One of the dubious benefits of getting older is to leisurely ponder the narratives and experiences of one’s past.

I say ‘dubious’ in deference to those who are hellbent in soaking up the joys and challenges of the present moment – as well as to those who prefer devoting chunks of their daily life to making plans. Good luck to both, but it’s not where I’m at.

Over the years, I’ve become adroit in sidestepping the demands of the present, while blocking out much of the future. Neophyte psychologists might label this a form of infantile regression, but I would prefer to think more sophisticated practitioners would recognise my looking-over-the-shoulder reverence as a hallmark of relaxed maturity. At least that’s what I tell myself.

Among my friends there are those who share my inclination towards retrospective musings. Often, this takes us back to our school days. We recall the quirks of teachers and fellow students; we regurgitate our sporting triumphs (or lack of them); we resurrect the concerts we attended; and we lament the girls we never asked out. Only occasionally do we talk about the academic side of things – the subjects we studied and how, if at all, they helped us comprehend the adult world we were soon to enter.

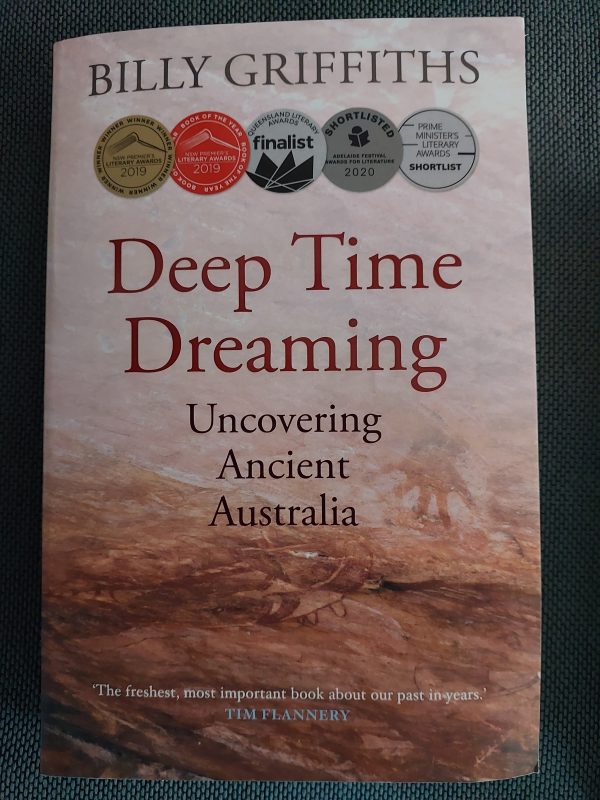

I was reminded of this while reading Billy Griffiths’ wonderful book Deep Time Dreaming, a meander through Australian archaeological history. Griffiths weaves a beautiful tapestry, revealing how past assumptions were overturned as a more complete picture of indigenous occupation emerged. He talks about the shifts in perception, brought about by technological advances due to radiocarbon dating, and by gradual recognition among white fellas that Australian ‘history’ had not begun when Dutch sailors landed on our western shoreline.

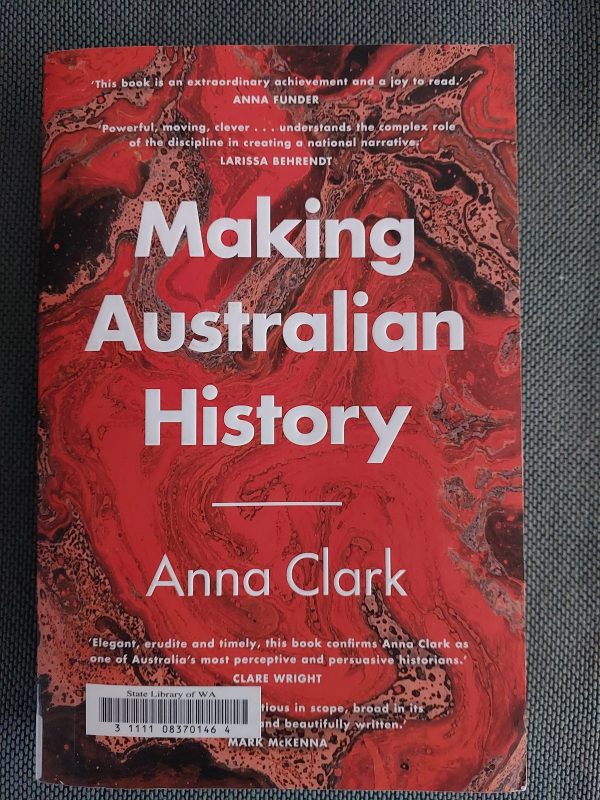

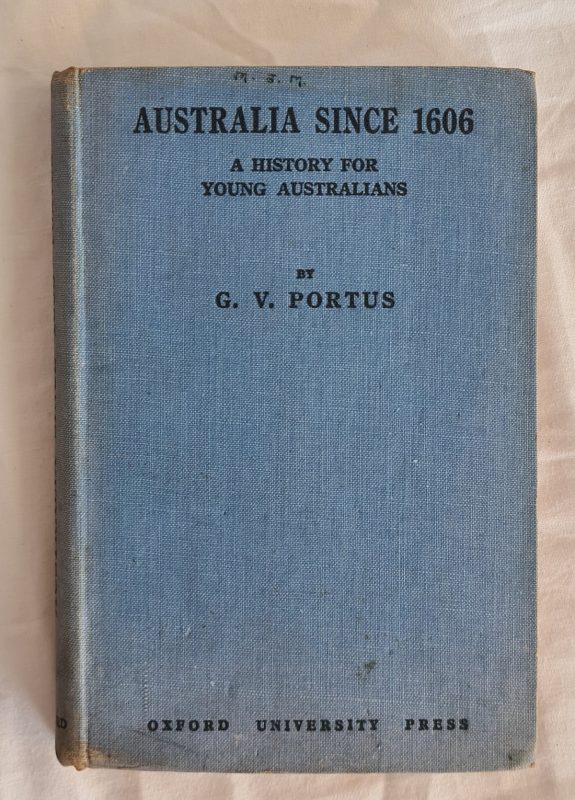

From the local library I borrowed Anna Clark‘s Making Australian History. Readers may know she’s Manning Clark’s granddaughter and an accomplished historian in her own right. Immediately, in the Index, I looked up GV Portus whose Australia Since 1606 was a prescribed text in my high school days. In a chapter headed ‘Silence’, Clark quotes Portus as describing the time before European contact as ‘a dark night’. This standpoint reflected other historians of that era, leading Clark to examine the ‘disciplinary silence’ that inhibited these historians from addressing what really happened to indigenous communities (let alone contemplating how life appeared through the lens of an indigenous person). It took the anthropologist, WEH Stanner, to burst the boil. In delivering the 1968 Boyer Lectures, Stanner took academia and entrenched wisdom to task. His argument carried weight and, as Clark notes, the discipline of History was ‘redefined’ in terms of ‘what it left out’.

Not that this penetrated my consciousness. In 1968, while Paris was burning and Chicago in full riot mode, I was a young graduate in Canberra, learning bureaucratic ropes. With one or two exceptions, none of my friends or colleagues showed much understanding of, or interest in, indigenous affairs. We had been enculturated at home, at school, and even at university. While we could argue and debate, our worldviews remained locked in a binary mode. Right or wrong; true or false; Left or Right. Post-modern thought had yet to make a mark and there was not much space for nuance, let alone encouragement to explore, unpack, or empathise with ‘otherness’. That, as one of my teaching friends remarks, came decades later.

More than fifty years on, I’m still learning, and shucking the dried molluscs of my own bias and ignorance. Good conversation, fine literature and historical treatises assist and invigorate.

It’s been said we arrive in the world as a tabla rasa – a blank slate, yet to be written upon. Genetics and, more recently, epigenetics, pulls the rug from under that notion. We do come with a clear imprint at birth yet are immediately exposed to elements that ripen and inform us. By the time we undergo formal schooling, euphemistically referred to as ‘education’, we have been conditioned by parents, peer groups, family members, religious figures, media personalities, and the norms of our society. Then come our schoolteachers. When we reach high school and perhaps have understood we can think for ourselves, it’s the luck of the draw whether we’re already straight-jacketed in comfortable conformity, or whether we’ve encountered adults who privilege curiosity over certainty. That’s why a great teacher stands out like a pink lotus in a pond. And it’s prompted me to canvass my contemporaries about how we were taught History, which textbooks were used, and whether our teachers turned us on, turned us off, or left us indifferent as to whether the past was worthy of study at all.

Feedback has been multilayered, much like my dear departed grandmother’s sponge cakes. Names and memories of teachers are splattered throughout the mix, although correspondents tend to differ on who taught what and when. Surprisingly, there is little criticism of those who taught History. Most school masters and mistresses are remembered with affection; some were clearly inspiring. When I attended the now-demolished Hollywood High School, Murray Mason, widely known as an art critic for the West Australian newspaper, turbocharged my interest. An old mate who attended Scotch College describes his teacher, a Mr Gear, as ‘passionate and enthusiastic’. At Perth Modern School, another friend had Tom Staples who was ‘taciturn’ yet a great teacher, especially around Australian History. A Canberra cobber who attended Mod also had Staples, portraying him as ‘a dry classicist’. At Methodist Ladies College, my sister, and her great buddy, found Mrs Hosford ‘brilliant’, a teacher who inculcated a real love of learning.

The content we were offered is another matter. I’m talking about 1960s Australia, where the study of History at secondary school level focused on the land of our birth, bookended by the United Kingdom – the cluster of countries where most of our forefathers originated, plus a splurge of 18th and 19th Century Europe, and a touch of the British Commonwealth – Canada, India, South Africa and perhaps a mention of New Zealand. Possibly, but not necessarily, the USA crossed our bows. I don’t remember the texts at Hollywood High, but one former student mentions Dennis Richard’s Modern Europe and Frank Crowley’s A Short History of Western Australia. At Perth Modern School – the elite State high school – Modern Britain, Modern Europe, and AGL Shaw’s A Short History of Australia formed the backbone of the History course at senior level. In the Private School domain, Scotch College used textbooks that included England in the Seventeenth Century (Ashley), and England in the Eighteenth Century (Plumb). Methodist Ladies College relied on Portus for Australian History. At St Hilda’s, another ‘ladies college’, there were no History texts, according to one informant who may or may not be reliable. Christ Church Grammar, where I rounded off my secondary schooling, also embraced Portus.

A cursory glance at the above reading list makes it clear where our history lessons were concentrated: Great Britain, its former colony – Australia, and Europe. You did not have to collect postage stamps to figure out the world was a somewhat larger paddock.

As for indigenous inhabitants, the landscape was bleak. Their presence was ignored, downplayed, or written off. To all intents and purposes, school students were inculcated in believing that Australian history began with the arrival of the first Europeans. Manning Clark, a radical and modern historian in comparison with many of his contemporaries, acknowledged late in his life he had not given due attention to what had been dismissively labelled ‘prehistory’.

As they say, shift happens. The advent of post-modernism encouraged a more nuanced approach, where multiple perspectives are tabled and considered. Teachers, students and (critically) academics were offered fresh eyes with which to view events of the past. Concurrently, Aboriginal activism and belated legislative recognition thrust the embedded ignorance and attitudes of whites into the spotlight. The tapestry of history was re-embroidered, giving shape and voice to a culture that hitherto had been diminished. And school curricula today reflect those changes, although some argue the pendulum has swung too far or that the subject has been dumbed down or neglected.

It’s a long time since I sat in a classroom. Like one or two of my more jaundiced correspondents, I remember an excruciating emphasis upon rote learning, though, unlike them, I didn’t recoil to any extent. Happily, I was not put off History, although I can understand others who were. Yet, with the passing of time, some friends write they have turned full circle. They now love History, not only for expanding their knowledge bases but also gaining appreciation and understanding of what has gone before. Some mention the resurgence of fascination with family history. A self-described former maths and science geek, recalls ‘too many dates and too many crusty white guys in wigs’, yet has come to relish anecdotes about his own family, ‘stories about real people in particular circumstances’. Pouring over old documents or travelling to locations where our migrating ancestors settled and struggled can engender intense feelings. New information, adding flesh to the bones of family stories. A sense of place; traces of lingering loss and sadness. Deep respect for the courage of folk who left their homelands, the young men who fought wars that were thrust upon them, and for the strong women who often held families together.

‘History’ will always be subject to debate and interpretation. Our opinions continue to reflect our biases and beliefs. But, as has been frequently propagated, we ignore the past at our peril. With so many strands of knowledge available at our digital fingertips, it’s a helluva ride trying to sort the wheat from the chaff. Yet, I reckon those of us who have absorbed a spirit of enquiry, coupled with a few decades of life experience, have a role to play in our collective evolution. One day soon, I’ll corner my grandkids and beat the drums of curiosity. ‘Come here,’ I might begin, ‘park your bums, and listen to this old bloke tell you some stories about the olden days’.

Any better ideas?

* Based in Fremantle, most of the time, Bruce Menzies is the author of three novels, a family history, and a recent memoir. Details at BruceJamesMenzies.com If you’d like to read more of Bruce Menzies’ work on Fremantle Shipping News or listen to a fascinating podcast interview with Bruce, look here

WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!