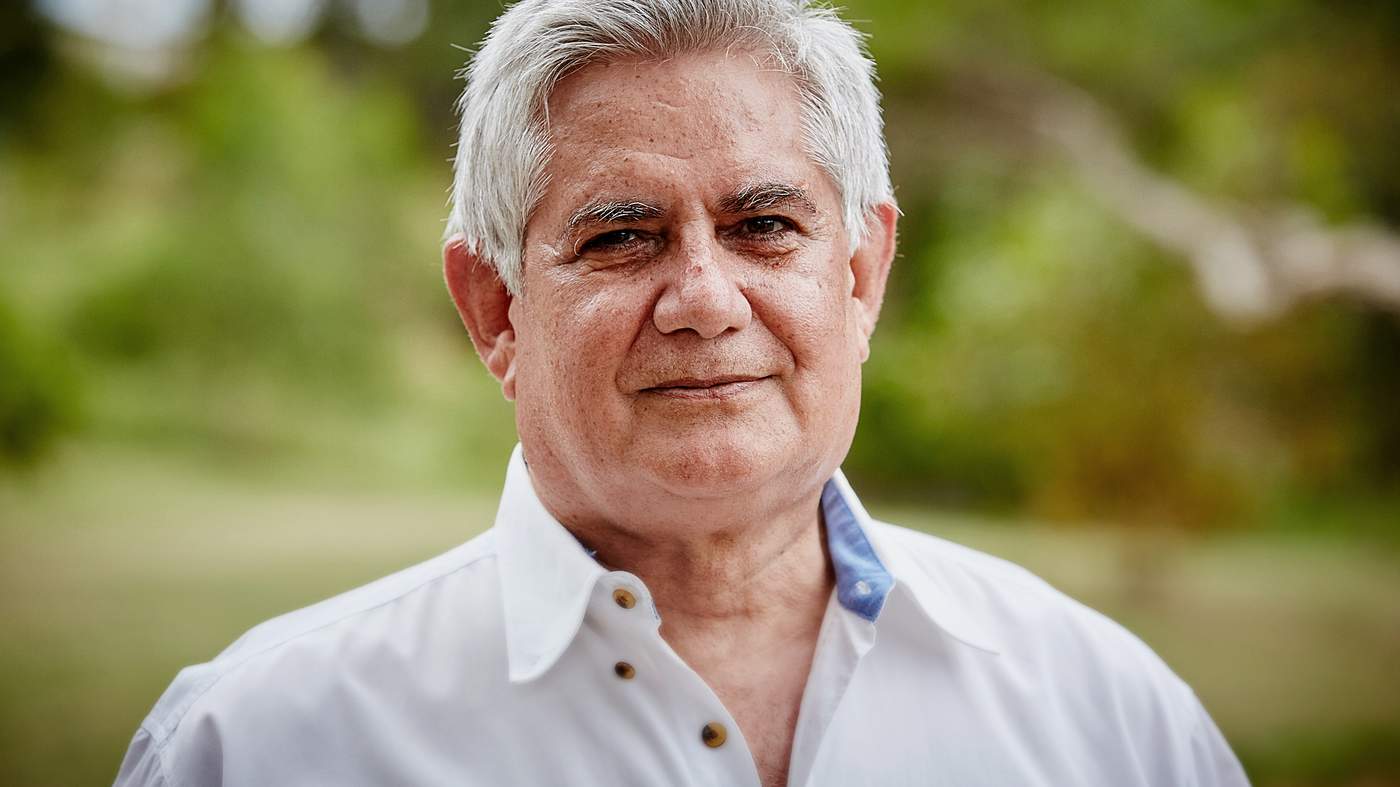

The Hon Ken Wyatt AM MP is the Commonwealth Minister for Indigenous Australians, the first Indigenous Australian to hold this important office. He is also a Western Australian, a Noongar, Wongi and Yamatji man, and the Member for Hasluck.

Mr Wyatt recently delivered the 2019 Vincent Lingiari Memorial Lecture in Darwin in which he addressed the need to look forward and work towards realising –

Local truth-telling;

Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians;

Giving voice to our local communities; and

Addressing disadvantage in Indigenous Australia.

His aim as he explained, is ‘to shift the pendulum’.

One can imagine there wasn’t a sound in the audience when Mr Wyatt delivered the lecture. Each word will have been heard. Each thought allowed to linger.

Too often, politicians’ addresses don’t have a life far beyond the moment they were made, and many hardly need memorialising. We think it would be a great pity, however, if Mr Wyatt’s Vincent Lingiari Memorial Lecture didn’t reach a wider audience, didn’t have a life of its own.

Here it is in full.

Mr Ken Wyatt:

‘Kaya wangju – hello and welcome, in Noongar.

As a Noongar, Wongi and Yamatji man standing before you, I thank Bilawara for her warm welcome this evening.

I formally acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land on which we stand, the Larrakia people, and pay, my respects to Elders past, present and emerging.

Good evening to all of you who have joined us this evening and in particular, I want to acknowledge my brothers and sisters who, many that I’ve walked, the challenges of change with.

The words of a song that was sung by the much-loved Slim Dusty of Looking Back and Looking Forward was the basis for what I wanted to cover tonight because of several reasons but Slim in particular was loved by Indigenous Australians – Slim was a storyteller.

Since the beginning of our time our nation’s sacred knowledge and identity has been kept and shared in song and in transmission through our stories.

Song is important to our culture, and to Australian culture. Music and the stories presented through songs are understood and loved by all Australians.

In Slim’s case, his songs were heard drifting throughout Australia’s living rooms, pubs, town halls, on the old wireless radio and through the records we played.

Through his songs and storytelling, Slim brought Indigenous Australia into suburbia, into the minds and hearts of the nation and the wider Australian culture.

The words you would’ve heard in his song ‘Looking Forward, Looking Back’ – are very poignant – and help paint an image of modern-day Australia.

I won’t sing it to you, because that’ll sort of distract from the quality of the music, but as Slim says:

Looking Forward, Looking Back.

We’ve come a long way down the track.

We’ve got a long way left to go.

Indigenous Australians, in everything we do, draw on the insights of our journey, the knowledge and wisdom of the past, and use that to embrace our future generations.

As we look back, we see the tracks of those who’ve walked before us.

For each of us, looking back evokes different memories and experiences, but I want us to be able to Look Forward – together – with a united purpose and determination for our children and grandchildren. And whilst for us as well – we have lived our time.

That’s why I’m here, with you, at the 19th annual Lingiari Lecture.

Tonight I will outline how I see us walking together, to advance:

Local truth-telling;

Constitution Recognition of Indigenous Australians;

Giving voice to local communities; and

Addressing disadvantage in Indigenous Australia.

So why did I start with Slim?

I’m told that, back in the day, there were juke-boxes here in the Territory that had nothing but Slim Dusty records on them. And as a Slim Dusty and Country Western music fan, I can certainly understand that sentiment.

But the thing that I really admired about him was that he sang about the land, about country, about people and our Australian way of life.

He sang about us, and to us, travelling in the old purple with his caravan to many remote communities and country towns across Australia.

Slim once said the most valuable performance fee he ever received in his entire career was the fee paid by a young girl called Miriam from Daly River here in the Territory.

Miriam and the children of the Daly River Mission wanted to see Slim perform but they couldn’t travel to Darwin to see him.

So together they saved up some money and wrote to Slim offering him an attractive performance fee if he came to their town.

The performance fee they offered was five dollars. But that was good enough for Slim.

He came to Daly, accepted the fee, and put on a show.

Over the course of his life, he visited that community many times. He’d go out to the mustering camp for dinner and share their black tea and bully beef sandwiches.

He’d watch and learn as the women and children showed him how to look for minnamindi.

He learnt how to cook with the honey-bag the kids brought back from the wild bees.

He fished with them; he went shooting with them.

He was invited to corroborees and learned how to make ochre paint.

Knowing us – and really knowing us – meant he could sing about us. He could share our stories in ways we didn’t have the means to and he could tell us stories of other places and people that helped us to understand our neighbours around us.

He sang of Trumby the ringer who couldn’t read or write…he sang of The Tall Dark Man in the Saddle…and of the painter Albert Namatjira.

He sang of a man called Bundawaal, “a King without subjects or crown”; a tribal elder reflecting on past struggles and glories, who couldn’t stop “an alien race without pity or grace” eradicating his people.

The song was based on a story that the local Aboriginal people told Slim while he was on tour.

He was singing about this when hardly anyone else in Australia was talking about us in the same way that he sang.

Slim opened the door for Indigenous people themselves to share the stage in the Australian country music industry, some of these early Indigenous pioneers in the Country Music Industry were people like Auriel Andrew, Jimmy Little and Gus Williams, just to name a few.

Picture a time in Australia, and this is for all the young ones out there, because for many of us here tonight know what it’s like to be told:

Where we could – and could not – sit.

Where we could – and could not – go.

You couldn’t sit on a seat at the cinema – you had to sit on a milk crate at the front of the auditorium or the old chairs.

You couldn’t enter a pub.

But Slim Dusty’s concerts were open to all, and we could sit wherever we liked.

People like Slim helped shift the pendulum.

Throughout our history, advancements in Indigenous affairs have swung like a pendulum.

This pendulum has shifted, back and forth, sometimes bringing meaningful advancement for Indigenous Australians, through events and actions of our own people, such as:

Albert Namatjira becoming the first Indigenous Australian to be given restricted citizenship,

Charlie Perkins Freedom Ride,

The election of Neville Bonner in 1971 to our nation’s Parliament, the first Indigenous Australian to serve in the Australian parliament. If you ever get the opportunity, go to the old museum at the parliament, the Old Parliament, and read his diary entry. He has a pillow on display and the diary entry says “I was never invited to any event, any function. At the end of a day, I would leave my office, go home to my trusted friend, my pillow, and would lay my head down to rest.”

Eddie Mabo’s fight and victory for Native Title and land rights, and of course

Vincent Lingiari’s Wave Hill walk-off and a strike which led to the Native Land Rights Act in 1976.

These significant achievements shifted the pendulum positively, however this hasn’t always meant the pendulum stayed that way.

While we have succeeded in some areas, in others we have not.

Looking forward, we must address where we have failed.

Where we have failed to permanently shift the pendulum on fundamental disadvantage with Indigenous Australia, on factors such as;

The basic right to an education,

The value of a full-time job,

Access uniformly to health care – and the need to address alarming rates of suicide and mental illness in our community,

And much, much more.

As I stand here tonight, looking forward, I am optimistic about the opportunities that lie ahead for us – and equally as realistic about the challenges we must overcome.

LOCAL TRUTH-TELLING

As we embark on this journey – I am above all else wanting to have and encourage conversations across this nation – through these conversations we become more comfortable with each other, our shared past, present and future.

Truth-telling to me is not a contest of histories; it’s an understanding of history. It’s an acceptance that there can be shared stories around events in our nation’s history.

I recently spoke with an elderly woman who expressed her dismay that her childhood and education hadn’t featured the stories or history of Indigenous Australians.

In particular, she spoke about learning of massacres later in life and used the words to say that she had been lied to as a child.

I responded by saying that she wasn’t lied to, but she didn’t hear or have the opportunity to hear about our history through our eyes.

This is why we share and we need to share our history because it is important that the history of this nation is paralleled to the events that have occurred.

It is not about guilt. It is about acknowledging that there were events that occurred.

And we need to acknowledge that people will come to this debate from various angles, and perceptions of history – none of this is wrong, or should be dismissed or discouraged.

We cannot simply tell our truth through yelling.

It must be done through conversation.

For me, one of the most indelible moments that sparked a national conversation was that in December 1992 when the then Prime Minister Paul Keating delivered, what is now known as the Redfern Speech.

I had the fortune of being there.

The crowd was electrified and noisy, charged with energy and emotion.

I remember a bunch of balloons in the colours of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags bobbed on the roof above Keating’s head, and children dressed in red as they sat on the grass at the foot of the stage, trying to keep still but mostly failing.

Keating’s words that day have entered the history books, so has that speech.

The words most often quoted are his accounting of the deeds of non-Aboriginal Australians. He said:

“We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life. We brought the diseases. The alcohol. We committed the murders.”

But it was the next line that caused the strongest reaction from the audience. You couldn’t miss it.

“We took the children from their mothers.”

Those seven words drew a loud outburst from the crowd.

It was raw emotion.

Yet, it was both positive and negative – but most of all it was a significant moment of truth-telling, by none other than our nation’s Prime Minister of the day.

That shifted the pendulum – and from that shift, in 2008 we saw Prime Minister Kevin Rudd issue an apology on behalf of the Commonwealth Government to the Stolen Generations.

And any one of us here tonight could probably remember where we were, who we were with and the way in which we watched that speech being delivered. But the reactions that were portrayed on the screens, the tears running down the faces of those who were most affected, and the sense of relief became a glaringly obvious moment based on the fact: the truth of the past had been acknowledged.

Whilst this was regarded by some as merely a symbolic gesture, as of 2015 the fact is that there are an estimated 13,800 surviving Indigenous Australians aged 50 and over who had been removed from their families and communities and considered part of the Stolen Generation.

The healing that resulted from this act of truth-telling cannot be quantified.

And while this took time, it does demonstrate that truth-telling today can lead to significant moments of reconciliation in the future.

If we walk together and acknowledge our shared history we can achieve permanent positive change.

Truth-telling is not best served by a national commission or similar interrogation of truth.

We all should know detailed stories of the areas in which we lived. All Australians – sharing the one history.

I personally would rather see an organic and evolving truth-telling, in which we share our stories, our acknowledgement of the events of the past, but the way in which we as a nation of people are melding together for a better future.

There has to be local storytelling of the history of the past. And it must be local, otherwise we gloss over those very elements that are important in country, within region, and we will only tend to focus on national stories.

Every story to do with our country is as equally important as the national stories.

Around kitchen tables, over the BBQ and in the backyard, down at the local football and netball clubs and in pubs – this is where permanent change will come from – not from loud voices in Canberra and the media.

The 2018 Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition heard this first hand, and reported the following:

“A large number of stakeholders agreed that truth-telling is best implemented at local and regional levels.”

A key component of this local truth-telling is the fact that we must be comfortable having these conversations.

And comfortability is a two way street – for Indigenous Australians it means having the ability to speak our truth and have it heard; and for those seeking to understand, we must allow them to ask questions and contribute to the rigour of the conversation – whilst at all times maintaining respect for one another.

Until this happens, we won’t see the shift in the pendulum that we want to see and achieve.

Importantly, truth-telling is also an opportunity to celebrate the achievements of Indigenous Australians – we must stand proud and celebrate the progress we’ve made.

Too often the pictures painted are that of setback and failure, which simply reinforces the negative elements of our history.

I want us to lead in a positive manner – I want all of us to lead in a positive manner. And, I want to celebrate our successes and champion those who achieve and do great things. In sport we do that exceptionally well – we acknowledge Ash Barty, we acknowledge Cathy Freeman, and many of our high-level achieving sports men and women.

But we also need to do it for the things that we achieve personally, those matters that we achieve as a community, but as equally important is the success of a child at each stage of schooling. And I’m not talking about achieving significant reform here, which is certainly important.

What I’m referring to is the kid who didn’t finish school getting their first job, and keeping it, and finding themselves contributing member to their community.

We need to celebrate every child who goes to school and receives an education, the foundation of a more meaningful and purposeful life.

These quiet achievements are as much about what defines Indigenous Australia in 2019 as the differences, we all too often allow those differences to divide us.

CONSTITUTIONAL RECOGNITION OF INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS

Looking forward to our opportunity to shift the pendulum – let’s talk about Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians.

Whilst the Constitution belongs to all Australians, it is important for the purpose of the conversations that I’ve spoken about tonight are so critical in achieving what we set out to do.

As I’ve said before – this is too important to rush, and it’s too important to get wrong.

On eight occasions, the Australian people have voted to change our founding document.

The Constitution is like the rule book for sport; it is the rule book of our nation.

On 36 other occasions they’ve been lost – and there 36 issues that have not come back to the Australian people to consider again in a referendum.

The most recent example of this being the 1999 Republic and Preamble Referendum – a campaign that saw a rift in our nation’s fabric – and result where not a single State carried a Yes vote – and often forgotten, is the fact that the vote on the Preamble was rejected by a greater margin than the question of the Republic.

This is not to say we can’t achieve Constitutional Recognition within the term of this Parliament.

But it is important that we learn from the 1999 Referendum, and reflect on how challenging it can be to translate good will into a positive outcome.

Looking back to 1967, and the Referendum put forward by the Coalition Holt Government, 90.77% of Australians voted to embrace our people as part of Australia.

Key to this was bi-partisan support, the simplicity of the question and a clear purpose for holding the Referendum.

I want to be very clear – the question we put to the Australian people will not result in what some desire, and that is a enshrined voice to the Parliament – on these two matters, whilst related, need to be treated separately.

This is about recognising Indigenous Australians on our Birth Certificate.

And I’ll talk about voice later on.

When I was elected in 2010, I was appointed to the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians – we held public conversations in 84 urban, regional and remote locations and in every capital city – as well as the hundreds of meetings and around 3,500 submissions were received.

From this, the Panel reported to government in 2012, and subsequently we had three more reports to government on the same matter.

Each of these reports have looked at a set of words to put to the Australian people.

The words are there in those documents.

Our challenge now is finding a way forward that will result in the majority of Australians, in the majority of states, overwhelmingly supporting Constitutional Recognition. We must be pragmatic.

The Constitution belongs to all Australians, from those in Slim’s home town of Kempsey to those in my childhood town of Corrigin, no one of us can lay claim to the Constitution.

It belongs to us collectively, and it belongs to those who came before us, and most importantly, it will belong to our children and our grandchildren.

I’m not thinking about what I can achieve for myself, or concerned about my legacy, I’m focused on realising recognition for my children, your children and generations to come.

Let me challenge the loudest voices in this debate – now is our opportunity to do this, and it will require understanding and tolerance of all views.

If we don’t seize the opportunity now, it may be lost for all of time – we must not allow this to happen – so I invite you to walk with all Australians on this journey.

It’s not about walking with me, or walking the path of any one individual – it’s about walking in the footsteps of those who’ve come before us, to create a new path for all Australians.

This is not an issue that can be viewed through the prism of political ideologies and all Australian politics have a way to go.

I ask my colleagues, from all sides, to remember what is your first duty as a Member of Parliament – and that is to listen to and represent the views of your community.

There is a lot of work to do on this journey – we haven’t had a referendum since 1999 – and we must educate a new generation on the importance of the Constitution and the significance of the change we are asking for.

This will require all of us to lay the foundation through education and conversation – that is the first step.

I had a young Australian ask me the other day when to expect their ballot to arrive in the mail to post back and wanted to be part of this change.

I had to explain to her the difference between the recent postal plebiscite to recognise same-sex Marriage and the difference between what a referendum is and how it works.

Having these conversations are as important as the conversations we have about why we need to recognise Indigenous Australians in the Constitution and demonstrates the steps we need to consider to achieve this.

Let’s start these conversations, which may seem very basic to us, but are very important to realising success.

The pendulum will shift – but it’s up to us to determine which way.

VOICE

Let me now turn to voice and being heard.

Having your voice heard is going to look very different to how your neighbour sees their voice being heard.

In Australia today, there are almost 800,000 Indigenous voices – all of equal importance and relevance.

Therein lies the complexity of defining ‘a voice’.

The voice is multi-layered and multi-dimensional.

I see rooted in our elders, who are the basis for our knowledge, culture and lore, and rooted in our communities, and extending through the ways in which all levels of government, service providers and corporations engage and work with our people.

Too often I visit communities and I’m told that their voice isn’t being heard because needs are not being met on the ground and we certainly heard that at Garma for those who were in attendance.

And others, who say that they want their local member of parliament to hear their voice.

How we give voice to these Australians is through conversation and understanding.

Knowing what is happening, knowing what needs to happen – and work with leaders and individuals within our communities to develop the practical solutions that see a shift in the pendulum at the most local of levels.

Having these voices heard is not only a matter for the Commonwealth government – it’s a matter for State and Territories, local governments and service providers.

That’s why I’ve tasked the National Indigenous Australians Agency with changing the way they engage – to ensure that the priority is meeting the needs of local communities first.

I’m often asked about the commitment of the Morrison Government but let me assure you that the Morrison Government is committed to a co-design process so we ensure we have the best possible framework in place to hear those voices at the local, regional and national level.

More will be said in the months to come, and much like Constitutional Recognition, it’s too important to rush, or to get wrong.

This is about ensuring Indigenous voices are heard as loudly as any other Australian voice is.

Again – this is a journey for all Australians to walk, and through conversations we must respect, understand and address all perspectives on this matter.

Giving voice to Indigenous Australians, and realising Constitutional Recognition are the greatest opportunities in our lifetime, but they are not mutually-exclusive.

This must be remembered if we are to shift the pendulum.

SHIFTING THE PENDULUM

But what about shifting the pendulum tomorrow?

There are things that we can be doing, as individuals, as parts of organisations and as members of communities to positively shift the pendulum.

Don’t think that any one action you can take won’t lead to meaningful change – the individual actions of those here tonight, let alone all those across this nation, has the potential to improve lives and outcomes for our people.

We can all shift the pendulum.

And that’s what I’m focused on every single day.

I will be judged as equally on my ability and this government’s ability to create jobs, improve access to healthcare, have young people attend school and succeed, and reduce suicide rates as I will be on delivering Constitutional Recognition.

And this is what drives me.

Every Indigenous Australian who finds a job, every young person that gets to school in the morning, every prevented suicide and instances of Otitis Media for example being treated is what I will celebrate.

And that’s something you should celebrate too. It’s something you can have a direct impact upon.

How do you play a role in shifting the pendulum? Consider that proposition tonight and leave here motivated to shift the pendulum for one person, one family, one community or more.

Many of you will be doing that already, so the question becomes, how can we grow and share that? How can we celebrate that?

We must look at what we do and the good we have the potential for – and to then share these successes as loudly and widely as possible.

By celebrating success, we’re not blinding ourselves to the challenges at hand, or dismissing the levels of disadvantage within Australian Indigenous communities.

We know that people are dying earlier.

We know that our people are committing suicide.

We know that children are being born into a lifetime of poverty.

And, that’s on us as well.

I don’t discount or diminish this in any way.

We owe it to our children, and to future generations to come to create an environment and culture of opportunity and of positivity so that when an Indigenous Australian children is born, they see a world where their dreams can be realised, and where each day is filled with hope and optimism.

Where the face they see in the mirror, doesn’t limit their aspirations.

Where the face they see in the mirror is the face they see reading the 5 o’clock news, the face they see exploring space or one day the face they see leading our nation.

To achieve this future, we must change how we look at ourselves – and we must have others view Indigenous Australians through our successes and not our failings.

Just as disadvantage should not be viewed through colour – success should not be limited by colour.

I asked what we can do tomorrow to shift the pendulum – well, start by celebrating success, by sharing success and by ensuring that one person’s success today is the hope for someone else’s success tomorrow.

But to emphasise the importance of acting and listening at a local level, I want to take us back to the 1967 referendum.

As the referendum votes were being tallied and the nation’s ‘Yes’ vote was starting to emerge, Vincent Lingiari, a Gurindji man and his stockmen were several months into their famous Wave Hill walk-off and strike.

The strike although initially an employee rights action had soon become a national issue as the relationship between Indigenous Australians and the wider community and our national idioms were once again being challenged.

The strike lasted 8 years and that eventually led to the Native Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976.

This shifted the pendulum, legislating the right for Indigenous people of the Northern Territory to negotiate over any developments on their lands.

LINGIARI

Lingiari’s actions at a local level, culminated in the Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s pouring the red dirt of our land through the hands of Vincent.

While this act was symbolic, it put in train a series of events that defines the land rights movement to this day.

The courage shown by Lingiari was not only for him, but for future generations, as recognised by what Whitlam said. And I won’t repeat what Sue shared with us earlier but it was a sign of possession of our lands for our children forever.

I am truly humbled to be here in front of you, delivering the 19th annual Vincent Lingiari Memorial Lecture – and I thank Charles Darwin University for the opportunity to contribute to this series of lectures, which has helped in its own way, be a form of truth-telling and spark the conversations that we’ve needed since 1996.

To be in the company of such distinguished voices truly is an honour.

And, I don’t want tonight to be about me, but if I could take one moment to say that the significance of being appointed the first Indigenous Minister for Indigenous Australians is not lost on me.

And I thanks the Gurindji people for their faith and for their commitment and I will certainly walk with you to deliver on the things that are important to our people but I will walk with our people across this nation and other Australians.

For young Indigenous Australians out there, across this great nation, dreaming of a career in politics, I hope that my journey can give you hope.

Many of you here know my journey, but just let me share it again for that young person who’s hearing from me for the first time tonight.

I was born in 1952 and raised in Roelands Mission near Bunbury in Western Australia, and the oldest of 10 kids.

My father was a railway ganger. My mother was a member of the Stolen Generations.

And, we lived in a tiny place called Nannine, just west of Meekatharra.

My schooling at first was by correspondence – working a radio with a foot pedal, like an old sewing machine, for two hours at a time.

Soon afterwards, my parents moved to Corrigin.

Education was my turning point, and by going to school, my drive for knowledge and desire to learn is something that I retain and value today.

I have a few other fragments of memory from when I was a skinny-ankled kid running around Corrigin.

There was the time that some people in our town started circulating a petition to get the Aboriginal family that had just moved in kicked out.

The petition failed. The townspeople wanted us to stay and have a fair go.

I also remember a time when I was about ten years old and somebody said to me: you might end up being a politician one day.

And I thought “not in this country will I ever have that opportunity”.

As I grew into a teenager in the mid-60s, I became enterprising.

I worked on farms, I’d catch rabbits, sell the meat to the butcher (certainly not the ones I bruised; I’d cook those) and I’d sell the skins as well.

I used to work on farms too. I’d earn money by chopping wood, doing the fencing, driving tractors during harvesting.

But, it gave me money for myself. I’d keep half my earnings and buy a few things and put some away in the bank. The other half I’d give to mother to help put food on the table for all of us.

This is not a sob story.

To me it sort of felt like freedom.

It gave me a sense of personal responsibility and an attitude of enterprising thinking.

Those experiences living in a country town probably shaped me.

While I was busy skinning rabbits and making a buck, Australia was growing and changing.

I hope collectively we can fulfil the expectation I feel each day, to continue to grow and shape a better future for all Indigenous Australians, and continue the healing of our nation.

I know I don’t walk alone – but I also acknowledge there are many expectations placed on me. And I feel the weight of expectation.

But, I want to take this weight – and turn it into an optimism for what we can achieve – together when we swing the pendulum.

CONCLUSION

And, I’ll repeat again – everything I have spoken about tonight, from truth-telling to Constitutional Recognition is too important to rush, and too important to get wrong.

I need everyone in this room, and all of those out there who want us to succeed to ask yourselves – what can I do to help us realise our goals?

What are you going to do to shift that pendulum?

What are you going to do tomorrow, in three months’ time and in a year’s time? – good will, while important, will not allow us to complete this journey and positively shift the pendulum.

How can we elevate our successes?

How can we give voice to those who feel voiceless?

And, how can we make sure their voices are heard as loudly as those who come from Canberra and in the media?

I want you to remember these words from Vincent Lingiari:

“Let us live happily together as mates, let us not make it hard for each other… We want to live in a better way together, Aboriginals and white men, let us not fight over anything, let us be mates.”

Let this be the basis for conversations we have. And, remember these important words of Vincent Lingiari.

Take stock every so often and ask yourself – are your actions working for or against shifting the pendulum – on any of the measures we’ve discussed tonight, or on any other significant measures through which we define success and progress.

Let’s remember the importance of learning, listening and understanding when we look back – and through this, we will be able to look forward.

Look forward and work towards realising

Local truth-telling;

Constitution Recognition of Indigenous Australians;

Giving voice to our local communities; and

Addressing disadvantage in Indigenous Australia.

Together we can shift the pendulum, help every child out there realise their dreams, and leave a more unified, understanding and tolerant Australia for the generations to come.

Success for me, will be to look back, after all is said and done, and be able to say, as Slim once sang:

We’ve done us proud.

To come this far,

Down through the years,

To where we are,

Side by side,

Hand in hand,

We’ve lived and died for this great land,

We’ve done us proud.

Let us walk together.

Let us shift the pendulum together.

I thank you for the privilege of being here with you this evening.

Thank you.’