As part of my 25-year career as a Customs Officer, I spent a total of 13 years on Customs patrol vessels, just over half as a Launch Commander. During that time many noteworthy incidents happened, but the following account would be the most embarrassing. I have told very few people about it over the past 40 odd years, now the whole world will know about it.

Between 1976 and 1979, I was one of six crew members on ACV (Australian Customs Vessel) Jacana based in Broome, WA. On one of our patrols south of Broome we had a scheduled stop at Onslow overnight. The vessel was secured to the wharf in Beadon Creak, at the end of Beadon Creek Road. We intended having dinner at the Beadon Bay Hotel that night.

When leaving a vessel unattended the rise and fall of the tide is very important and needs to be factored in. The tides on this night were around 2m, which is a reasonable amount but not too drastic. Luckily, during the time we were to be absent from the Jacana, the tide was coming up to high tide then heading back down again so the mooring lines would require no adjustment, at least not until we returned that evening, meaning we could all go ‘up town’ for a meal.

Prior to our arrival we had notified the local police of our intended stay in their port. Sometime, just before 1800hrs, while we were getting ready to leave the vessel and proceed into town, one of the local police cars pulled up at the wharf and a friendly Police Officer offered us all a lift to the Hotel. We eagerly accepted his offer, but had second thoughts when we realised we had to travel in the back of the ‘Paddy Wagon’ (the only time I have ever been in the back of a ‘Paddy Wagon’ – luckily!). So off we went, in our ‘free’ taxi. We had (quite) a few beers and a typical pub type dinner, most enjoyable.

It was a typical Pilbara coastal location and the balmy night weather made it ideal for a walk back to the wharf, a distance of probably 1 to 1.5 km. We arrived back around 2230hrs with everyone turning in, except me, as it was my turn to do ‘anchor watch’ (even though we were moored to the wharf it was still called ‘anchor watch’) until 0200hrs in the morning.

There are several reasons for maintaining an ‘anchor watch’ all night, including checking that the anchor wasn’t dragging (if actually at anchor), monitoring the ropes (if alongside a wharf or jetty), maintaining a listening watch over all the radios (especially the emergency channels), ensuring the security of the vessel and monitoring the on-board generator to make sure it was behaving as it was responsible for keeping the fridge and freezer operating and running the air conditioners in the hot climate.

The HF radio monitoring the emergency channel 2182 was especially annoying at night because of the night-time atmospheric conditions creating a ‘bleed’ of nearby frequencies. All you could hear (all night) was a cacophony of Indonesian fishing boats talking to each other in Indonesian. Needless to say, this channel was turned down low and you hoped if anything important happened you would notice the difference.

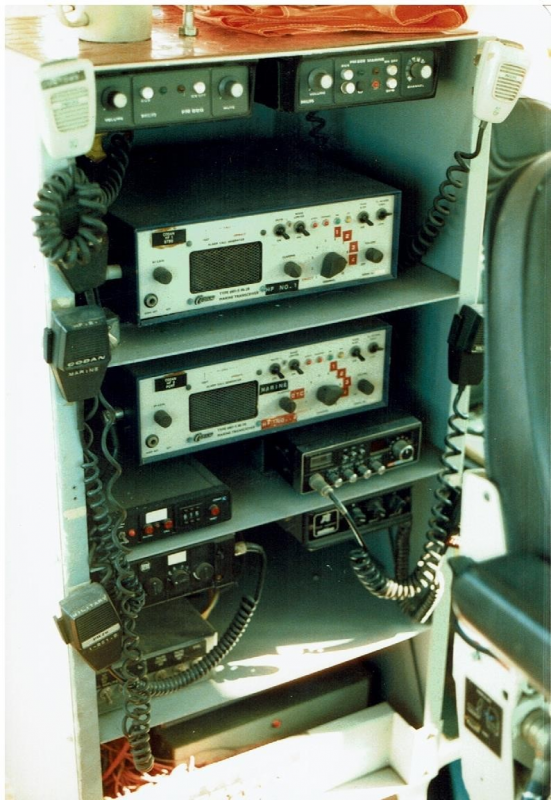

The other emergency channel was channel 16 VHF Marine Radio – very rare to hear much on this channel except during the day, but it still had to be monitored, as that is the whole point of having an emergency channel! Then there were several dedicated Customs frequencies. As this was before mobile or satellite phones, the only way to be contacted or make contact with one of the Customs base stations was on one of these frequencies (which one, depended on time of day and your location).

The layout of the wheelhouse where all the radios are situated and where most of the watch is spent is fairly important to this story. Starting at the front of the wheelhouse is the instrument panel with the helm chair immediately behind and in the centre. To the right of the helm chair is the radar operator’s chair. To the left of the helm chair (Port side) is a flight of stairs leading down to the forward accommodation area. Immediately behind the helm chair are two more seats side by side. These seats were spring/dampened ‘Bostrom’ truck seats complete with armrests. To the left and right of theses seats and slightly further aft were the Port & Starboard wheelhouse doors leading to the outside deck. Due to the previously mentioned balmy tropical nights, both theses doors were secured in the open position most of the time. At the rear of the wheelhouse, facing aft, was the chart table. Adjacent to this was a rack of all the radios, usually around half a dozen, encompassing the Marine radios, Customs radios, of HF, VHF, and UHF frequencies. Later there was the addition of a military radio, usually switched off unless instructed by Army, Navy or Airforce to switch it on and monitor a particular frequency.

If the middle armrests of the two Bostrom seats were swung up out of the way, you could lay across them with your head resting on one outside armrest (this night it was the portside one) and your legs bent at the knees, dangling over the other outside armrest. It was reasonably comfortable, and you were right in the middle of where you should be when it came to monitoring all the radios.

The only way I could successfully stay awake on anchor watch (especially in the early morning hours) was to read a book. My choice of book this night was one of Wilbur Smith’s many great titles (can’t remember which one). I remember it was classic Wilbur Smith, in as much as it grabbed your attention and wouldn’t let it go for quite some time. So, making myself comfortable laying across the two centre ‘Bostrom’ chairs, I was soon lost in the moment, time flashing past without me realising. At one point a thought started to develop along the lines of, ‘I’d better check how it’s all going’, but it quickly faded away and was instantly replaced with, ‘She’ll be right’ as the book got even more interesting and drew me in even deeper.

You may remember from earlier that the tide is now ebbing. After what I thought was about half an hour, but probably more like a whole hour or more, I decided I had better get up have a walk around and check the mooring lines and other ‘stuff’ was all ok.

I struggled slightly to get up from what had been a horizontal position. It was no longer horizontal but nearer to 25 deg listing to Starboard. None of this was sinking in at the time and, before I knew it, I was stumbling downhill toward the open starboard wheelhouse door, just arresting my headlong plunge as I got to the door.

‘What the…?’ ‘Oh shit’, now things were starting to make sense, looking across to the port side (now uphill) I could see the port gunwale had got caught up on top of the wharf as the tide had slowly dropped. It had all happened so slowly and so silently while I was absorbed (and therefore not paying attention) in the Wilbur Smith tale, that I hadn’t noticed a thing.

‘Crikey, what do I do now?’ Clambering back through the wheelhouse at an upward angle to the port side I stepped up and across to the wharf. Looking back at the boat, it looked at an even worse angle than when I was onboard. Got to do something and quick but what? I can’t ask any of the crew for help, as I would never hear the end of it.

Quickly searching around the wharf, I managed to locate a long, sizeable length of timber laying nearby. I could lift it, but it was bloody heavy. I shoved it down between the side of the hull and the wharf as near to where the gunwale was snagged as I could. Heaving with all my strength, I just managed to get Jacana unstuck from the wharf. As the gunwale slipped free, dropping about three quarters of a metre, the boat quickly started to compensate rocking first to Port then to Starboard about five times in ever-diminishing swings, until it is finally still again. At the time this seemed like an eternity but was probably all over in about 30 seconds.

About then, the Launch Commander comes up the companionway from the forward accommodation, rubbing the sleep form his eyes, asking “What just happened?” Quick as a flash I calmly said “Oh, a prawn trawler just went out in a hurry creating a large wash behind it.”

I think I got away with it, but it was a great lesson and taught me to be far more observant on future ‘anchor watches’.

Years later when I was a Launch Commander, I would instil in my crew that ‘anchor watches’ were very, very important as the safety of the vessel and the entire crew are in the hands of whoever is on ‘anchor watch’.

Moral of this story – Don’t just assume, actually check it out!

‘Jerboa’ a sister vessel to Jacana in the Fremantle Fishing Boat Harbour

* By Bernie Webb

** In case you missed Bernie Webb’s earlier articles here they are –

– Foxy Lady II – The Hash Stash

– MV Kota Bali – The Heroin Haul

** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!