Many Australians are appalled by Trump’s anti-immigration policies. We squirm when we see uniformed immigration officials raiding farms and factories. When we hear that they are grabbing people who have lived in the community for decades and dragging them off to secret locations, most of us are deeply uncomfortable. Thank God that is not here.

A couple of times a week when I open my laptop to meet with my refugee friends in Indonesia, I am reminded of our own hidden humanitarian disgrace. Australia has collaborated with the government of Indonesia since 2001 to prevent refugees and asylum seekers travelling here by boat. As a result, Indonesia hosts around 14,000 refugees. Indonesia is not a signatory to the UN Convention on Refugees and so allows these people to exist there without the rights to work or education. In some parts of the country they are also restricted from driving a vehicle and they are not permitted to have a bank account. Access to health care is poor. Most live in dire poverty. About half are Hazara people, a persecuted Afghani minority, many of whom fled in 2013 when the Taliban rose to power.

Since 2000 Australia has had a Regional Cooperation Agreement with Indonesia. Hundreds of millions of Australian dollars have been spent through the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Initially this money funded 33 detention centers in Indonesia where people seeking asylum were warehoused, often in squalid overcrowded conditions, for years. Most of these were closed by 2018 after the Australian government reduced its funding for detention there. Australian dollars continue to flow in payments to Indonesia to fund the interception of asylum seekers, to maintain the IOM run shelters and to provide a small stipend to some refugees. Some live in the community but in the absence of a legal right to work, life is exceptionally difficult.

My friends cannot safely return to Afghanistan under its current regime. They must wait in Indonesia in the hope of resettlement to a third country. In recent times that hope has dwindled. The reality is that very few will be offered such a pathway. Australia has a policy that any refugee who registered with the UNHCR after July 2014 will never be resettled here. They are in a limbo of indefinite waiting and forced inactivity. This is piled on top of the traumas they have fled and the trauma of years of detention. They try to keep depression at bay by learning English, being physically active and through a sense of community among themselves. The mothers I speak with are focused on their children. It must be heartbreaking to see these children growing up without prospects of resettlement to a third country or the possibility of becoming a part of Indonesian society.

We must not forget these people. In keeping with principles of international refugee protection frameworks, Australia must share the responsibility for a long-term solution. A part of the solution should be to increase in our humanitarian intake, with priority given to these refugees, including those who arrived in Indonesia after June 2014.

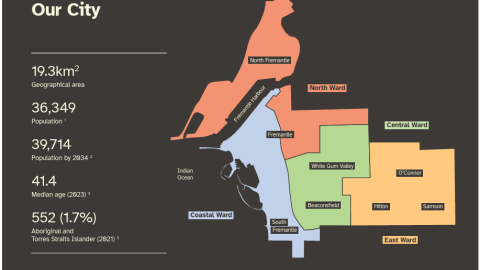

Grandmothers for Refugees Fremantle calls on our government to find a durable solution, one that provides fundamental human rights and leads to the lives of dignity and purpose which these people desperately seek.

By Pauline Pannell for Grandmothers for Refugees Fremantle

Grandmothers for Refugees

~ If you’d like to COMMENT on this or any of our stories, don’t hesitate to email our Editor.

~ WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

~ Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!