A long line of tuart trees sway to the unseen choreography of a fresh south-westerly blowing across Wadjemup, or Rottnest, as the land of spirits across the sea came to be called in more recent times.

Their roots wind into the ground in ropey knots. They entwine their way through the unmarked graves of hundreds of boys and men buried in this place, a field that has sown great distress, anguish and devastation across Western Australia for almost two centuries.

Their bodies here have never been properly laid to rest. Their spirits have remained homeless. Torn from their families in the Kimberley, Pilbara, Murchison and elsewhere, they were marched in chains away from their Country and incarcerated here in deplorable conditions, never to return.

The spirits of those men and boys – as old as 80 and as young as seven – now exist up in the windswept trees as their very DNA has been taken up through the roots, senior Noongar cultural leader Richard Walley notes with a poetic poignancy.

Richard Walley and Herbert Bropho at Burial Ground. Credit Philip Gostelow

They will remain interred here, far from home forever. The tuarts – as beautiful as they may be – are not native to Wadjemup. They never should have been planted here in the 1930s, especially on this spot, the Aboriginal Burial Ground next to the old prison known as The Quod.

The trees’ invasive root systems have now overtaken the remains to such an extent that these ancestors – these leaders, senior law men, warriors, fathers, sons and brothers – can never be physically laid to rest by their families.

Now their spirits finally will be provided a pathway to guide them home through a special ceremonial gathering of hundreds of Aboriginal people from communities around Western Australia over the next week.

L-R Richard Walley, Farley Garlett, Neville Collard, Herbert Bropho. Credit Philip Gostelow

“Those men and boys have not been laid to rest,” says Whadjuk Noongar elder Farley Garlett, a core member of the Aboriginal-led Wadjemup Project.

“They’re not on Country, they are in a strange Country. So, our role as Whadjuk senior men in this part of the country is to facilitate the process for people to come and lay their people to rest in a cultural way.”

This coming week, from Monday November 4 to Friday November 8, Aboriginal community delegates from around the State will hold a series of private healing and commemoration ceremonies. Men will gather at Wadjemup and women at Manjaree (Bathers Beach, Fremantle), where their forbears once lit fires for homesick prisoners to see from the island.

Karen Jacobs at Manjaree/Bathers Beach, Fremantle. Credit Philip Gostelow

“It’s quite a phenomenal ceremony that we’re undertaking,” says Karen Jacobs, a Whadjuk elder who in 2006 was the first Aboriginal person to join the Rottnest Island Authority board. “We will have representatives from almost every language group in the state. We haven’t done that before for a very long time. We women will be here on the sands as the sun rises.”

Those private cultural protocols will prepare the ground for Wadjemup Wirin Bidi, a special public commemoration day at the island on Saturday November 9 (Wirin Bidi means Spirit Trail). This public event offers all community members an opportunity to share an occasion for awareness, reflection and reconciliation.

“They are going to come out and sing their songs and let them know that they’re thinking about them and miss them,” Garlett says. “It’s probably the first time that those people in the graves will have heard the languages of their own Country through the voices of their own people singing their songs in their language.”

Wadjemup faces unfinished business. For decades, its past as a prison island was erased as it was converted into a holiday playground and sunnily promoted as a tourist paradise of quokkas and idyllic beaches. While it is certainly that – it is also Australia’s biggest single deaths in custody site.

The Wadjemup Project is working to reconcile this conflicted history through truth-telling and educational activities, cultural ceremonies and the installation of permanent memorials at The Quod and the burial ground.

Jacobs says the ceremonies next week will acknowledge Wadjemup’s ongoing significance to the local Whadjuk Noongar people from before it was cut from the mainland 7000 years ago, and how its post-colonial use as a prison island ruptured and traumatised Aboriginal families all around WA.

In attendance will be people who have family links to the nearly 4000 Aboriginal men and boys taken from their communities and imprisoned on the island between 1838 and 1931. At least 373 are confirmed to lie in the burial ground.

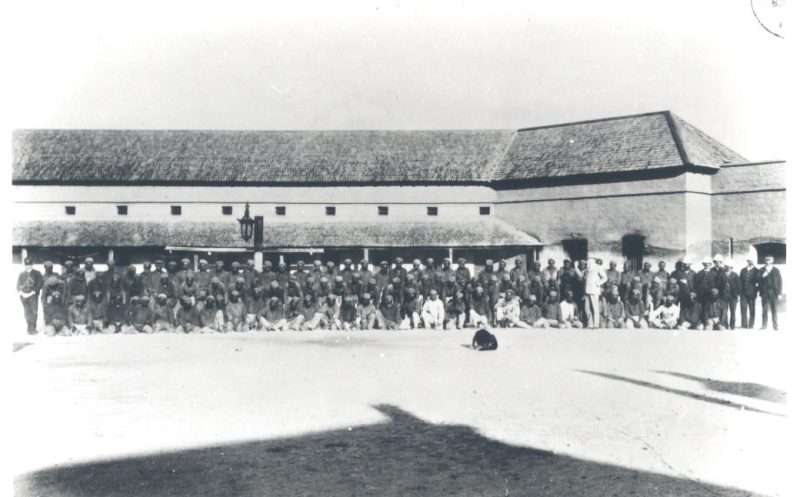

Aboriginal men and boys at the Quod in 1885. Image: Wadjemup Museum Collection

For decades, holidaymakers pitched their tents on the unmarked graves or stayed in hotel rooms converted from the Quod’s original prison cells. The “Tent Land” camping area was closed and relocated in 2007, but The Quod remained open as part of a resort until 2018. A new resort is being built nearby and is due to open in coming months.

The concealment of the past compounded the devastation in Aboriginal communities. But it also failed holidaymakers, who deserved to know the truth in order make more informed decisions about where they stayed overnight.

Many might have asked themselves how they’d feel about inviting paying guests to pitch their tents at an unmarked Karrakatta Cemetery without properly informing them, while disregarding the protests from families of the deceased.

Elder Neville Collard is a former WA police detective who now runs tours on the island. He received an early lesson in the levels of despair over Wadjemup from his grandfather after hitching a ride on a boat to the island as a 12-year-old boy.

“I didn’t know there was a prison here, or a mortuary,” Collard says. “When I went back home, my grandfather said, ‘Go and cut the green leaves’ and we did a smoking ceremony. When I asked why, he said, ‘To get rid of the evil spirits from the island’.

“And ever since then, I remembered that whenever I came here, when I returned home, I’d have to do a smoking ceremony to cleanse myself. When I came over here and worked in the police force in 1976-77, Tent Land was still in place and people weren’t behaving in a manner that they should around a cemetery.”

It is a brutal, unresolved contradiction that has demanded attention for decades since at least 1970, when the first remains were disturbed during sewer earthworks. Further disturbances in the 1980s and 90s amplified the anger and activism from the Aboriginal community.

After the decades of hard grind, bureaucratic impasses and the combined forces of activism and consultation, the Aboriginal-led Wadjemup Project was established by the State Government in 2020. It is being facilitated by the Rottnest Island Authority, with support from the Department of the Premier and Cabinet.

Garlett, Jacobs, Bropho and other Elders comprising the Wadjemup Whadjuk Cultural Authority, assisted by Richard Walley, have been consulting regional Aboriginal communities Statewide about how to redress those wrongs, including truth-telling measures to ensure visitors are better informed about the island’s complete history.

“People can come over and have a good holiday and have a good time, but at the end of the day it’s what’s under the ground,” says Whadjuk Cultural Authority member Herbert Bropho. “We need to teach you about the history. That’s all we want to do. We don’t want to spoil people’s holidays, and people taking photos of the quokkas,” he says.

“It’s not taking away your holiday. It’s not taking away your lifestyle. It’s not taking away your happiness. And when you come here it’s just, ‘Please sit and listen, and let us sit together and then move forward slowly with the truth’.”

Herbert Bropho walks towards the Quod at Settlement . Image: Philip Gostelow

Their consultations have led to a recommendation that The Quod be turned into a Museum of Remembrance and the Wadjemup Aboriginal Burial Gound be preserved as a permanent place of commemoration.

Ensuring the history of Aboriginal people on the island is recognised is imperative for reconciliation and will begin the healing process of historic and intergeneration trauma.

The process also offers non-Aboriginal people the opportunity to deepen their respectful connection to the island, its cultural significance and its compelling history.

One such opportunity for learning is offered at the Wadjemup Museum, where the new Wadjemup Wirin Bidi exhibition shares the stories of prisoners, the families who were left behind and the work being done through the Wadjemup Project.

Running through to June 2025, its displays include a historical prison cell door, shackles, artworks by Julie Dowling and Sharyn Egan, audio recordings and a film featuring four spiritual Noongar stories of Wadjemup.

“This is about healing, this is about reconciliation,” Bropho says. “This is about a lot of other things besides what happened here, you know. It’s for the future. We see a lot of soft tours going around, with people saying, ‘Oh, you know, it’s a great place to come and have a holiday.’ And it is. But it has a very dark past and people just need to that deeper understanding about what happened.

“And it’s not only for us. It’s for the rest of WA, you know, black, white, brindle, whatever it is, this is their path too as well, and they need to know the truth.”

The free public Wadjemup Wirin Bidi Commemoration Day is at Wadjemup on Saturday November 9 from 10 am – 2.15 pm. More details here.

The Wadjemup Wirin Bidi Exhibition is at the Wadjemup Museum until June 30.

* Stephen Bevis is a freelance writer, journalist and communications specialist. His previous roles include Arts Editor at The West Australian and Communications Manager at Perth Festival.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

* If you’d like to COMMENT on this or any of our stories, don’t hesitate to email our Editor.

** WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

*** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!

****AND Shipees, here’s how to ORDER YOUR FSN MERCH. Fabulous Tees with great options now available!