The clamour surrounding the delivery of the verdicts in the trial of Bradley Edwards has now subsided. His was a trial by judge alone. That form of criminal trial has, historically, in Australia, been a fairly rare bird. As a matter of law, the right to trial by jury is enshrined in section 80 of the Australian Constitution and has its foundations in each State in the development of the common law.

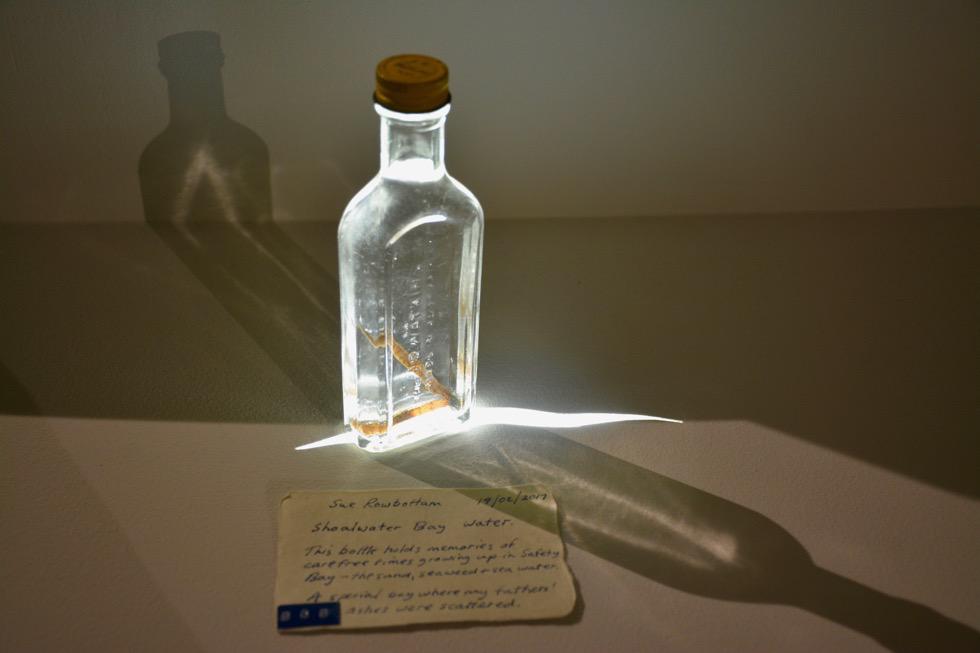

Justice Hall. Credit: ABC

In this State there is provision in the Criminal Procedure Act which allows both an accused and the State to make application to a judge for the trial in a particular matter to be by judge alone. That application must be made before the identity of the trial judge is known to the parties. High profile cases, such as that of Bradley Edwards, are often the subject of an application, usually because of the amount of publicity attracted by the case prior to and during the trial or because of the complexity of the evidence to be led, or both.

In recent times in this State there has been an increase in applications for trials by judge alone, particularly in the District Court of Western Australia because of the arrival of Covid 19. With the State in lock-down it became impossible to conduct a jury trial because courts and, in particular, court-rooms and jury boxes could not comply with the social distancing requirements. Jury trials were suspended and listings vacated. For those awaiting their trial in custody, having had bail denied or revoked, the prospect of being unable to be tried for an indefinite period was an awful and intolerable one. Trial by jury is the norm and the expectation of most awaiting trial. Rather than wait for what might be quite a long time, there was, not surprisingly an increase in applications for trial by judge alone. In the past sevral months, there has been a significant increase in trials by judge alone, trials that would have been before a jury in normal circumstances.

Trial by jury has long been the preferred option for most people facing trial on indictment throughout Australia and in many other parts of the world with criminal justice systems similar to ours. It is a system of trial that serves the community and the State well. Not only is it perceived to be the hallmark of a fair trial it is a very efficient and effective way of dealing with serious criminal matters where the plea of the accused person is one of not guilty. There is another invaluable aspect from the State’s perspective. At the conclusion of a jury trial, the jury, having heard all the evidence, the speeches of counsel and the judge’s directions as to the law, are asked a small number of very short questions at the end of their deliberations. The most important of those questions is as to whether they find the accused person guilty or not guilty. That exercise leads to the judge formally recording a judgment of conviction or acquittal, as the case may be.

Importantly, the jury are not asked to give reasons for their verdict. In the case of the trial of Bradley Edwards, the trial judge was required, as is always the case in a trial by judge alone, to give written reasons for his verdicts. Not surprisingly in that case, given the length of the trial and the complexity of some of the evidence, the trial judge adjourned the matter of verdicts for several weeks. The delivery of his verdicts and the written reasons for them was, of course, a matter of immense public interest.

Returning to the virtue of the system of trial by jury, if all trials in serious criminal matters were by judge alone, the criminal justice system, as it currently stands, would require far more resources than it has. The criminal justice system would inevitably become slower and public confidence in our institutions of justice would be eroded. While there will continue to be cases where the interests of justice require a trial by judge alone, the system of trial by jury will continue to be the preferred mode of trial in the vast majority of cases.

Here’s Justice Hall’s judgment in Western Australia v Edwards.