In March this year, the Urban Bushland Council Inc hosted an excellent day of talks on the flora and geology of our remnant coastal limestone ridges at the City of Cockburn Wildlife Centre. Why? might you say. It’s just scrub! Not so! There exists a finely balanced and rare flora association, surviving despite these areas being used variously for grazing (until the 1950s), a dumping ground for unwanted bits and pieces (including cars), mining of limestone, road building and unsanctioned clearing for informal recreation activities. Effective from 15 November 2023, the Australian Government through the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water recognised the Threatened Ecological Community or TEC of the Honeymyrtle shrubland of the limestone ridges of the Swan Coastal Plain Bioregion and its significance as critically endangered.

Shrubland on Manning Park Ridge

The Tamala Limestone along the western edge of the Swan Coastal Plain formed over some 800,000 or more years during an extended period of glacial/interglacial cycles with landward advancing dune systems forming during the colder and more arid periods. Sea levels in their last iteration rose from around 150 metres below current levels at 120,000 years ago, when the coastline was many kilometres further west, to stabilise at today’s level around 6,000-5,000 years ago. Along the coastline extending from Shark Bay in the north to near Albany in the south the prominent ridges and hills of karst limestone formed – deposits of quartz and calcite sands which consolidated via chemical reactions and compaction. These prominent limestone landscapes then weathered, forming striking structures such as the well known Pinnacles and cave systems such as those at Yanchep and between Yallingup and Augusta. As described by Emeritus Professor Ken McNamara, this unique and globally recognised karst limestone system then shaped the flora and fauna that inhabited it.

Tamala limestone in North Fremantle

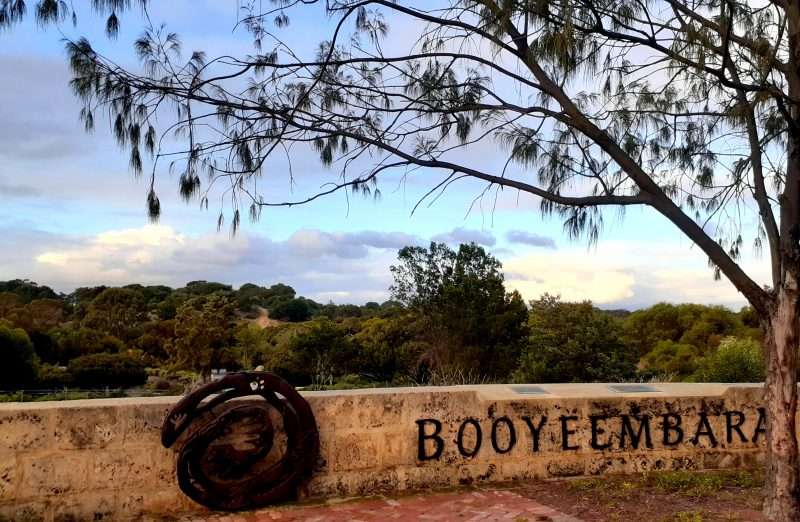

Prior to the occupation of Western Australia by the British in the early 1800’s, the ridges in the Fremantle area were prominent landmarks. Early artworks show a far more undulating terrain with substantial hills. Noongar knowledge holder, Iva Haywood-Jackson, described how the limestone hills, a creation of the Waugal, were of significance to the Whadjuk Noongar inhabitants as part of the stories of the Seven Sisters as well as barriers keeping the fresh lakes and ocean waters apart. However, the limestone was also highly prized for construction and was mined to build many of the new British colonists’ homes, commercial and industrial buildings as well as other civic structures. The landscape and its flora and fauna changed considerably and rapidly. Along our coast there are remnants of that former landscape, some more intact than others, including Buckland Hill and environs, Cypress Hill, Cantonment Hill, Booyeembara Park/Royal Fremantle Golf Course, Monument Hill, Clontarf Hill and Manning Park Ridge.

Our coastal soils are notoriously poor in nutrients. From an agriculture perspective they are particularly low in nitrates and phosphorus rendering their use as limited and challenging. Despite this, they host a unique and large range of endemic species of plants which in turn support a large range of fauna. The plant association is striking and rare. The plant assemblage of the Honeymyrtle shrubland typically includes Banksia sessilis (parrot bush), Melaleuca systena (coastal honeymyrtle) and Melaleuca hueglii (chenille honeymyrtle) and only occurs on shallow skeletal soils on the slopes and tops of highly restricted locations on the limestone ridges extending from near Guilderton in the north to near Lake Clifton in the south. Other plants that may be present in parts of the broader limestone ridge communities include other species of banksias, melaleucas, wattles, sedges, grevilleas, gums and more. The shrubland is particularly important in that it provides a variety of food for many nectar, seed and fruit eating birds and browsing mammals, and a significant food source for endangered Carnaby’s and Baudin’s cockatoos. Of particular significance is, with clearing and reduction of feeding areas for the black cockatoos, nearly all seed of some species is consumed leaving little to contribute to the seedbank retained in the soils. After fires, such seed banks are critical for the regeneration of the shrublands in particular.

Carnaby’s Black Cockatoo. Credit Jennifer Sumpton

In addition to being a food source for birds, the scrubland variously provides ideal habitat for an extensive range of fauna, including reptiles (skinks, the western bearded dragon, blind snakes, legless lizards, birds (including insectivorous and other predatory birds) and mammals including kangaroos, quendas, possums and native rats, as well as the ubiquitous introduced species such as foxes, cats and rabbits.

King skink

A key focus of one talk, presented by Emeritus Professor Hans Lambers, was on the highly significant flora of the Manning Park Ridge and its adjacent lake. While the soils are notoriously poor in nitrogen and phosphorous, many of the species at this park are well adapted to the low phosphorous soils. Banksia sessilis in particular has adapted with growth of shallow cluster root systems that are able to mobilise any available phosphorous – though this root system makes the species far more vulnerable to much drier conditions – such as we are seeing currently with browning over large areas of the ridge.

Other speakers discussed critical research being carried out on the food sources for the black cockatoos and the Carnabys in particular. Seeds of banksias, pine nuts, pecans and macadamias have been tested for their nutritional value availability and weight. However, the results for Banksia sessilis were surprising. While the seed is small, clumping of the bushes on these limestone sites provide a substantial source of food. Protection of these TEC environments, and the Honeymyrtle shrubland in particular, play a highly significant role in supporting bird and other wildlife in the coastal environment.

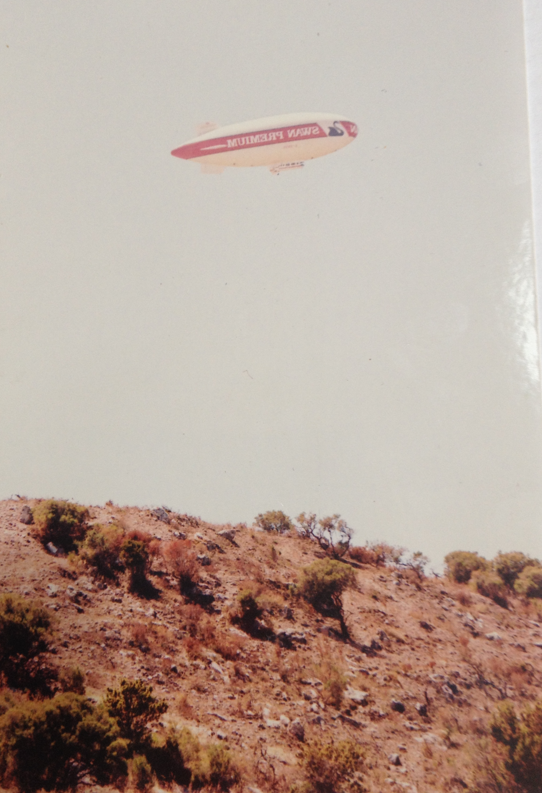

East side of Manning Park Ridge 1983 (courtesy Robyn Colledge)

Within the Swan Coastal Plain, it is estimated that up to 90% of the endemic bushland has now been removed. While a considerable focus is made of endangered species of wildlife and on preservation of pristine bushland, it is clear that to retain of much of the original fauna and flora of this region, it will need preservation of all of the remnant vegetation possible. The Approved Conservation Advice for Honeymyrtle shrubland on limestone ridges of the Swan Coastal Plain Bioregion (15 Nov 2023) has clearly stated that retention of as many areas as possible of this scrubland is critical, even if it requires regeneration or is being rehabilitated, and that there should be no further clearance of this TEC. This is particularly so given less than 200 ha of this shrubland now remains.

The limestone country of the Swan Coastal Plain was known by the Whadjuk Noongar people as Booyeembara. It was and remains culturally significant. Prior to European habitation of Fremantle and adjacent areas, the Honeymyrtle shrubland is likely to have existed along a good portion of the Booyeembara from Manning Park in the south across Clontarf Hill, possibly Monument Hill, and most likely Booyeembara Park/Royal Fremantle Golf Course ridge areas and Cantonment Hill. It is possible it was also growing across the river at Cypress Hill, Buckland Hill and around the Mosman Park area.

Friends of Groups in many of these areas work tirelessly to rehabilitate the bushland of these areas in association with their respective local authorities. They remain committed to protecting remnant bushland, many times when there is little support from authorities. It is not too soon that the determination for this remnant bushland has been made. The task now will be to put in place appropriate preservation and rehabilitation plans for areas already identified with the Honeymyrtle scrubland and to investigate the others suspected of hosting remnants of this scrubland which is considered significant in patches of only 10m x 10m. It need not be pristine – rehabilitation is very much considered part of its preservation. Manning Park has one of the most extensive areas of this shrubland locally. It is also present in parts of Mosman Park. It will be worth exploring Clontarf Hill, the slopes of the limestone at Booyeembara Park, Cantonment Hill and areas on the north side of the river where there are limestone outcrops and may well be patches with some or several of the Honeymyrtle shrubland species as defined in the Approved Conservation Advice documentation (November 2023).

Key groups are Friends of Mosman Park Bushland, the North Fremantle Community Association, Friends of Cantonment Hill, Friends of Clontarf Hill, Friends of Booyeembara Park and Friends of Manning Park Ridge. Several are members of the Urban Bushland Council which is the collaborative body for some 120 Friends of groups across the metropolitan area, and all doing exceptional work to raise the profile and importance of these remnant patches of what was once extensive bushland habitat hosting many faunal species. Christine Richardson, representing the Urban Bushland Council and event organiser for the workshop, stated that “the detailed knowledge shared by the speakers at the workshop provided an invaluable understanding of the limestone ridge ecosystems and their values”. It will be hugely important to review the species present in all of the limestone ridge areas, to determine whether remnants of the Honeymytle shrubland can be locally identified and rehabilitated.

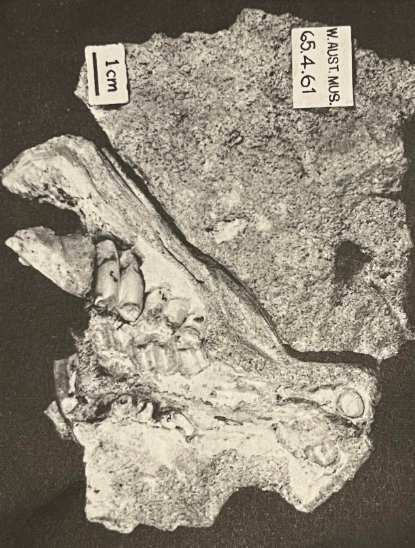

The wombat

And the wombat? Well, some 20,000-25,000 years ago a wombat wandered about in the dunes which then existed in the area of Mather Rd quarry in Beaconsfield. Its demise at that location meant some of its remains, part of the skull and lower jaws, were buried in the then dune sands and which later became accreted into the fossil dune system of the Tamala Limestone. While Messrs P Masilio, J Panizza, A and P Bartholomei and J Deane were quarrying limestone from the quarry in 1965, they found said wombat’s teeth protruding. On contacting the WA Museum, staff investigated and identified the fossilised remains as a Western species of bare-nosed wombat – as had also been found in fossil deposits in Mammoth Cave in the Tamala Limestone of the Margaret River region. Wombats have been locally extinct in this part of Western Australia for many thousands of years.

Just amazing what the Tamala Limestone delivers!

By Jenny Archibald in collaboration with the Friends of Booyeembara Park, Cantonment Hill, Clontarf Hill, Manning Park Ridge, Mosman Park and the North Fremantle Community Association, 15 May 2024

Acknowledgements. We are grateful to the following speakers who gave their time and expertise to the event held in March 2024 – Noongar knowledge holder Iva Haywood-Jackson, Dr Ken McNamara (Adjunct Professor), Adjunct Prof. Greg Keighery (also Chair of WA Threatened Species and Communities Scientific Committee), Emeritus Professor Hans Lambers, Emeritus Professor Will Stock, Professor Kingsley Dixon, Ms Cate Tauss (Independent consultant botanist) and PhD student Michael Just.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

* If you’d like to COMMENT on this or any of our stories, don’t hesitate to email our Editor.

** WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

*** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!