During this, so far, quite short covid period – which has seen most of us in home confinement (dare one say prison?), save for the skilful execution of occasional mercy missions to the supermarket for supplies, and surreptitious late afternoon sorties to the beach for exercise – a casual glance at our neighbours/fellow inmates (not to mention ones partners and selves) suggests we have all begun dressing down big time.

Even on business-related Zoom video meetings from home people rarely seem to dress for the occasion. Are we beginning to witness another part of life that is changing forever – how we dress?

Perhaps as we start to contemplate what may be different when we resume our new normal, post-covid, lives we might begin to ponder whether we have in fact witnessed the end of fashion. (Now there’s a phrase, ‘end of fashion’. Good name for a local band, hey? Oh, it’s already been done? Ok!)

At least there might be a case for ending ‘fast fashion’ (although one should add that ‘End of Fast Fashion’ wouldn’t have been such a good band name, as ideologically sound as it might have been).

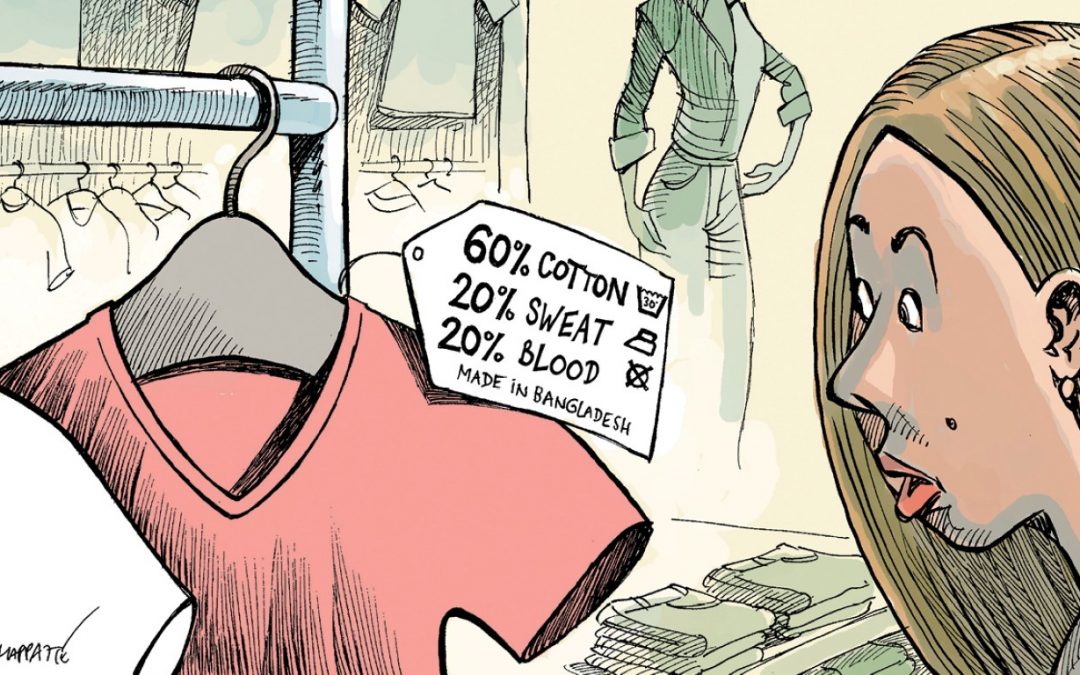

Fast fashion has been under attack for its bad, bad environmental credentials for some time, and a report just out basically implies it should be consigned to history now, if not yesterday, for all time. Basically it’s a relatively new phenomenon and not a good one. Driven by quick profits.

In a detailed Review published yesterday in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, academics Kirsi Niinimäki, Greg Peters, Helena Dahlbo, Patsy Perry, Timo Rissanen & Alison Gwilt emphasise that the fashion industry is the second largest industrial polluter after aviation, accounting for up to 10% of global pollution.

Despite the widely publicised environmental impacts, the authors note the industry continues to grow, in part due to the rise of fast fashion, which relies on cheap manufacturing, frequent consumption and short-lived garment use.

In their Review, they identify the environmental impacts at critical points in the textile and fashion value chain, from production to consumption, focusing on water use, chemical pollution, CO2 emissions and textile waste.

Impacts from the fashion industry are estimated to include over 92 million tonnes of waste produced per year and 1.5 trillion litres of water consumed.

On the basis of these environmental impacts, the Review argues for fundamental changes in the fashion business model, including a deceleration of manufacturing and the introduction of sustainable practices throughout the supply chain, as well a shift in consumer behaviour — namely, decreasing clothing purchases and increasing garment lifetimes.

The Review concludes that these sorts of changes stress the need for an urgent transition back to ‘slow’ fashion, minimizing and mitigating the detrimental environmental impacts, so as to improve the long-term sustainability of the fashion supply chain.

I wonder how many of us are ready to take up the challenge?

I am though beginning to hear of old fashion designers, or would-be old fashion designers, who have recovered their old Singers from the attic and begun cutting, pinning and sewing again! Maybe there’s hope. Especially here in the Fremantle area where ‘fashion’ is already a hard to define thing. As in most of Freo, nearly anything goes. Lucky for me.

I’m sure the secondhand roses, pre-loved (mainly women’s clothing stores instead what a fabulous range of inventive names they have, nearly as inventive as those of coffee shops) will be particularly pleased if we take on slow fashion.

I suspect it’s not so much the older demographic one needs to convince though, as the Zara demographic, and their mothers!

And it does seem it’s mainly a gender thing too, or have I got that wrong? Men are of course important admirers of fashion, as inert as they try to be when asked to contribute an informed opinion on the subject from time to time.

But maybe I’ve read the whole thing wrong, and the take of a near-septuagenarian male is, after all, not be considered, let alone relied on. (But plainly, I’m not giving up quickly, or easily; and I’m told 70 is the new 52.)

Mind you, when you consider the key points of the recent Review, I don’t think it’s all that difficult to put a persuasive case to end fast fashion sooner than later. Here they are –

- The textile and fashion industry has a long and complex supply chain, starting from agriculture and petrochemical production (for fibre production) to manufacturing, logistics and retail.

Each production step has an environmental impact due to water, material, chemical and energy use. - Many chemicals used in textile manufacturing are harmful for the environment, factory workers and consumers.

- Most environmental impacts occur in the textile-manufacturing and garment-manufacturing countries, but textile waste is found globally.

- Fast fashion has increased the material throughput in the system. Fashion brands are now producing almost twice the amount of clothing today compared with before the year 2000.

- Current fashion-consumption practices result in large amounts of textile waste, most of which is incinerated, landfilled or exported to developing countries.

Convinced? Wonderful. And think of all the money you can save!

If not fully convinced – and now you have all of Easter at home to devote to the study of this topic – read the whole, learned and footnoted Review and I’m sure you will be.

Happy Easter!