‘Our’ Tim Winton sets the scene nicely.

Credit: Fremantle Shipping News. Johnson Court dominates the cityscape – as seen from the Department of Communities, Kings Square/Walyalup Koort

In his 2013 fabulously Freo novel, Eyrie, Winton writes –

‘The building twitched in the wind, gave off its perpetual clank and moan of pipes, letting out the odd muffled scream. Ah, Mirador, what a homely pile she was.’

Soon after this, his protagonist Keely ‘sloped into the livingroom with its floor-to-ceiling window, and beheld the unstinting clarity of the western frontier: the shining sea, iron rooftops, flagpoles, Norfolk Island pines.

Winton then observes the Port and recites something of an ode to WA –

‘Port of Fremantle, gateway to the booming state of Western Australia. Which was, you could say, like Texas. Only it was big. Not to mention thin-skinned. And rich beyond dreaming. The greatest ore deposit in the world.’

And then, finally, he comes to our Freo –

‘…there she was at his feet. Good old Freo. Lying dazed and forsaken at the river mouth, the addled wharfside slapper whose good bones showed through despite the ravages of age and bad living. She was low-rise but high-rent, defiant and deluded in equal measure, her Georgian warehouses, Victorian pubs, limestone cottages and lacy verandahs spared only by a century of political neglect. Hunkered in the desert wind, cowering beneath the austral sun.’

Johnson Court at 23 Adelaide Street, Fremantle is the apartment block Tim Winton calls Mirador in Eyrie, set in the period following the GFC – the Global Financial Crisis – in 2008.

Winton accurately describes both the interior and exterior of the apartments at that time – indeed it’s said he wrote the novel in one of the apartments to get the feel right – but in the novel he has turned the building around so that it is fronting Adelaide Street rather than being side-on, hence giving better views over the city, the container port and the sea.

The building has a controversial history having replaced the Johnston Memorial Congregational Church which stood on the apartment building site between 1877 and 1968. The church was named after the long-serving and highly respected pastor, the Reverend Joseph Johnston, who died in 1892. In 1968, the church was demolished and replaced, a few years later, by a ten-storey retail/residential development – Johnson Court.

If you’d like to know more about the Reverend – who was born in England, went as a missionary to Tahiti and married there, returned to England, and then got the plum Freo job – you must read this most informative 1972 account of his life and times by Margaret Medcalf in the Australian Dictionary of Biography.

And if you wonder why the Fremantle Society soon bounded into being back in those heritage unconscious days of the 60s and early 70s, losing a building like this with a built history tracking back to the early days of the Colony of Western Australia, and Fremantle, explains why.

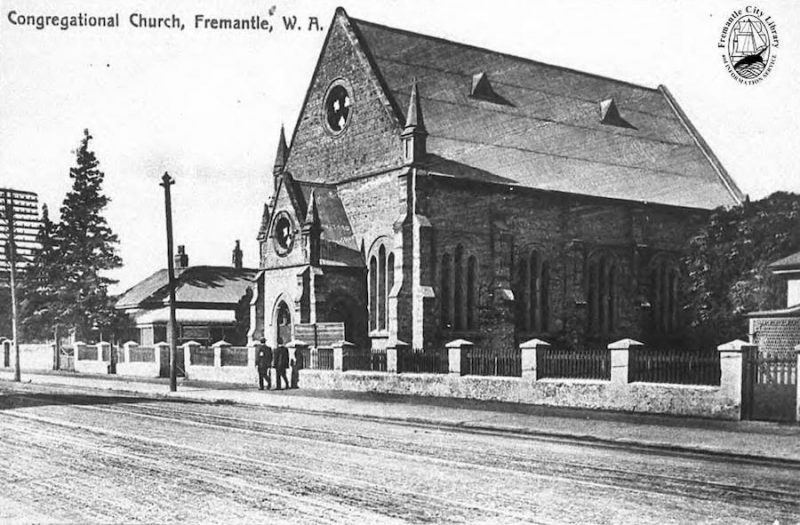

Here’s some old snaps of the Johnston Memorial Congregational Church, with thanks to Garry Gillard at Fremantle Stuff who has so lovingly collected them all together.

Credit Fremantle Stuff and City of Fremantle. Fremantle Library photograph #1227B and text: The foundation stone was laid by Henry Trigg on 24.12.1875. The church was designed by Mr Broomhall, the Clerk of Works for Fremantle, and J Manning. It was completed in July 1877 and demolished in December 1968. Photo taken after 1905.

Credit Fremantle Stuff and City of Fremantle. The Johnston Memorial Congregational Church was completed in July 1877 and demolished December 1968. Photo by Arthur Saxon. Fremantle Library photograph #1656 and text.

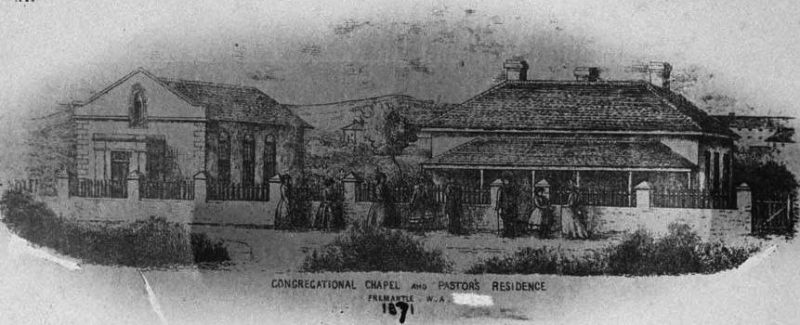

Credit Fremantle Stuff. A sketch reproduced on a postcard of the Congregational Chapel and the Pastor’s residence, dated 1871. The original Chapel was replaced by the Johnston Memorial Church: foundation stone laid in 1875, opened 1877 and demolished in December 1968. The Pastor’s residence is exactly as shown in 1885, but the Johnston Memorial Church was built to the right of the residence, ie the other side from the first Chapel. Rembrandt Studio, Fremantle Library photograph #5262 and text.

Soon after Johnson Court was built, the Mayor of the day and some councillors were reportedly aghast at its negative impact, and promised that something like it would never be built again.

Mind you, Arundel Court, as the apartment block at the corner of South Terrace and Arundel Street, Fremantle is now called, vies with Johnson Court as an example of the late 60s, early 70s inability of the community and its rulers to contemplate the fusion of the old with the new. Not surprisingly the Heritage Council has struggled to find any redeeming heritage qualities in Arundel Court.

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

Back to Johnson Court, it has been referred to as ‘the reviled Johnston Court’ in a Fremantle Society post from September 2016, and Garry Gillard in Fremantle Stuff explains ‘… [Johnston Memorial Congregational Church] was removed in favour of an appalling block of flats called Johnson Court – they couldn’t even get the name right’.

Good point. Wonder why they missed the ‘t’?

Johnson Court was one of the few high rise buildings in Fremantle until very recently and therefore drew critics’ attention as it was so out of line with the heritage buildings of the old town. However, currently under construction, opposite Johnson Court where the old Spotlight store and Westgate Mall once stood, is a new block of apartments and retail outlets which will be even taller than Johnson Court.

Johnson Court itself has undergone various up-grades in the past few years, including the installation of two lifts, and estate agents are now encouraging buyers and future residents with statements such as ‘Live in the Heart of Fremantle’, ‘Smart city living’, and ‘Live the Freo lifestyle’. All true, of course. How things change.

To emphasise this, of the 120 properties in the development approximately 60% are owner occupied, 40% rented.

While some of the flats are still available as social housing, many are now owned by investors who rent them out as short-term holiday stays.

The Mirador of Tim Winton’s novel has shaken off some of its menace.

From pariah to paragon of architectural and urban planning and design virtue, perhaps!

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

* This article was written by Jude Robison and Michael Barker