Fenians, Fremantle and Freedom Festival will take place from 5 – 14 January 2018. The Festival commemorates the Irish political prisoners who were transported on the Hougoumont – the last convict ship to Australia – which arrived in Fremantle on 10th January 1868.

This ten day festival will celebrate the part that Irish culture played in maintaining the resilience of these prisoners on their 89 day voyage.

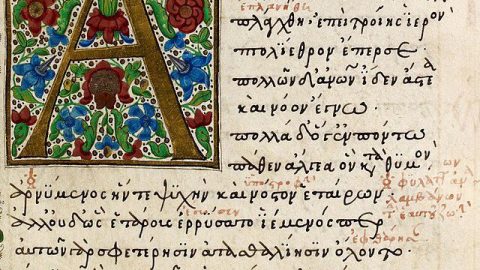

Drawing from their own writings, diaries, the newspaper The Wild Goose, which they wrote on board as well as the programs from concerts and sing-a-longs, we will bring to readers of the Shipping News a taster of the cultural treat you are in for this January.

The streets and buildings of Fremantle will be alive with the sounds of Irish music, theatre, contemporary Irish film, literature and dance. We’ll post more detail of the program as the dates get closer, but for now, join with us as we re-live the journey through the writings of the Fenians.

The Voyage

About the Hougoumont

The Hougoumont was built in 1852 for Duncan Dunbar, a highly successful ship owner, at his shipyard in Brema, Moulmein (Burma). Dunbar’s vessels were noted for their stoutness, being constructed of teak, cut from the forests that lined the river surrounding his shipyards.

Named after Chateau d’Hougoumont (occupied, fortified and held by the British at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815) the Hougoumont was a three-masted, full rigged Blackwall Frigate of 875 tons. The length was 167’ 5”; Breadth 34’; Depth 23’. (Blackwall Frigate is the generic name given to a series of over 120 three-masted, wooden-hulled sailing ships, first designed and constructed at Blackwall on the Thames.)

The voyage to Western Australia took 89 days and the Hougoumont arrived in Fremantle with 108 passengers and 280 convicts, including 62 Fenians (45 civilian and 17 military). There was one death during the voyage – a poor Irishman, not a Fenian.

Of the 108 passengers, most were pensioner guards and their families – 44 pensioner guards, 18 wives, 10 sons and 15 daughters. One passenger was a Catholic priest, Father Bernard Delaney who administered to the convicts. The remaining passengers have not been accounted for but were possibly cabin passengers or regular soldiers. William Cozens and W. Smith were the captain and surgeon respectively.

Preparing to depart

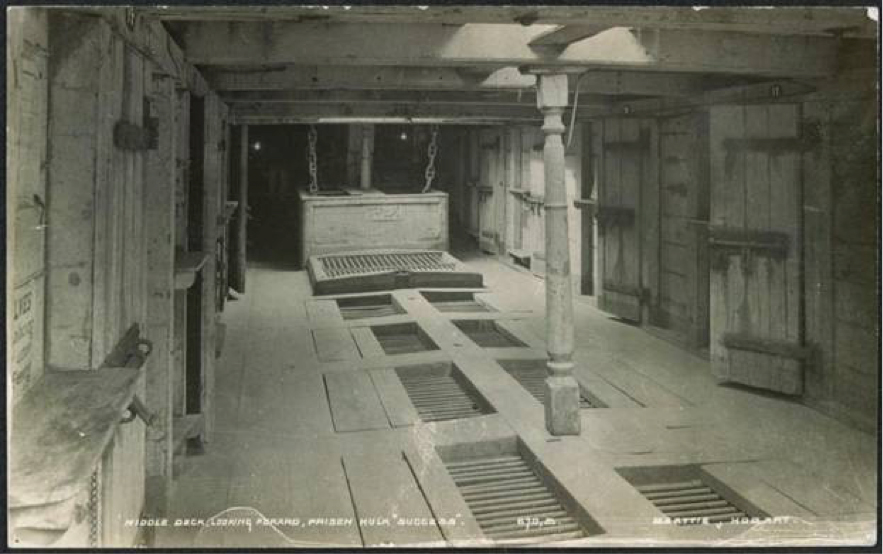

No vessel was specially designed and built for the purpose of transporting people, so before leaving England, the Hougoumont was fitted out as a convict ship. Her deck and hold were divided into compartments; those below being separated by heavy bulkheads while, on deck, there were wooden barriers with side doors where soldiers with fixed bayonets on their loaded rifles were posted.

The hatch coverings which opened to the lower deck, or hold, were generally removed to allow for air and light. An immense iron barred gritting surrounded each hatchway from deck to hold. Viewed from below, every hatchway stood in the centre of the ship, like a great iron cage, with a door through which the warders entered and a ladder to climb to the upper deck.

Like many other ships used for transportation, it was actually a British merchant ship chartered for the convict service.

“Only those who have stood within the bars, and heard the din of devils and the appalling sounds of despair, blended in a diapason that made every hatch mouth a vent of hell, can imagine the horrors of the hold of a convict ship.” John Boyle O’Reilly

Fenians joining the ship

From the Diary of Denis B Cashman… 30th September 1867:

I was roused at about 3.45 on this morning and desired to dress in the new clothes, that not a moment was to be lost. So I hurriedly got into them, and marched into the corridor, where I was joined by 21 others, and marched in single file to the reception ward, where we had an augment of six more. Here we were placed eight in a cell and whilst breakfast was being served I indulged in the first chat for nine months. I now heard for the first time that my dear friend John Flood was going, which considerably cheered me.

After a hurried breakfast and a hearty shake of the hand from every Gael who hove in sight, we were placed in rank along the ward to answer a Roll Call, after which we were chained together (two in a gang), our lads being all separated and mixed with the ordinary convicts. I had the misfortune to be chained to a foxy animal, who growled like a bear if I diverged a jot from my course to shake hands with a friend fore or aft.

We were marched out of the prison (Millbank) across the quay and on board the gun boat Earnest on route for the Hougoumont lying at Sheerness which ship was to convey us on our long journey, away from dear friends and country, to our exile in Western Australia.

Crossing the quay before embarkation, I cast a look behind, and can almost now feel the pleasurable sensation which filled me, when I found myself on the outside of the gloomy and grim looking pile, with its towers, iron windows and cold frowning aspect, where I had spent the most miserable seven months of my life.

When we got on board the Earnest steam was up, and after a few moments she got under way. Once on board, the silent system, to which, since my arrest on the 11th of January I had been so rigorously subject, was totally exploded. By Jove didn’t we talk, shake hands, and enjoy the pleasure of hearing ourselves to the best of our inclinations.

Passing down the Thames, I caught a glimpse of several of the buildings in that quarter of the city. I certainly had a splendid view through the small circular window of the cabin in which I was stowed, of the houses of Commons and Lords. I thought the Parliament House was the most beautiful and splendid piece of architecture I had ever beheld. It is a chef d’oeuvre of the most florid gothic style, and embellished from the base to the summit of its lofty towers with one mass of ornament, foliage and beauty. The portion of the Westminster Bridge which I saw was also very beautiful, in fact in keeping with the style of the exquisite pyle, from opposite which it crosses the Thames.

A little further on I saw Somerset House, now used for public offices. It is a splendid edifice, but from the restlessness of the animal to whom I was chained, and indeed the general rush of my friends to the small window, I was unable to see sufficient of it to impress my mind with its style. I saw several other pretty buildings, the names of which I can’t remember.

As creature comforts are not to be despised (even by convicts) at about 12.30 p.m. we applied to our haversacks, with which we were furnished, and dined off a lump of cold meat and bread to allay the cravings of the inner man.

At about 3.00 p.m., we arrived at Sheerness, and were immediately taken on board the Hougoumont where we, for some time, stood the scrutiny of the spectators who gathered ’round, I presume to see for themselves what species of animal the Fenians resembled.

When arrangements had been made, and again answering to our names, we were ordered below, where we were assigned bunks and our locations, and formed into messes of eight men each. All my messmates, with the exception of Kelly [John Edward] were strangers to me; nevertheless we very shortly fraternised and became good friends. One man from each mess was Captain, whose duty it was to draw provisions etc.

There were now 36 political prisoners on board, but we expect to take on more at Portland Prison, to which we were bound. A few hours after we came on board, a tug steamer brought us more prisoners, amongst whom I recognised seven or eight political prisoners (military) with whom I was in D Ward at Millbank. They left Millbank for the public works about three months previously. The poor fellows looked much altered and worn out since I saw them. This (30th September) was to me an eventful day, after long months of monotony and ennui which I had at Millbank, and I was heartily glad for a change of any sort, – Out of the lot I recognized a few friends – And I doubt if we slept much this our first night at Sea. Several of our men took fits – I escaped thank God. Denis B Cashman

1st October 1867:

This morning we were on deck at 6.00 am; the morning was beautiful. The ship sailing under full canvas. I enjoyed this morning very much, one day having so much changed (for the better0 my position, and I heartily returned the numerous greetings of my friends. I had a long chat with John flood, and again old memories and scenes were reviewed, thus agreeably passed the first day. We occasionally had a fine view of coastal scenery passing down the channel for the next few days. Denis B Cashman

2nd October 1867:

We put into Portsmouth to get a new spar to replace one which was broken on the previous night. We weighed anchor the same day and arrived at Spithead. Denis B Cashman

6th October 1879:

Dropped anchor in Portland Roads, Next day we took a good many prisoners on board, among came Con Mahony, Brophy, Jack (John Boyle) O’Reilly and a lot more. A Clergyman, the Rev M Delany came on board – I was glad to hear that he was going to accompany us on our voyage.

Denis B Cashman