It’s 20 years on June 26 since the publication of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, the first in the seven-book series. The Philosopher’s Stone has sold more than 450 million copies and been translated into 79 languages; the series has inspired a movie franchise, a dedicated fan website, and spinoff stories.

I recall the long periods of frustration and excited anticipation as my son and I waited for each new instalment of the series. This experience of waiting is one we share with other fans who read it progressively across the ten years between the publication of the first and last Potter novel. It is not an experience contemporary readers can recreate.

The Harry Potter series has been celebrated for encouraging children to read, condemned as a commercial rather than a literary success and had its status as literature challenged. Rowling’s writing was described as “basic”, “awkward”, “clumsy” and “flat”. A Guardian article in 2007, just prior to the release of the final book in the series, was particularly scathing, calling her style “toxic”.

My own focus is on the pleasure of reading. I’m more interested in the enjoyment children experience reading Harry Potter, including the appeal of the stories. What was it about the story that engaged so many?

Before the books were a commercial success and highly marketed, children learnt about them from their peers. A community of Harry Potter readers and fans developed and grew as it became a commercial success. Like other fans, children gained cultural capital from the depth of their knowledge of the series.

My own son, on the autism spectrum, adored Harry Potter. He had me read each book in the series in order again (and again) while we waited for the next book to be released. And once we finished the new book, we would start the series again from the beginning. I knew those early books really well.

Assessing the series’ literary merit is not straightforward. In the context of concern about falling literacy rates, the Harry Potter series was initially widely celebrated for encouraging children – especially boys – to read. The books, particularly the early ones, won numerous awards and honours, including the Nestlé Smarties Book Prize three years in a row, and were shortlisted for the prestigious Carnegie Medal in 1998.

Criticism of the literary merit of the books, both scholarly and popular, appeared to coincide with the growing commercial and popular success of the series. Rowling was criticised for overuse of capital letters and exclamation marks, her use of speech or dialogue tags (which identify who is speaking) and her use of adverbs to provide specific information (for example, “said the boy miserably”).

The criticism was particularly prolific around the UK’s first conference on Harry Potter held at the prestigious University of St Andrews, Scotland in 2012. The focus of commentary seemed to be on the conference’s positioning of Harry Potter as a work of “literature” worthy of scholarly attention. As one article said of J.K. Rowling, she “may be a great storyteller, but she’s no Shakespeare”.

Even the most scathing of reviews of Rowling’s writing generally compliment her storytelling ability. This is often used to account for the popularity of the series, particularly with children. However, this has then been presented as further proof of Rowling’s failings as an author. It is as though the capacity to tell a compelling story can be completely divorced from the way a story is told.

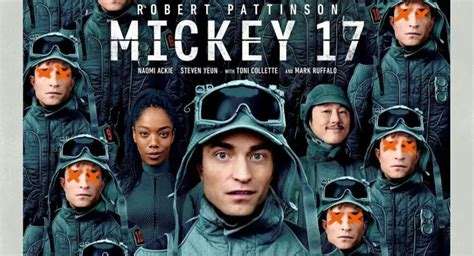

Daniel Radcliffe in his first outing as Harry Potter in the Philosopher’s Stone, 2001. Warner Brothers

Writing for kids

The assessment of the literary merits of a text is highly subjective. Children’s literature in particular may fare badly when assessed using adult measures of quality and according to adult tastes. Many children’s books, including picture books, pop-up books, flap books and multimedia texts are not amenable to conventional forms of literary analysis.

Books for younger children may seem simple and conventional when judged against adult standards. The use of speech tags in younger children’s books, for example, is frequently used to clarify who is talking for less experienced readers. The literary value of a children’s book is often closely tied to adults’ perception of a book’s educational value rather than the pleasure children may gain from reading or engaging with the book. For example, Rowling’s writing was criticised for not “stretching children” or teaching children “anything new about words”.

Many of the criticisms of Rowling’s writing are similar to those levelled at another popular children’s author, Enid Blyton. Like Rowling, Blyton’s writing has described by one commentator as “poison” for its “limited vocabulary”, “colourless” and “undemanding language”. Although children are overwhelmingly encouraged to read, it would appear that many adults view with suspicion books that are too popular with children.

There have been many defences of the literary merits of Harry Potter which extend beyond mere analysis of Rowling’s prose. The sheer volume of scholarly work that has been produced on the series and continues to be produced, even ten years after publication of the final book, attests to the richness and depth of the series.

A focus on children’s reading pleasure rather than on literary merit shifts the focus of research to a different set of questions. I will not pretend to know why Harry Potter appealed so strongly to my son but I suspect its familiarity, predictability and repetition were factors. These qualities are unlikely to score high by adult standards of literary merit but are a feature of children’s series fiction.

Di Dickenson, Director of Academic Program BA, School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()