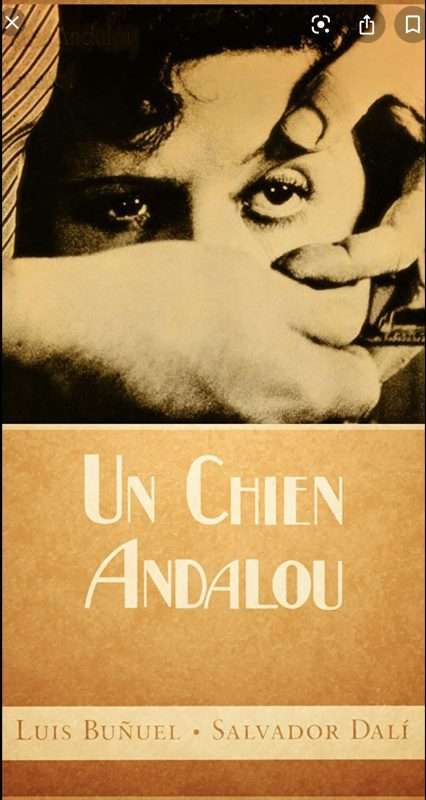

Artists have used whatever technology is available to them to extend their practice and make a living. During the Renaissance, Albrecht Dürer exploited etching and engraving techniques to make some of the most profound images ever created while making a tidy profit. In 1929 Salvador Dalí collaborated with Luis Buñuel to make one of the most notorious and provocative films of all time, using the relatively new technology of silent cinema. It opened for a limited season at Studio des Ursulines in Paris but was so popular it ran for eight months.

Making art is one thing, finding a market for it another, and this changes over time. Dürer marketing his own work, and Dalí and Buñuel found an audience through word of mouth. For the past two centuries, since the Salon des Refusés in Paris in 1863 when a young man saw potential to sell the work of artists like Claude Monet and Edouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, and others to the newly wealthy middle class, the art market has been the preserve of the private gallerist. Paul Durand-Ruel opened the first dealer gallery following the media frenzy generated by Manet’s work, and the model has remained with us into this century. But situations change, and as they do, artists need to find new platforms to reach an audience and to sell their work.

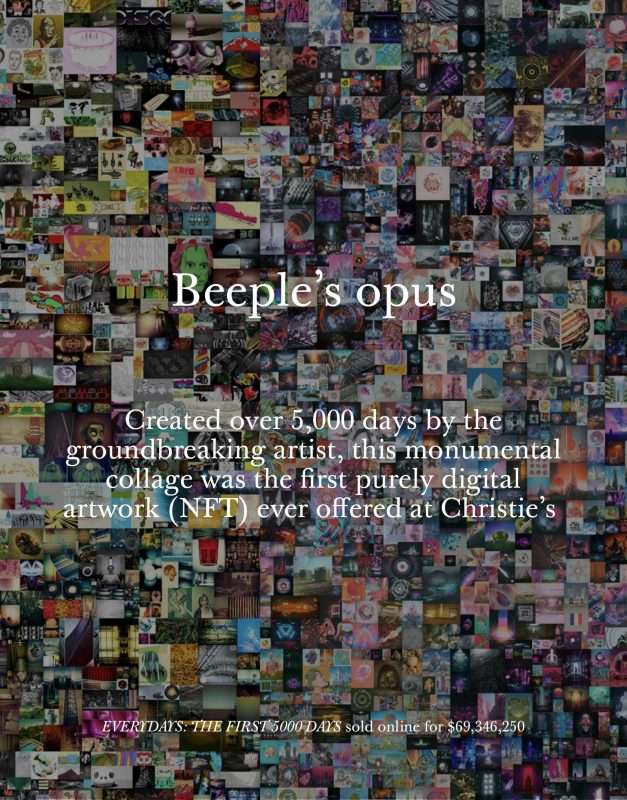

Non Fungible Tokens (NFT) are the latest platform, allowing artists to sell the license of their artwork to one individual. The data stored on a blockchain guarantees its ‘unique’ presence, though, of course, it can be reproduced endlessly. Using cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, it is possible to purchase this license, and the artist who sells it gets a royalty on each future sale. This is so much fairer than the traditional auction system that sees the original artist out of the loop after their initial sale. For the purchaser the item then acquire is a digital file, which they can print out, put on a screen or broadcast.

NFTs became big news recently when the American digital artist Beeple sold an NFT for $US69 million. Not surprisingly, people began to take note. In this case the work was a digital creation but the license purchased may or may not be the ‘original’ work itself. Some artists have reported the surprising fact that the artwork (painting, sculpture, installation, film music clip, whatever) they used to create the digital file is actually worth less than the NFT. Despite the shock horror of these sums being exchanged for a data file, it simply reinforces the need for artists to find an audience and make a living, however, they can.

For artists that are physically distant, this new platform offers some exciting options, and no doubt, many are already interrogating how to exploit this new technology to further their creative practice while simultaneously making money to support themselves. Based on those previous artists like Dürer, Dalí, and Buñuel, it is possible great art might be created along with the bites of rubbish that will inevitably flood the market place. Some artists will make money, which is a good thing. However, entrepreneurs like the Cock Foster brothers are already pushing their noses into the trough. Is it possible that this will be another case when the artists are forced aside and their work exploited, or can this new technology work for artists and provide a lucrative reward for their creative endeavour? Time will tell.

By Ted Snell @recommend_ted