Today, it seems, everyone has a view as to where the State’s gateway harbour near Fremantle should be. So, ‘Yes, it should stay where it is in the Inner Harbour’, or ‘No, it should be somewhere south, like Kwinana’, are common responses. And there are today many strands to the debate.

This is not a new debate, however. When you dig around a little, you discover we have been contending over the best Freo harbour location for most of the years since Lieutenant Governor James Stirling raised the Union Jack on Rous Head on 2 June 1829 and proclaimed Whadjuk Noongar territory henceforth to be a British Colony.

The first berthing places for vessels arriving at Freo, after it was established as the main port for the new Colony in 1829, were at various jetties adjacent to Arthur’s Head – near today’s Bathers Beach.

This was particularly because a very rocky bar across the entrance to the Derbarl Yerrigan – earlier given the name, Swan River, by the passing Dutch navigator Vlamingh – prevented most vessels of any size from entering the river. Unlike at Sydney Cove where Arthur Philip could sail into the harbour and up to where Circular Quay now is, sailing into the river and up to Perth was not an option in 1829. (Nor is it today.)

One would have few doubts, however, that the rocky bar was a significant creation of a mythical being during the Aboriginal Dreaming and was always of enormous religious significance to the Noongar Peoples. One suspects that if the idea of blasting out the rocky bar with gelignite, to make a new harbour beyond it, had been put to a Whadjuk Noongar vote at any time after 1829 and up to 1897, it would not have been seconded and certainly would not have got across the line.

However, plans for a safer and better, more efficient, harbour were advocated pretty much from the start of settlement with no regard to Noongar law or custom.

J S Rowe, the first Surveyor General who did the first town plans for Fremantle and Perth, produced, in 1839, what FWB Stevens, then Secretary of the Fremantle Harbour Trust, called, in his 1929 ‘The History of The Fremantle Harbour’, the ‘first authentic design’. Roe contemplated a harbour being constructed under the shelter of a breakwater off Arthur Head, ships to lie at moorings and their cargoes to be handled with lighters.

Rowe’s assistant surveyor, William Phelps, it seems was the first to propose opening the mouth of the Swan River, in 1856. His idea was to have a narrow channel leading from Gage Roads, the offshore channel, to the deeper reaches of the river. The thinking then was that vessels would find their way to Perth.

In those very early days the burden of the vessels in question was less than 300 tons and perhaps sailing on to Perth was vaguely possible. By contrast, today’s visiting container ships often have a tonnage of 60,000 or so, and cruise ships more like 70,000. As ships got bigger, the Perth destination was just a pipe dream.

Two reports on how to do a harbour were commissioned from Sir John Coode, an eminent British harbour authority. He produced them in 1877 and 1888. Like Rowe, he recommended outer harbours, away from the mouth of the Swan, protected by breakwaters.

Then C Y O’Connor entered on the scene, following his appointment, in 1891, as Engineer-in-Chief and General Manager of Railways of Western Australia. At the time of his appointment the Colony had just received, in 1890, responsible self-government from London. With revenue from the gold rushes beginning to fill the Colony’s coffers, the sky seemed the limit when it came to infrastructure proposals. CY had his own firm ideas on how to do harbours and other big infrastructure things.

Two options were then debated for the harbour. One, put forward by the then Colonial Government, was for a harbour in Owen Anchorage – where the Port Coogee marina has now been constructed – lying 3 miles south of Gage Roads. It was proposed to be reached by a channel through the Success Bank between Gage Roads and Owen Anchorage.

The other idea – CY’s idea – was to open the mouth of the river and create an inner harbour, which could be extended in later years, going up the river as demand arose from increased trade.

After much public debate, including a joint house inquiry in Parliament, CY’s idea was backed. Stevens’ History provides a blow by blow description of events.

Sir John Forrest was the Premier at the time. After initially supporting the Government option, he came round to supporting CY’s. Forrest also considered, as Stevens has recorded, that the inner harbour option might one day lead to ‘large ocean steamers, if perhaps not of the very largest class, going right up to Perth’.

However, the design then, as now, was limited by the existing nearby bridges across the Swan River, not to mention the depth and width of the river and the increasingly large vessels likely to arrive in Fremantle.

So, the Inner Harbour was then constructed, including by using gelignite to blast out the ancient rocky bar that, as observed, had prevented most vessels from entering the river mouth right through history. And the mouth was dredged to create the harbour we have today.

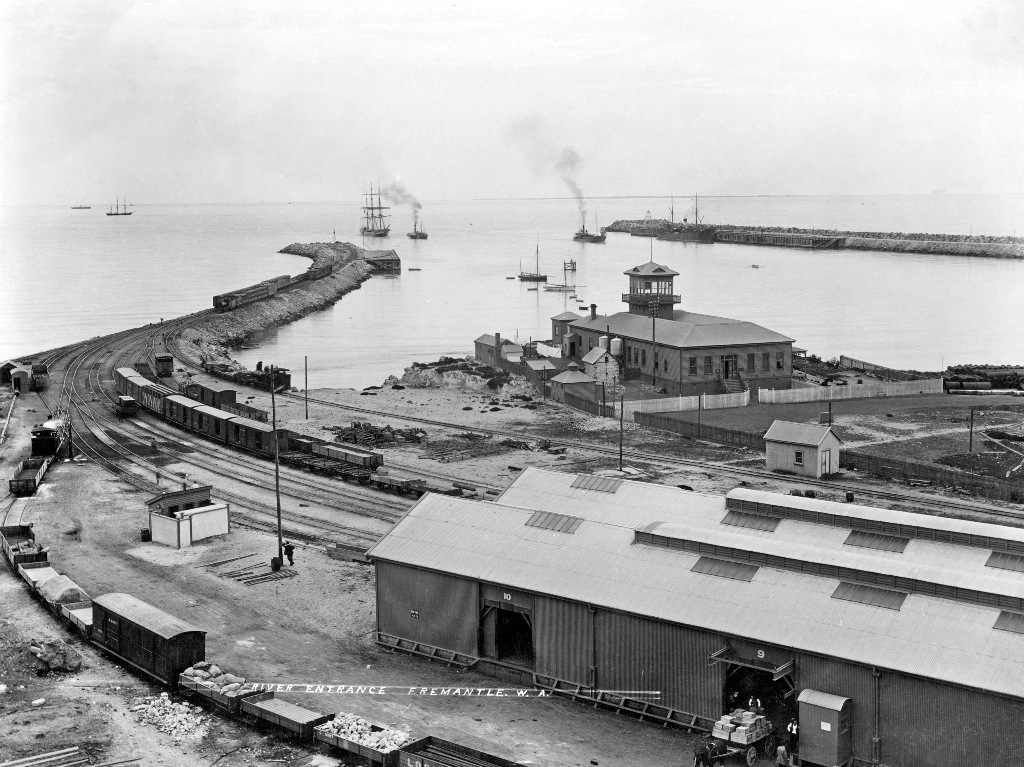

The Inner Harbour was officially opened on 4 May 1897, when the old steamer Sultan – which was a regular on the Singapore-Fremantle run, found her way into the new harbour through the gap that had been blasted in the rocky bar.

As Stevens has noted in his History, the alternative Owen Anchorage idea didn’t go to waste. It was later used as a place for disembarkation of live cattle and shipments of explosives. Many of us remember the abattoir at Robbs Jetty, long since gone along with its odours, now replaced by flash apartments and housing estates.

What many of us may not realise, however, is that soon after the Inner Harbour opened for business, in 1910, on the recommendation of British Admiral Henderson, the Federal Government decided to create a naval base on this, the Western side of our large island continent, and acquired Garden Island, as well as a strip of land near Woodman’s Point on Cockburn Sound, for the purpose. The influence of Sir John Forrest in all of this may be assumed, he being an influential politician in the first decade of the new Commonwealth. Works were actually commenced to carry this undertaking forward.

By 1921, however, after the First World War, the 7,000,000 pound – yes, 7m pound – project collapsed.

Nonetheless, the Garden Island acquisition remained intact, and today we have the naval base HMAS Stirling as our western naval protector. And as a reminder of those times, 100 years ago, just south of Woodman’s Point we have the camping site that still bears the locality name, Naval Base!

Stevens has suggested that the peace after the First World War, and environmental factors, ultimately put paid to the idea of using Cockburn Sound as a deep water harbour. As Stevens put it, ‘nature’ protected the beautiful body of water there from exploitation as a deep water harbour.

How times changed though, once the Second World War was over and Western Australia was anxious to reconstruct its economy in a new prosperous, peacetime, with lots of immigrants to run a new Kwinana industrial area.

The question of where a major harbour ideally should be located never quite went away, despite CY’s great endeavour. Between 1897 and 1929, the inner harbour facilities were significantly upgraded by the old Fremantle Harbour Trust. But even so, as of 1929, when he penned his History, Stevens noted that ‘the suggestion of building a new harbour in Gage Roads is showing its head, and is for the moment a matter of discussion’.

After World War Two, the regional planning ideas leading up to the promulgation of the 1963 Metropolitan Region Plan, envisaged something in the nature of a port happening in the general Kwinana vicinity, and of course it did with the creation of the Kwinana industrial precinct.

Various government studies into the 80s and beyond kept stirring the alternative harbour pot.

So, the question of the location of a major harbour in the vicinity of Fremantle capable of taking increasingly larger vessels and dealing with increasing trade, safely and efficiently, is not a new one.

Vessels are now a tad bigger than the 300 tons folk were talking about in the 1870s. C Y O’Connor understood they’d keep getting bigger and that there’d be more of them coming by as trade increased. He wasn’t wrong.

In 50 years time, as the latest report from the State Government agency Westport, referred to below, estimates, Fremantle Ports will need to handle cargo of about 3.8 million TEUs – Twenty-foot container Equivalent Units.

Today, container ships are regarded by their capacity to hold containers, naturally enough. The largest now being built, which can’t fit in the inner harbour, or indeed at any Australian Port, are now in excess of 20,000 TEUs. To give a comparison, these behemoths are said to have a capacity 16 to 17 times that of a pre-World War Two freighter. Have a look at these biggies.

As to where we should harbour vessels of these dimensions, or even the size of those big ones currently arriving at the Inner Harbour in the future, is a big question yet finally to be resolved.

The latest Westport report from August 2019, says the main harbour should preferably be a stand alone harbour at Kwinana.

The report considers that even with the construction of the contentious Roe 8 highway extension and other proposed infrastructure improvements, difficulties with road and rail access into Fremantle Port would remain too significant. The report states:

“The high cumulative capital costs, concerns over the long-term sustainability and scalability and large levels of social impact, meant that the two stand-alone Fremantle options … performed poorly,” the report stated.

The report also considered other benefits arose in moving the port from Fremantle, including fewer freight vehicles in the western suburbs and the ability to redevelop land at the existing facility for other uses.

The Government media statements on the Westport shortlist report also makes useful reading.

A new outer harbour designed to take major container ships would undoubtedly involve a de-scaling of Fremantle’s Inner Harbour.

There is anything but universal endorsement of Westport’s preference.

The Maritime Union of Australia has been and remains a critic, believing there is no pressing need for change. The MUA points to factors such as the depth of the port in Fremantle to accommodate larger ships, the reduction in road congestion in the past year, and the productivity improvements in the past year as reasons Fremantle could operate for about another 30 years.

Others point to environmental concerns in Cockburn Sound if the move is made.

In early 2020 we will host The Great Port Debate as a means of both better informing the public, especially Freo people, about the Westport preference and what is to be lost or gained by going down one channel versus another.

We are committed to an open, informed and respectful debate about the Port and its future.

If you or your organisation would like to contribute to the Debate, contact our editor, Michael Barker, here.

In the meantime, Fremantle Shipping News invites your letters to us, by email here, in support of the existing Fremantle Inner Harbour or for the Kwinana Outer Harbour preference.

Let The Great Port Debate begin!