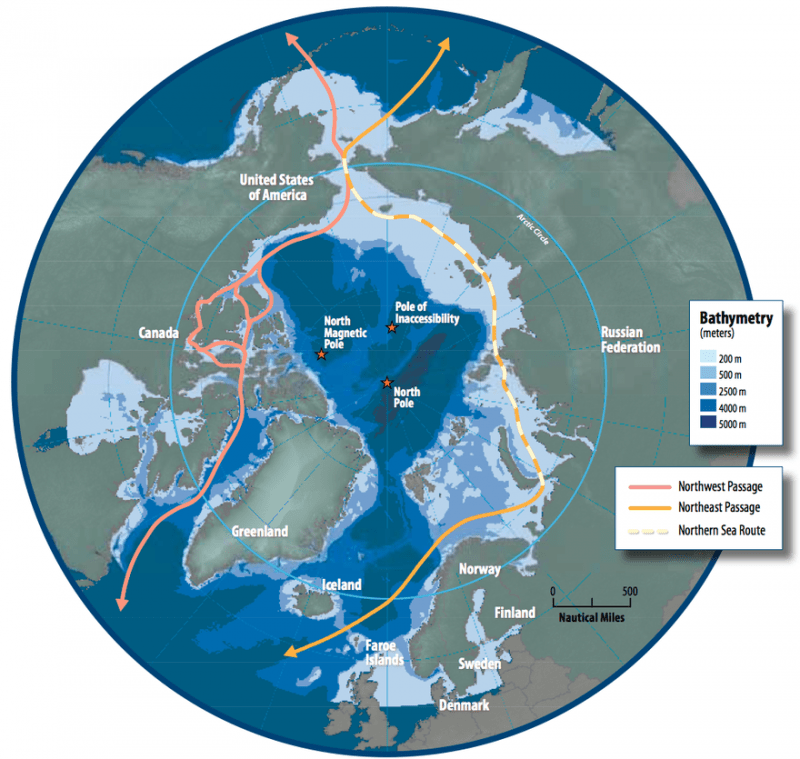

The Arctic Route

We don’t get too many (zero, to be exact), Russian ice-breakers sailing into Fremantle. However, maritime news is buzzing since a Russian LNG tanker traversed the Northern Sea Route (NSR) in January for the very first time.

The NSR is a shipping lane between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean along the Russian coast of Siberia and the Far East, crossing five Arctic Seas: the Barents Sea, the Kara Sea, the Laptev Sea, the East Siberian Sea and the Chukchi Sea. The entire route lies in Arctic waters.

Ice-breaking LNG vessel Christophe de Margerie (named for the late Total CEO who had strong ties to Russia, and who died in an aircraft accident there in 2014), took just under 11 days to sail from the Gulf of Ob’s seaway channel to Cape Dezhnev in the east – 2,474 nautical miles (4,582km). She sailed stern first for about 66% of the journey at an average speed of 9.5 knots.

Unlocking the previously perilous route promises economic potential in the Russian economic exclusion zone, with ambitions to increase traffic along the route by 90 million tonnes by 2030.

For Igor Tonkovidov, this is a century’s old Russian dream. Igor is the president and chief executive of Sovcomflot, Russia’s largest shipping company.

“The speed of voyages on the Arctic route, compared with southern transit through the Suez Canal is more cost-effective and reduces the journey’s carbon footprint by 7000 tons per round trip,” Igor said. The route is estimated to reduce delivery distance between Europe and Asia by 40%.

Sadly, melting ice-caps are the reason this route can now be opened, but the Russians are keen to pull out all stops to further ensure the route is suitable for vessels of all sizes and say they will make channels deeper and wider and provide necessary support services along the sea coast. All while Sovcomflot’s Green Charter commits to fighting climate change.

Billions of rubles are being sunk into making the NSR attractive to international markets, which currently question the route’s safety and environmental viability, especially as communication capabilities are currently dangerously limited. Launching satellites, building ice-breaking container ships, creating oil spill action plans, deepening the seabed, ensuring state of the art technology to minimise pollution, developing port structures, installing electricity, providing training and meeting a multitude of other logistical necessities, demonstrate Russia’s determination to succeed.

They are considering setting up a state-run shipping company in response to an eight-fold growth in shipping volumes over the past six years alone. Their closest trading partner, China, may cough up as the route will benefit their transport of oil and gas to Europe and Asia, but it’s Norway and Japan that have aligned closely since collaborating on the 1993 project, the International Northern Sea Route Programme, designed to shatter myths about the NSR.

Sportwear company Nike and Ocean Conservancy have joined forced to oppose the Arctic shipping route by putting pressure on the IMO – the International Maritime Organisation – to ban heavy fuel oil (HFO) in the the Arctic, which they believe is vulnerable from “risky shipping”.

Ocean Conservancy CEO, Janis Searles Jones says: “The dangers of trans-Arctic shipping routes outweigh all perceived benefits”, a belief shared by shipping giants CMA CGM, Hapag-Lloyd and MSC, who have pledged their allegiance. Those benefits aren’t just perceived however, as the shortest sea lane linking Europe and Asia suggests delirious amounts of benefit and the likes of COSCO and Oldendorff Carriers already have plans to expand their operations along the Arctic route. Many more are likely to join them.

Seafarer crisis continues

Last year, we reported on the increasing humanitarian crisis for seafarers enduring extended time at sea as the Covid prohibited ships from entering ports and made repatriation of the crews increasingly complicated. Sadly, on 28 January, 2021, a seafarer who had been onboard asphalt tanker, Sea Princess for 13 months, took his own life after UAE port state services denied the vessel entry. Repatriation of the body was eventually approved.

Closer to home, a desperate swim to shore off Albany for Vietnamese seafarer Ho Anh Dung in January, further highlighted the lengths sailors are prepared to take for their freedom. Though his motives have not been fully established, Ho was given a six months suspended sentence and will be deported from Australia to his home country. That’s one way to get repatriated.

In December 2020, the United Nations General Assembly urged all countries to designate seafarers and other maritime personnel as key workers.

And Secretary-General of the International Chamber of Shipping, Guy Platten, is imploring more countries to sign the Neptune Declaration on Seafarer Well-being and Crew Change. You can read more about the issue here.