The Shipping News is very pleased to bring you this new feature on …The Movies, The Pictures, the Flicks, The Cinema, whatever you were brought up to call the successors to the Moving Pictures. We thought we’d coin a phrase and call them – Motion Pictures! (Yes, we know, it’s been done before.)

The idea for a feature on Motion Pictures came to the Editor of Shipping News when, for the Nth time, he found himself in a social gathering in the midst of people learned in the history of the cinema, people who not only knew the names of important French movies and directors from long ago, but who could also pronounce their titles and names, in French, with a Parisian accent, and who seemed to go all starry-eyed and gooey at the mention of old-time matinee idols, like Fred Astaire (although there is considerable debate about Fred’s standing as a matinee idol, one gathers, though much less about his dancing). At that point the editor realised he knew next to nothing about The Cinema and it was high time he learned a few rudimentary things, in order to avoid further social embarrassment.

The result is this feature, where the Naïf Editor, Michael Barker, engages in a continuing conversation – you may call it Socratic Dialogue if you like – with a local Freo Movie Buff, Anne-Marie Medcalf.

We will serialise the conversation and bring it to you weekly.

We are also pleased to encourage your involvement in our project. Don’t hesitate to supply your own answers, and questions. You can do that either directly, by emailing the Editor here, or go onto our Facebook page @fremantleshippingnews and join in the discussion.

So, let’s get underway.

Episode 1 – The Premiere Episode

Naïf – Welcome to Motion Pictures, Buff! Can I kick off this conversation by asking you this: At what age do you remember first becoming enchanted, if that’s the right word, with ‘pictures’, as we used to call them when I was a kid growing up in the West Australian wheatbelt in the late 50s; and where were you when you first became enchanted, and what was the ‘flick’, another expression we used way back then to describe a picture?

Buff – Where and when, but there is also who?

Cinema became part of my life in my childhood in Paris with regular visits at the Passy and the Alexandra Passy Cinemas near my parents’s place. But the fun, the excitement and the magic of it all penetrated by osmosis during the holidays, which we used to spend in Tunisia where my family comes from.

The inbetweener for this encounter was my father, a cinema and theatre enthusiast. In terms of cinema, I would not exactly say he was a film buff. Although a distinguished doctor and an intellectual, deep and meaningful movies were not his fare of choice. He liked westerns, thrillers and movies that pressed emotional buttons, not ashamed to have a cry at the end of most movies, and to shout his feelings in the middle of them.

And to the movies we went, me always silently hoping the film was suitable for my age and I would be taken along. The Tunisian holidays were the best time of all for it.

My grandmother’s holiday villa, which a few years before had sheltered the whole numerous family from the worst horrors of Nazi Europe, was situated in Le Kram, now returned to its proper name of El Kram ( the fig tree), a small town on the outskirts of Tunis. It was a two minutes walk from the sea and probably five from the Cinéma Le Kram.

Cinéma Le Kram was an outdoor cinéma. No, don’t think Somerville or even drive in. Beyond the small street entrance you arrived in a courtyard, bordered on two sides by low apartment buildings. The screen hid the back of some shops, if I recall rightly. The seats were hard old fashioned, green garden seats, necessitating lots of pillows to become vaguely comfortable. We were always jealous of the people in the flats above, comfortably settled for theIr free film on their balconies.

Before going in my father would buy us glibètes wrapped in a newspaper cone. Glibètes are dried and salted watermelon seeds. They keep you chewing, but they were also a favorite sport as you peeled their skins with your teeth and spat it as far as you could, on your friends, when the film was boring – and Tunisians, as courteous as they are, did not have much time for boring movies.

And then the lights were turned off. ‘It’s starting, it’s starting’, everyone would shout as if each time it was a miracle, which, thinking of it, it probably was. I still have the same emotion when a film starts. The magic never fails.

Whatever the film, it was never passive viewing. Comments, advice and warnings to the characters, hoooos when a kiss eventuated and screams at scary bits rarely stopped; mainly in Arabic, but also in Italian, Maltese or French, the other languages also heard in this then French Protectorate.

This is indeed where my father had learnt his behaviour at movies. Many years later, in 1975, I saw The Godfather Part II (1974), at the Roman amphitheatre in Carthage. And in this august setting, people were still spitting glibètes, and still shouting at the Godfather in multiple languages. Best viewing of this film I ever experienced. The thing is you actually lived the movie, you became the characters, they were real.

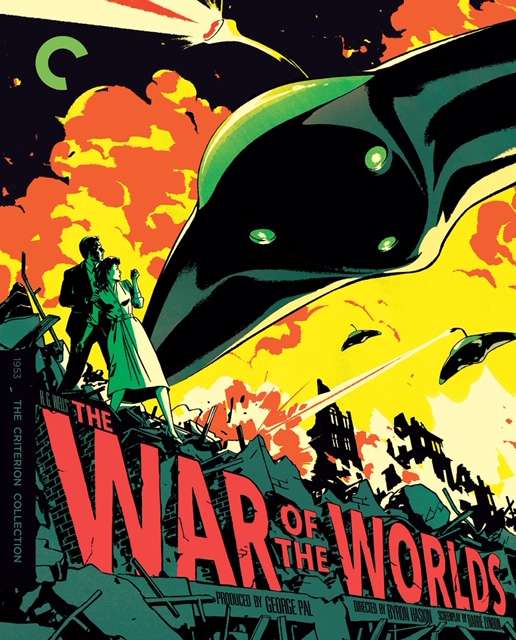

I saw many films at Le Kram and they all run a bit into each other. But the one that stands out, and encapsulated all the excitement of cinema at the time, was Byron Haskins’s The War of the World, the first film (very loose) adaptation of HG Wells’ 1897 novel of the same name, produced in 1953, fifteen years after Orson Wells’ famous and scary radio production of it.

It was probably 1954 when it arrived at the cinéma Le Kram in the middle of summer. I was ten, terrified, entranced and sold to science-fiction for ever. The war was close enough to everyone’s mind, even mine, to be put in the mood by the initial footage of all the weaponry used since World War I. The cold war analogies that run through the film bypassed me at the time, but the level of destruction wreaked by the Martians did not.

Special effects have, of course, developed a million times since then, but it all felt very real to me, more than real even: possible. No wonder the film got an academy award for special effects. It was mind boggling at the time. I must confess I would have to see it again to be able to say anything about the acting – the actors were not actors in my eyes, just people.

What stopped me having nightmares for ever after that was the two main protagonists’ love affair and their resilience and inventiveness. And of course the fact that all the Martians end up dying because they do not have any immunity against Earth’s bugs. Pandemic amongst the Martians, how timely. As an aside, when I went on Google to make sure of the date, I also noticed that the film was shot in a Californian town called Corona…

Claudia Cardinale

Oh, and I should add, the neighbouring little town from El Kram, La Goulette, known for its outdoors fish couscous restaurants, was well feted in terms of cinema too, as this is where Claudia Cardinale was born and raised, in a quite populous and boisterous area. She is known to have come back on occasion, welcome always as ‘our’ Claudia should.

Naïf. OMG, Buff, I truly had no idea that my opening roll of a little snowball question down the slope would start such an avalanche of an answer! Wow, wow, wow! Multilingual Tunisia. Audience involvement. Your father as your role model watcher. Calling out, crying at the end. I must tell my teenage granddaughters, who are always wanting to ‘Shush, Poppy!’ when we’re at the movies. So did you take on that participative role at the movies like your father, or did you also have other, less demonstrative movie-watcher role models who counselled a more demure approach to the silver screen? And returning to the shores of France, after the holidays, what was French cinema all about in those days, let’s say when you were a young woman, but not yet 18? What was your genre then? Who were the stars? Is there one movie from that time that, for whatever reason, stands out in your memory?

Buff: No, of course! Back in France there was no shouting or participating in the movies. You did not need any role model to tell you that, it was pretty obvious, especially in the arthouse cinemas that were flourishing early on. Contrary to what people often think the French are not that demonstrative.

Jean-Pierre Melville

From the time of my childhood to the times of my teens, both my tastes, following the changes in French cinema, moved along quite a bit, although, in the same way as post-modernism was largely built as an inevitable offshoot of modernism, so was the New Wave developed on the back of the celebrated classical French cinema, mainly after 1960. Directors like Jean-Pierre Melville (Les enfants terribles, 1950; Le samourai, 1967, for instance) providing a hinge between the two, so to speak, and influencing generations of European, US and Asian film makers.

Among some of the magnificent classical French post-war films, Jacques Becker’s Casque d’or, his masterpiece (1952), and its ill-fated story set amongst workers and the underground, remais my favourite. It is spare as well as romantic, with magnificent photography, and is set alight by Simone Signoret’s performance.

Casque d’or

But big block busters also had their appeal. One childhood film that immediately come to mind and that I saw in Paris is an American movie, Cecil B.de Mille’s The Ten Commandments (1956), in wide screen and technicolor. A feast of noise, special effects, smoke and mirrors. It was so long it had an intermission, with a live pianist filling the time and the ushers selling ‘bonbons, caramels, eskimos, chocolats’ in a tray hanging from their shoulders. It got a couple of academy awards for sound and visual effects for its trouble. But I saw it again recently and it is now virtually unwatchable, Charlton Heston’s hairdo providing a troublesome distraction and my sympathies going rather to the hapless and beskirted Yul Brynner‘s pharaoh.

Yul Brynner and Anne Baxter in The Ten Commandments

Otto Preminger’ Exodus (1962), drawn from Leon Uris’ novel of the same name was a film which stirred the emotions and imagination of teenagers like me, fed as we were, with memories of the second World War atrocities. It is the story, drawn from a real post war event, of more than 4000 refugees, holocaust survivors, smuggled in spite of the British authorities, on a leaky, stolen boat to what was then the Palestine British Mandate. Beyond, to my mind, its debatable position on the Arab-Israeli conflict, its story, carried by a fantastic cast and Dalton Trumbo’s screenplay, is still very much one for our time.

I saw it at its premiere in Paris. It was a fundraising for a Jewish women’s organisation and Paul Newman, its star, attended.

This is still up there for me with the day long ago when I was married to an antique dealer and we sold a table to Gregory Peck, a man even more impressive in reality than in his films.

But whilst American movies were very much on our horizon at the time – the westerns of course, but also for instance the now classical musical comedies and the cult films of the Marx brothers, mimicked ad infinitum with my friends – French movies were a staple, as well as French actors. Those had very often been theatre actors in the first place and pursued both careers at the same time. As a result their performances in both theatre, where we often went, and cinema were seen in a rich continuum.

This struck home for me quite recently when one of France’s longest acting and best actors, Michel Piccoli, died. Anglo-Saxon newspapers on the whole did not breathe a word of his immense theatre career. This made for much distorted obituaries.

In terms of actors, Gérard Philipe was my all times favourite and I can still hear his slightly metallic voice. Two of his performances remained in my young memory for a long time. One was as Don Rodrigue in Corneille’s Le Cid at the theatre, and the other as the rascal, Fanfan, in Fanfan la Tulipe (1951), a sword and dagger romp with a difference directed by Christian-Jaque. It was good enough to win the Cannes best director award and the Berlin Silver Bear in 1952. But who can forget him in his many other films, all showcases of the French cinema of the late 40’s and the 50´s and of directors such as René Clair, Max Ophüls, Jacques Becker, Yves Allégret or Claude Autant-Lara to name a few. (When Gérard Philippe prematurely died, my friends and I hid in the coats in the vestiary of my school to cry.)

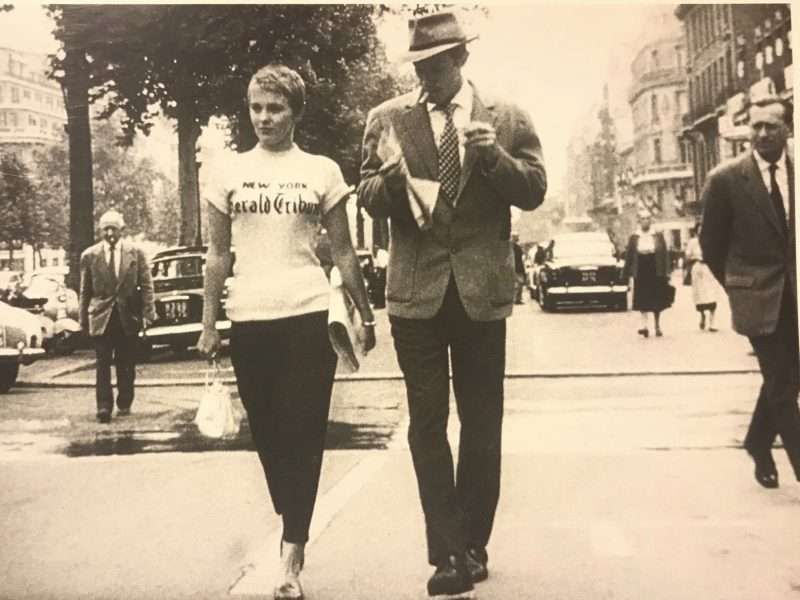

The male actors who succeeded Gérard Philippe’s generation, often as part of the French New Wave, like Maurice Ronet, Alain Delon, Jean-Paul Belmondo, and Jean-Louis Trintignant, to name a few, were no less talented and dazzling, while its actresses, Stéphane Audrant, Jeanne Moreau, Anna Karina, Jean Seberg, Bernadette Lafont and others provided, through their already subversive characters, new and sometimes puzzling role models.

Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo

But the New Wave is another adventure.