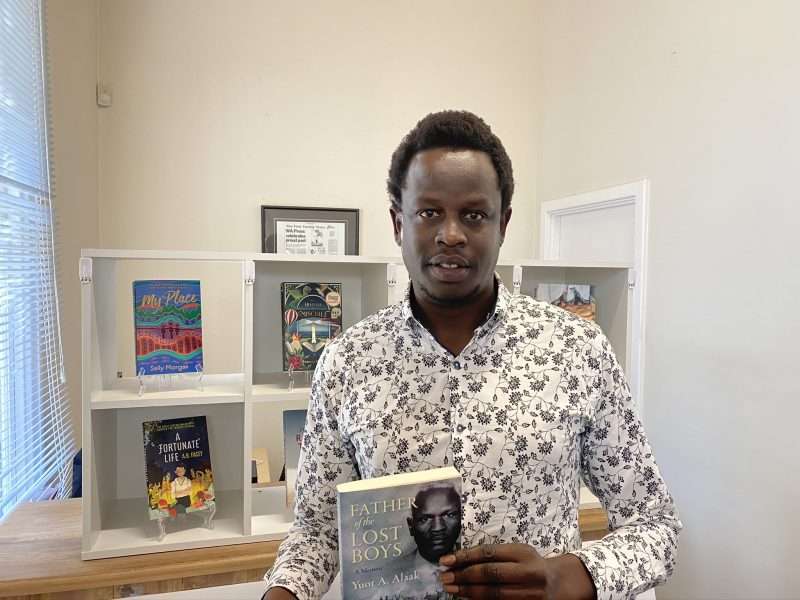

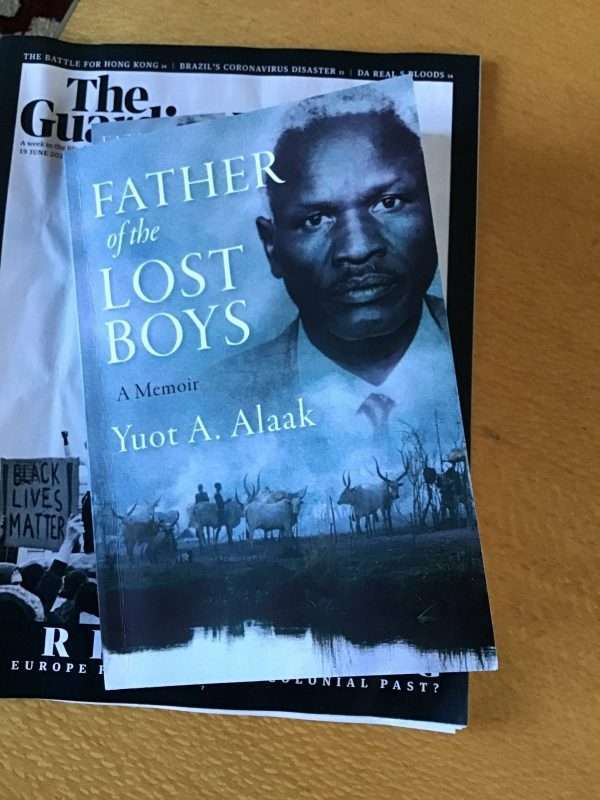

What an amazing story – it just had to be told!

And thanks to Fremantle Press, Yuot A Alaak’s account of his father’s heroics during the Second Sudanese Civil War is now available for us all to read – and marvel at.

It was then that Mecak (pronounced Meshak) Ajang Alaak stood in loco parentis to some 20,000 ‘Lost Boys’.

Mecak was a leading educator in South Sudan when the Second Civil War broke out in 1983. Yuot was then just a boy. His father was imprisoned – and believed to be dead – but eventually escaped his North Sudanese captors and took charge of some 16,000 boys from South Sudan who, to escape the clutches of the advancing North Sudan military forces, found their way across the border of Sudan and into Ethiopia, where they sought refuge. These were the Lost Boys.

Mecak always realised he had a choice in life. To advance the cause of his peoples with the gun or with the book. To be an armed freedom fighter for independence or to be an educator of his people. He chose to devote his life to the education of his fellow South Sudanese. His philosophy was, and remains, that, without education, his people will struggle to reach their potential as a democratic society.

So Mecak found himself in charge of the Lost Boys, including his son Yuot. When rebels in Ethiopia sympathetic to the North Sudanese Government then trained their guns on the Lost Boys, once again they had to flee their attackers. Mecak led them back into South Sudan, and eventually across another border, this time into Kenya, where again they took refuge. By his time, the cohort of Lost Boys had swelled to 20,000.

The story is harrowing. A long march across a raging river and marshy lands. Exposure to the elements – wild lions, leopards, crocodiles. Not to mention monstrous mosquitos; and limited food and medical supplies. And the air attacks by the North Sudan military never abated.

One hell of a movie, this story would make. But you are constantly reminded, this is not fiction, it’s fact.

Mecak Ajang Alaak and Yuot A Alaak

Before I read Lost Boys, my knowledge of the history of Sudan was anything but detailed. My English grandparents had given me a book titled ‘Gordon of Khartoum’ when I was a boy. It was in praise of British colonialism! For the Alaaks, Karthoum was enemy territory- the Arab, Muslim North. The North where the language spoken was not theirs, or that of any of the 64 tribes who make up the East African, Christian and Animist South. Khartoum in the North is thousands of kilometres from Bor in the South.

Yuot Alaak has included a very useful overview of the history of Sudan as an appendix to Lost Boys. Sudan is yet another outcome of colonialist politics in Africa. Over time they’ve all been there: Egypt and the Ottoman Empire; the Anglos and the Egyptians; the British alone; and then all the politics that followed the British withdrawal in 1956; then the First Civil War from 1955-1972 concluding with the Addis Ababa Agreement in 1972, when the South achieved a level of autonomy. The Second Civil War ended in 2005. That’s when a Comprehensive Peace Plan was signed. Then, on 9 July 2011, just on 9 years ago, South Sudan realised its status as a nation.

By that time, Mecak and Yuot were living in Australia. They left Nairobi, Kenya in 1995, with their family, as refugees, when Yuot was 16 years of age.

After independence, conflict unfortunately returned to the fledgling South Sudan nation. Disagreements among the 64 tribes of South Sudan were not easily resolved. However, as of February 2020, peace has reigned once again. Everyone hopes it holds.

In the final chapters of Lost Boys, Yuot reflects on these developments in his country of birth and the intensity of his feelings as an Australian and also a member of the South Sudanese diaspora. All people who have migrated to Australia – and there are so many – will feel his pain and his hope.

I was moved by this book’s story. It leaves you marvelling at the strength and resilience of the human spirit in the face of so many travails, hardships, losses and hostilities. You are reminded that there is virtually no place on the planet, and no time, where and when the human rights of peoples are not at risk, if not actively being violated.

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

You can buy from Fremantle Press or a good bookstore near you for $29.99.

As Editor of Fremantle Shipping News, I was recently extended the privilege of meeting and interviewing Mecak and Yuot Alaak, father and son. We discussed the events recounted in the book and so much more besides. Listen here. You won’t be disappointed.