On the morning of 16 July 1945, a plutonium implosion device was detonated atop a 100-foot tower in a remote part of the New Mexico desert. The resulting blast turned night into day and heralded the start of the Atomic Age. Tomorrow marks the 80th anniversary of the test. Photographer Brett Leigh Dicks recently visited ground zero to explore what has atomic tourists flocking to the site 80 years later.

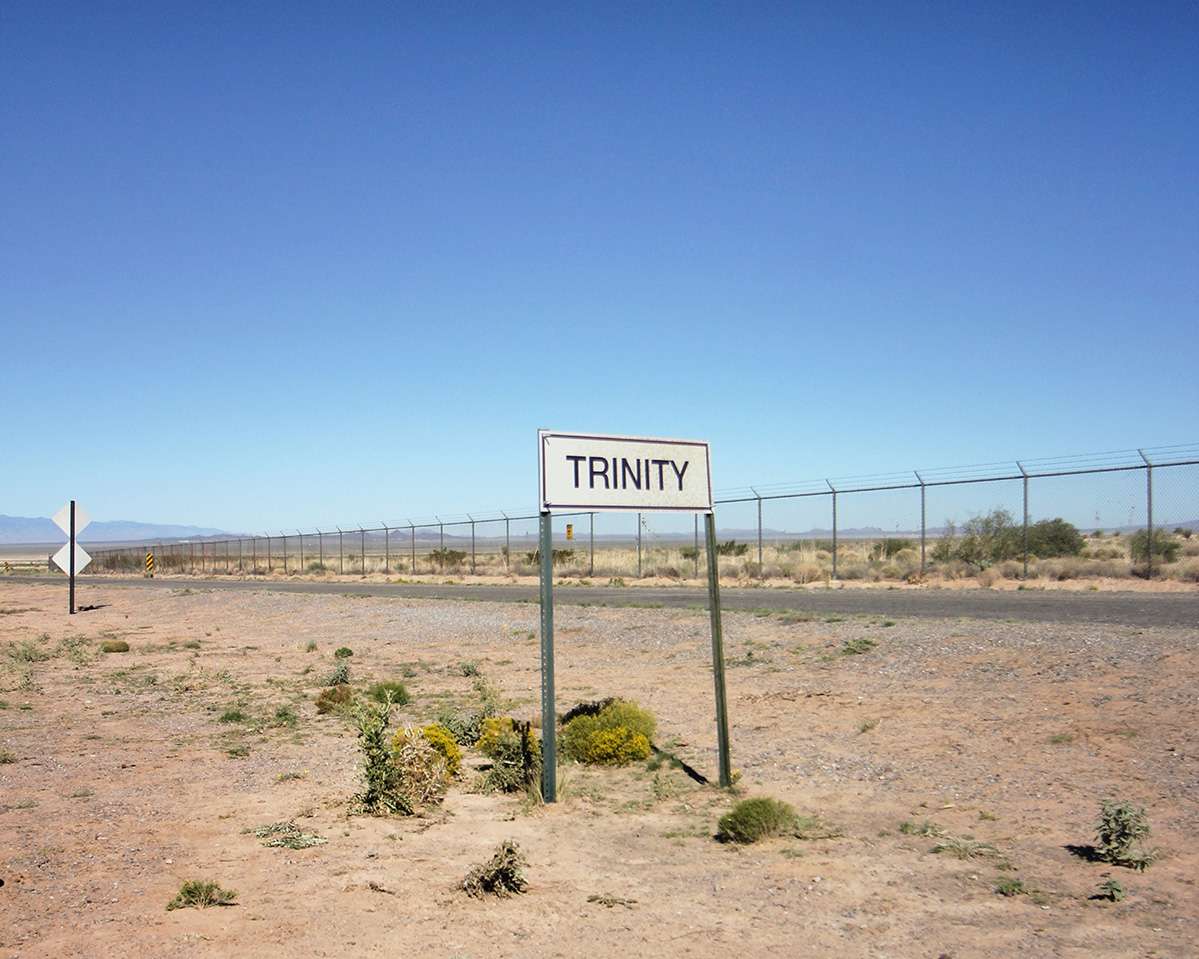

As you arrive at the Trinity Test Site, the surrounding desert sparkles in the morning sun. But there’s much more to the twinkling than meets the eye. The glittering in this stretch of New Mexico’s Jornada del Muerto desert is the result of tiny green fragments of glass-like rock strewn across the desert floor, an artefact of the menacing event that took place here 80 years prior. At precisely 5:29am on the morning of 16 July 1945, the United States Army conducted the world’s first detonation of a nuclear device in this remote part of southern New Mexico.

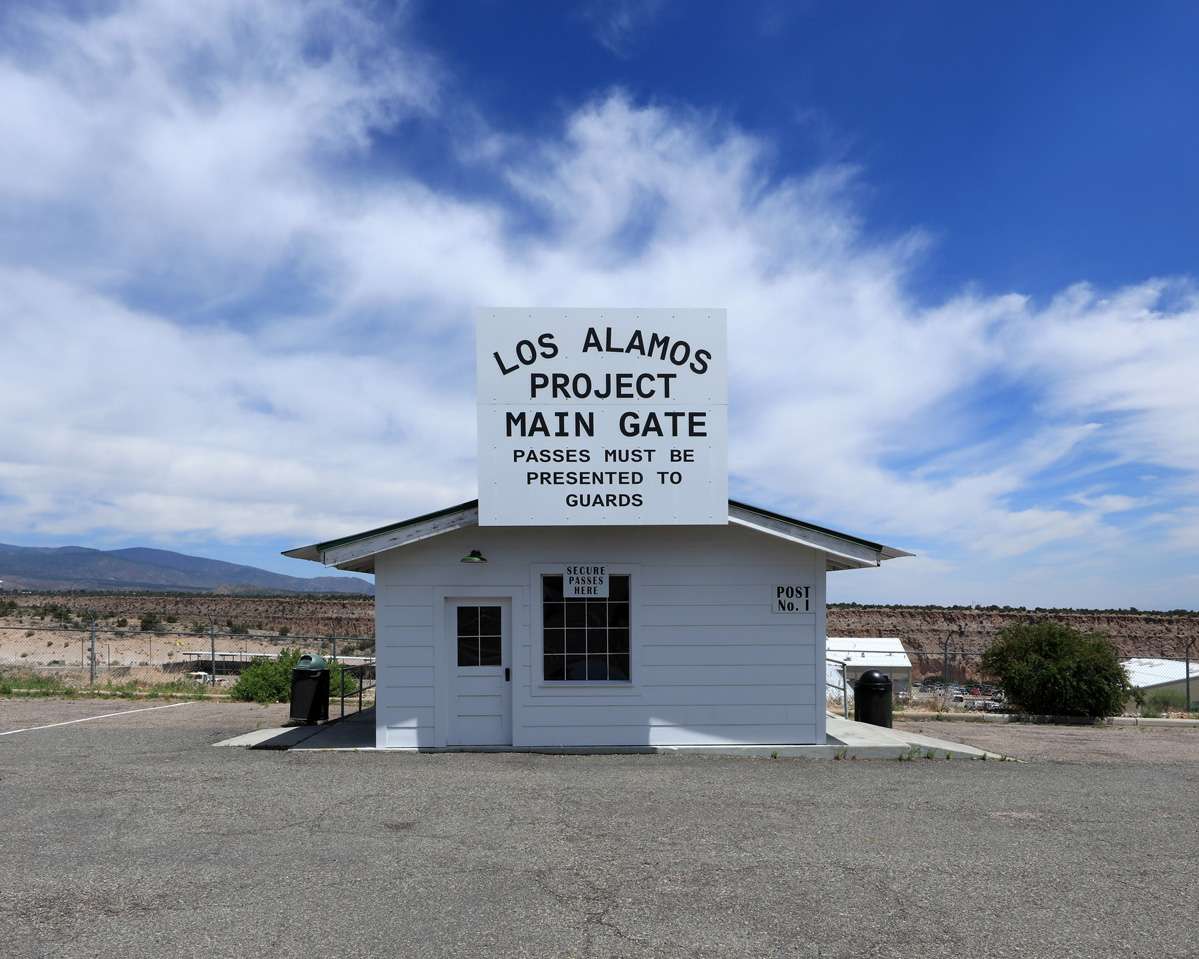

Codenamed Trinity, the test was a defining moment within the secretive Manhattan Project, a World War II US Army research and development program charged with creating a nuclear weapon. Under the direction of Major General Leslie Richard Groves Jr, in October 1942 J Robert Oppenheimer was appointed to establish and direct a secret weapons laboratory. Oppenheimer chose the seclusion of Los Alamos, New Mexico as the location to design and construct the weapon with a site near Alamogordo, around 250 miles south of the laboratory, selected to test the device.

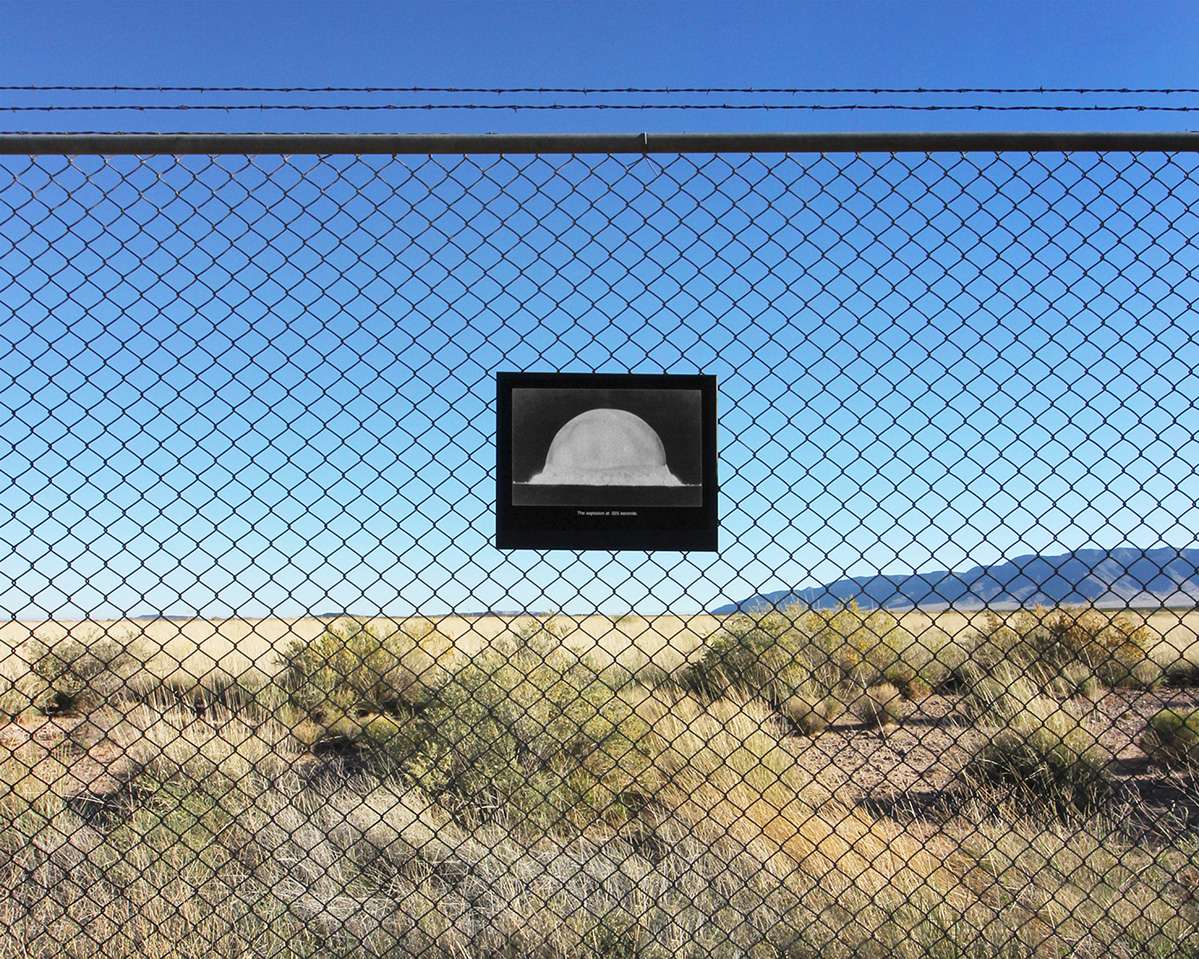

Upon detonation, the blast produced a yield of 25 kilotons of TNT and was felt over 100 miles away. A forest ranger 150 miles west of the blast saw the fiery flash while a member of the public 150 miles to the north said the explosion “lighted up the sky like the sun.” The blast sent a mushroom cloud billowing 7.5 miles into the sky while the associate fireball melted the surrounding desert. It also thrust the world into the nuclear age and changed the world’s socio-political climate across the decades to come.

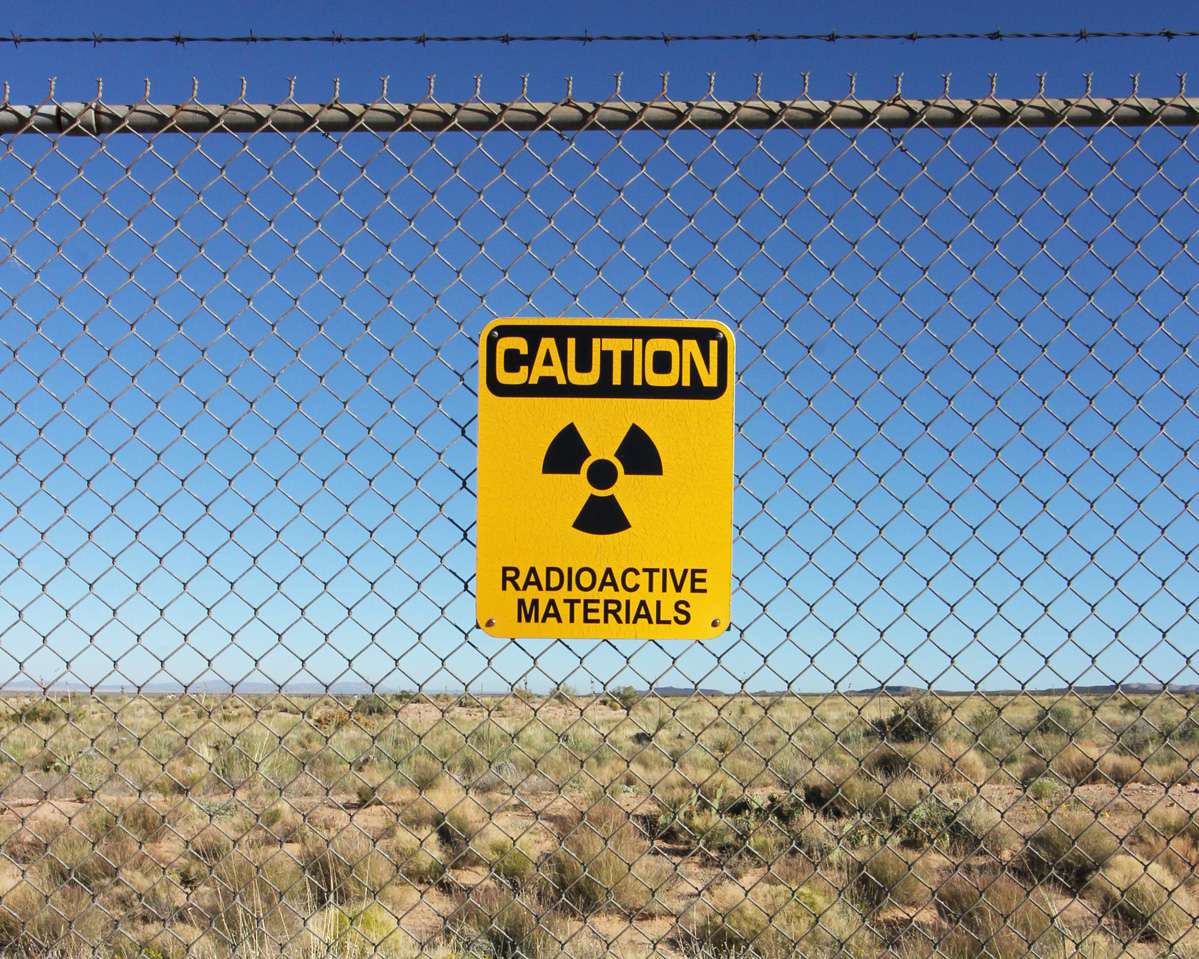

Situated on the White Sands Missile Range, in 1965 the test site was declared a National Historic Landmark. Twice a year the United Sites Army, which oversees operations at the missile range, opens the gates at Trinity Test Site to the public. While the scene in Christopher Nolan’s recent Oscar-winning biopic, “Oppenheimer” that depicted the Trinity blast offers a chilling visual and sonic experience, walking the baren landscape where the test took place provides an even more poignant experience of the events that changed the course of world history.

Located approximately 35 miles southeast of Socorro, on the first Saturday of April and third Saturday of October, atomic tourists flock to the desert to explore both the blast site and the nearby support facility where the plutonium core of the bomb was assembled. Access to the Trinity Test Site is via the facility’s Stallion Gate on New Mexico State Highway 525. The gate opens to the public at 8:00 a.m. and the public is permitted to enter the range until 2:00 p.m. Since the site is an active military installation everyone 18 years and over must have government-issued photo identification while foreign nationals will also need their passport and a valid visa. Proof of insurance and registration for your vehicle or a rental agreement is also required to enter the base.

Given the Open Day’s popularity, it’s best to make an early start. The nearest accommodation is located in Socorro, approximately 25 miles from the Stallion Gate, but motels fill up months in advance. Accommodation can also be found a little further afield, in Truth or Consequences (75 miles south), Albuquerque (95 miles north), and Alamogordo (110 miles east). With only one entrance open to the public, cars start lining up at the range’s main gate as early as 3:00 a.m. and by 6:00 a.m. the queue typically stretches for miles along Highway 525.

Having checked out of my hotel room in Socorro around 4:15 a.m., I reached the Stallion Gate at approximately 5:00 a.m. The line of cars waiting to enter the site was already over a mile long. After claiming a place in the queue, I walked toward the lowered boom gate at the front of the line. A family from El Paso were preparing a tailgate breakfast in the bed of their pickup while a little further along, a retired couple from Arizona were reclining in collapsible chairs next to their car. There were retirees, ex-servicemen, college students, and family members of scientists and soldiers who participated in the test.

From the Stallion Gate, it’s 17 miles to the test site. While photography is permitted at both Ground Zero and the McDonald Ranch House – where the plutonium core of the bomb was assembled – elsewhere on the base it’s strictly prohibited, including along the drive from the gate to the test site. Upon arriving at the test site, volunteers are on hand to direct parking. Once parked, it’s a short walk to Ground Zero.

Ground Zero is denoted by a 12-foot lava-rock obelisk that was constructed in 1965 by army personnel using local rocks collected from the surrounding range. During the Open Day the surrounding chain link fence hosts an outdoor display of historic photographs while other displays include a post-World War II atomic bomb casing and the rusting remnants of Jumbo, a 214-ton steel and concrete container designed to hold the precious core of the device in case of a nuclear misfire.

Shuttle buses are on hand to transport visitors the two miles from Ground Zero to the McDonald Ranch House. As scientists assembled the bomb’s plutonium core, jeeps were apparently positioned outside the ranch house with their engines running in case a quick getaway was needed. Once assembled, the core was carefully transported to Ground Zero and inserted into the bomb assembly before the device was raised to the top of the tower. The resulting blast not only created a crater that measured 4.7 feet deep and 88 yards wide, its intensity melted the surrounding desert in a radius of approximately 300 yards, turning its silica into a distinctive green radioactive glass called Trinitite.

The Trinity test was the precursor to the atomic bombings of both Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. After the bombings, Oppenheimer reportedly sent a letter to the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, to express concerns shared by a growing number of scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project about the military and political consequences of nuclear weapons. He subsequently resigned as director of the Los Alamos Laboratory at the end of the war, but by then his nuclear-fuelled genie was well and truly out of the bottle.

NOTE: An exhibition of Brett’s atomic-related photography, titled NUCLEAR LANDSCAPES, takes place at Fremantle’s Moores Building Art Space 13 – 28 September, 2025. For more information, visit Nuclear Landscapes.

Brett Leigh Dicks is an American/Australian photographer and writer based in Fremantle. He has written and photographed for The New York Times, VICE, The Sunday Times and Rhythms Magazine. For 20 years he was based in California and wrote about music for the Santa Barbara Independent and Santa Barbara News-Press. For more articles and photographs by Brett on Fremantle Shipping News, look here.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

* If you’d like to COMMENT on this or any of our stories, don’t hesitate to email our Editor.

** WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

*** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!