“Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred. Human-caused climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe. This has led to widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people.” (The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, 2023. IPCC is the leading international body for assessment of climate change.)

The short period between the end of the recent referendum process and commencement of the 28th United Nations climate change conference, known as the COP (Conference of the Parties), at the beginning of December is a good time to reconsider the way we think in terms of our responsibilities to each other and to the planet.

Many thousands of words have been written examining the failure of the Voice referendum in which the majority of Australians refused to ratify Indigenous people as the First Nations people with the right to formally advise the Federal government on matters of concern such as disproportionately high levels of imprisonment, poor health and education outcomes and high mortality rates. Blame for the referendum’s failure has been variously attributed to the negative influence of powerful political interests, and a few indigenous leaders who, for different reasons, also advocated No.

What is still unfolding is the question of ‘where to now’ which, in a general sense, must include a doubling down on the representation of Indigenous peoples and culture in formal decision-making, as well as continuing to understand and value the 65,000-plus years of history which is the inheritance of all Australians and integral to developing a deep and rich sense of place. Consulting, meaningfully and effectively with Indigenous people ‘to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures’ is mandated under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People.

Effectively, the ‘no’ vote supported the status quo, the familiar state of affairs which has, historically, favoured non-Indigenous people. It was a vote for no change, regardless of the impact of that decision on Indigenous people and on Australia as a whole. In a very deep sense, wanting to preserve the status quo has serious implications for a number of issues affecting the world, most especially climate change.

It is a common analogy but, in terms of climate change, many of us are like the frog sitting in water slowly coming to the boil without registering that the water has become fatally hot. The one major, urgent and often overlooked thing that each of us must change, therefore, is the way we think, in order to respond urgently and act differently.

At present the dominant voices of concern about climate change are the persistent and informed voices of scientists, various concerned organisations, and the sometimes isolated and radical actions of young activists, who are increasingly being targeted by police. What is missing, and reducing the effectiveness of these groups, is a large popular movement such as supported the anti-nuclear movement in the 1980s. At that time, people were concerned about the possibility of nuclear war and of nuclear accidents. Now, future generations face the certain end of life on the planet if change does not occur, so why aren’t more people screaming at our politicians to address the main problem of climate change: the fossil fuel companies?

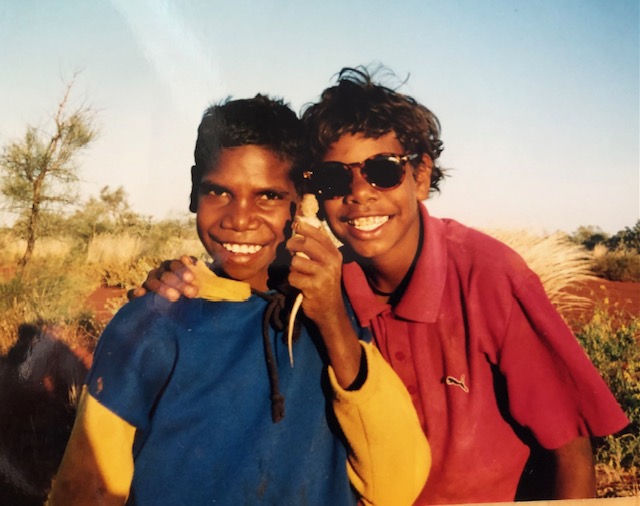

Credit JenniferSumpton Photography

Our thinking, as 21st century humans, must change because Western cultures, in particular, are based in individualism; the idea that we are free and autonomous individuals with discrete rights which impacts on everything around us, including climate change, war and racism. The title of this article suggests another way. An essential first step to improving our lives is to think of our responsibilities as well as our rights, with each of us becoming custodians for the future by acting now, connecting with others, and respecting our interconnectedness and our connection to the natural world.

Each of us needs to decide what kind of individual we will be. Will we all change our priorities and urgently address our footprint on the planet, or will we continue to live in comfort and do whatever suits us – in our workplaces, families and businesses – without consideration of the consequences?

Gregory Bateson, famed anthropologist, suggested that the inextricable nature of the relationships we have with each other and with the natural world is necessarily delicate and complex, and that paying attention requires great sensitivity. To keep that sensitivity to the forefront of our decision-making, he said, requires a humility that acknowledges deeply that we cannot know everything. On this basis, inevitably, we need to support and engage with each other to make an impact at a global level. Unquestionably, there is a complexity and depth to all peoples and such differences must be attended to and addressed. In their decision-making Indigenous Australians are noted for their long meetings in which all are heard. But being present and paying attention is also necessary if change is to be supported.

In the 1990s, with my brother Jonathon, I visited an Aboriginal community near Alice Springs, where Jon had been teaching. A group of boys gathered around him excited about the basketballs he had brought from Alice. One of the boys grabbed my hand, another asked to wear my sunnies and we all walked together into the bush. One young boy, aged about nine, and I stood looking at some nearby soft, waving, light-filled spinifex seemingly floating over the deep red earth. See? he said. I shook my head. He darted forward, put his hand part-way into a hole and grabbed the tail of a pale, fat lizard, holding it aloft to the delight of his friends. He beamed at me. Success! I had been looking at the aesthetics of ‘the landscape’ while he had been on the lookout for movement, probably for supper. Lacking his astute attention—perhaps to some tumbling grains of sand outside the hole – I was blind to the possibilities right in front of me.

At this point in time, when the survival of the planet is at stake and our communication is global, all our lives are interlinked. It is prime time for all of us to take into account, in all we do, how we think of our actions and decisions in relation to others, locally and globally. It is not a radical idea that we live in a deeply interconnected relationship with others and with our environment, but how seriously do our decision-makers take that reality? And how sensitive are our political and corporate leaders to our interconnectedness?

Society’s decision-makers (from politicians and corporate leaders to company board members) all, directly and indirectly, affect our lives. We can think of them as actors in the dual sense of playing a part and acting to make things happen. In their roles, they might have to minimise the negative effects of their decisions on others to ensure a short-term gain or profit is made, whether that ‘profit’ comes in the form of dollars, acquisition of land and property, or simply the maintenance of power. The work of the actors or decision-makers can also be compromised because their time-frames are necessarily short and often aimed at achieving short-term benefits. These men and women must fail to care for our future though many might share our pain, hope and longing for a better world.

Because each decision-maker is empowered by virtue of their various positions and offices, their final decisions can appear to be inviolable, set in stone and beyond the challenge of ordinary people. Such decision-makers cannot be custodians for the future, or custodians for our children’s future, or for our biological and ecological future, without pressure being brought to bear on them by all of us.

What activists (who are also, ordinary people) tend to recognise more than the average law-abiding citizen is that decision-making individuals are all naked emperors. And if we saw them as they are – as vulnerable and imperfect rather than as invulnerable czars – then more of us might pressure them to make the right decisions for all the interconnected, affected communities in Australia and around the world. The so-called travesty that was enacted when young activists attempted to protest outside CEO of Woodside, Meg O’Neill’s house was never going to be an actual invasion of privacy, but it was an act which brought to public awareness that one of the key fossil fuel companies of Australia and the world is led by an ordinary person – someone’s neighbour living in a suburb like you – someone making decisions to continue to pollute at higher and higher levels with the tacit support of the State government, in turn enabled by a mostly compliant population.

How does this relate to the referendum? Non-Indigenous people have a sense they are born into rights. However, Indigenous people comment they are born into responsibility. The word ‘custodian’ is often used by Indigenous people to describe their responsibilities for the land, for culture, for each other and for future generations. The phrase ‘custodians for the future’ suggests we all direct our energies to putting pressure on decision-makers to ensure the planet is a fit place to live for generations to come.

Recently, at Murdoch University, a philosophy seminar debated the topic of whether the time had come to end non-violent protest and turn to violence to address climate change issues and protect our planet from carbon emissions. It was a hypothetical question aimed at producing debate but, as a proposed topic, it was confronting. Non-violence, after all, is an ethic that, in principle, once adopted, should not have a use-by date. But it did make me think (frog in warm water that I am, as you are): are things really that bad? Since then, several people have pointed out to me, in conversation, that many of the young people they know are choosing not to have children, and many refer to this era as an apocalypse, the end of days for humanity. I needed more information.

After listening to an old interview with former US vice-president Al Gore, the driving force behind the 2006 climate change film An Inconvenient Truth and its 2017 sequel, An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power, I checked online where he was at on the issues he had raised earlier. His 2023 Ted Talk “What the Fossil Fuel companies don’t want you to know” shows him railing against these companies whom he sees as just like the tobacco companies, using lies, deceit and influence to protect their profits. He points out that, if we were able to walk vertically, in an hour we would reach the outside of the band of oxygen that surrounds our planet with all the greenhouses gases below us. Fossil fuels, as the central problem of climate change (and the problematic tactics of these companies), was discussed at the recent Politics in the Pub event with invited climate change experts.

Gore points out that fossil fuel companies exercise an insidious power within the United Nations climate change conference, known as the COP (Conference of the Parties). Later this year, the president of COP 28 in Dubai will be the CEO of the United Arab Emirate’s national oil company, Adnoc. According to The Guardian newspaper:

“Sultan Al Jaber is overseeing expansion to produce oil and gas equivalent to 7.5bn barrels of oil, according to new data, 90% of which would have to remain in the ground to meet the net zero scenario set out by the International Energy Agency. Adnoc is the world’s 11th biggest oil and gas producer and delivered more than a billion barrels of oil equivalent (BBOE) in 2021. However, the company has big short-term expansion plans, the new analysis shows, with plans to add 7.6 BBOE to its production portfolio in the coming years – the fifth largest increase in the world.”

We are all being pushed forward by a history informed by self-interest and it is this that each of one of us must change. To refuse to see how relationship and interconnection inform everything we do is to reduce others to contextless entities, to reduce people and problems to signs rather than to cultural complexities of time and place. It is an undeniable fact that the world has benefitted from listening to previously marginalised voices and that many of those marginalised voices have been eventually recognised. Gore cites Nelson Mandela saying that ‘nothing changes until it does’. That’s how it works.

Change comes; it is slow, sometimes glacial, but change does come. The difference now is that change cannot be glacial; the world is in too much physical distress.

So, what can you do? It is not easy to take action on your own, at least not initially, so think about getting together with others and, as custodians for the future, become better informed, talk, write, read and act. Watch the video of the recent Fremantle Network’s ‘Politics in the Pub’ where climate change scientist Bill Hare suggests we are on track to exceed the 1.5-degree target limitation agreed at COP in 2015 (the Paris agreement), the level necessary to protect the most vulnerable, low-lying nations (do note though, this target can still be attained with the continuing rise in renewables).

Custodians for our future must include anybody of an age able to act, take on and understand responsibility. Action is an antidote to despair and in many countries around the world the young become adults when they become responsible. Above all, be willing to step up to have an influence on decision-makers, recognising that they are ordinary people like you, who must take advice widely, particularly from those affected by their decisions. Actually, that is all of us.

* By Dr Christine Owen

** This is an extended version of an article which first appeared in the social policy journal ‘Pearls and Irritations’.

WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!