The other day we heard an exchange on ABC radio’s Law Report between the defence lawyer for Australian prisoner and Wikileaks founder Julian Assange and ABC ’s law reporter Damian Carrick. It was about journalism.

Assange is facing espionage charges brought by US authorities and is before the UK courts resisting extradition. The charges emanate from him receiving and publishing leaked troves of classified files, among them the Iraq and Afghanistan “wars logs”, and diplomatic cables. In the public arena he is considered by some to be a terrorist and by others a hero of press freedom.

Carrick: “There’s also the argument that the publication of this kind of data doesn’t actually amount to journalism; it’s just simply putting out there a whole bunch of information. It’s not curated journalism as we traditionally understand it.”

Assange’s lawyer Jennifer Robinson counters this with a spirited submission about how Wikileaks partnered with a hundred media organisations to publish news stories, some of them winning journalism awards including Australia’s 2011 Walkley Award going to Wikileaks for Most Outstanding Contribution to Journalism.

“So, to suggest this is not journalism – take it up with the Walkley Foundation,” she says.

Well, that’s one way of determining the question. Journalism is what journalists say it is.

But journalists have no exclusive right to the practice. Anyone can do it. No licence. No training required. Grab your smart phone and publish stuff.

Nowadays so many people are doing just that. We’ve never seen such a variety of journalistic forms, thanks primarily to technology that allows us to create and share, to be editors and publishers. No need for the industrial machinery of printing presses and newsagents, or broadcast studios and transmitters. Not to mention licences and tons of money.

Now we have new generations of bloggers, citizen reporters, content creators, data visualisers, podcasters, influencers and the like. So, are these journalists too? Well . . . it depends.

One way to tackle the question is to look at the content and methods of their work. J-schools in universities and other learned observers of professional practice use criteria that cut across platforms and media formats.

Among these, the first test is whether the material being published is real, or true. “Never invent” said the Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter John Hersey, who wrote the monumental Hiroshima, which revealed to post-war America the human toll of atomic warfare.

Another imperative is to verify and contextualise information – or curate, as Carrick terms it. This procedure has been the hallmark of the great newspapers and broadcasters whose brands convey reliability and trust, born of checking and accounting for the information they use. This is laudable, but is coming under strain from reduced staffing, the rise of fake news peddlers and the 24-hour news cycle. In the face of these challenges, some have resorted to the lesser guarantee: “We’re never wrong for long”!

Underpinning these editorial methods lie some defining values, or instincts, that guide journalism and its practitioners: To be independent, to enlighten, to check power, some even to advocate, to provoke, to entertain.

Guided by such a taxonomy, most observers could feasibly identify a genus called journalism. But it’s big and getting bigger. It embraces a range of species, such as news reporters, feature writers, photographers, producers, documentary makers, illustrators, cartoonists, investigative reporters, columnists and reviewers. These survive in their various environments of traditional news media, book publishing, cinema, special interest websites, independent blogs – the list of these gets longer each week.

Looking closer still, you find the breeds of subject and specialist journalists covering their own niche, from gardening to computer games, food to foreign affairs, police rounds to politics, shopping to shipping news.

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

Just as we can observe similarities in the way journalists on different platforms go about their daily work, so can we see that the modern journalism menagerie has its ancestors. The travel blogger can trace a lineage back past Paul Theroux and Robert Louis Stevenson to travellers of ancient Greece and China. True crime podcasters have a great-uncle in Truman Capote, author of the first “nonfiction novel”, In Cold Blood.

All those COVID-shutdown Instagrammers have a counterpart in 18th Century Italy.

The panoply of political commentary, from shock jocks to Insiders, from Breitbart to Huffington Post, and, dare I add, this sprightly Fremantle organ, all share DNA with the pamphleteers of Revolutionary France.

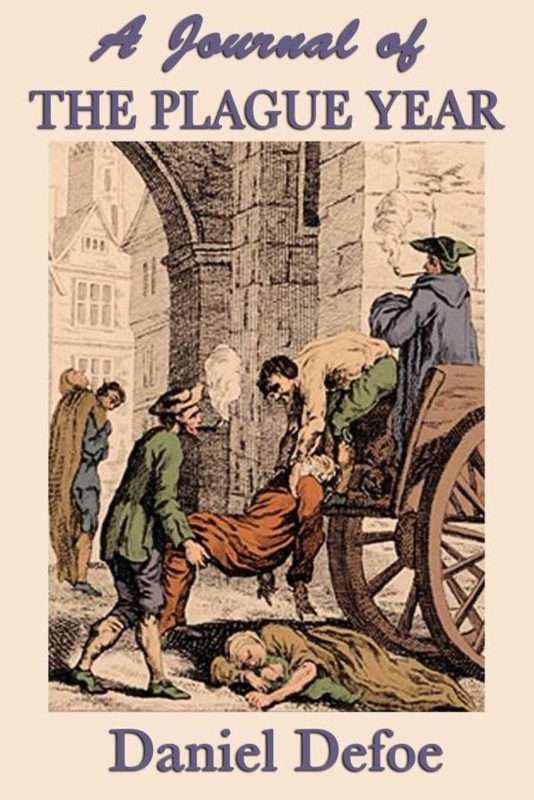

And the COVID curves of ABC TV’s data analyst Casey Briggs are the modern manisfestation of Daniel Defoe’s lists of parish burials in London’s Plague Year 1665.

Did I say Defoe? The mere mention takes us back to the start. Daniel Defoe is considered by some to be the first modern journalist and by others to be the greatest liar.

This shows just how long the debate about journalism has been raging. But then again those of us who believe in the vital role of journalism in a free society should expect, even welcome, this vigorous, continuing criticism of its practice. Let’s hope we take another few centuries before we settle on an answer.

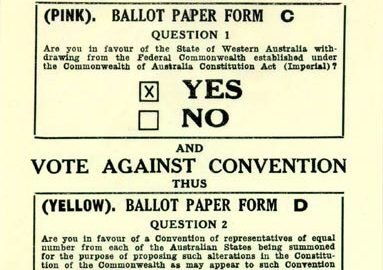

* This article was written by Chris Smyth, a former journalist, author and academic. He was chair of the national committee that handles ethics complaints against journalists. He declares he does not live in Fremantle, but occasionally visits to have a coffee and to get his electric bike fixed.