The pandemic has begun to fade in our everyday consciousness. Covid variants have far from disappeared but ‘the virus’ is a background story – at least for most of us. While this may be cause for satisfaction and a lessening of individual anxieties, the same cannot be said for the impact of our changing climate and the myriad of factors affecting the health of our planet and the species that reside here. It’s taken a few decades but there is now widespread political and community acceptance that – yes, we do have a Problem. Not only that, we have a problem that already is an existential threat to human life and well-being; a threat that most certainly will manifest on a greater and more serious scale in the coming years.

Unless we disbelieve 97% of scientific opinion and have convinced ourselves climate change, so far as human input is concerned, is ‘unreal’ or a hoax perpetuated upon us, we are faced with a couple of key questions: What can be done about it? And, is it already too late?

Credit JenniferSumpton Photography

The first question implies a degree of hope. A firm (or tenuous) belief that, although greed and ignorance may have got us into this mess, human ingenuity is capable of reversing current trends. Within this optimistic approach, creative thinking and technological advances can hold global warming at bay, transition from fossil fuels to ‘clean’ energy, redress the pollution of our air and oceans, retain the permafrost of the northern hemisphere and the Arctic and Antarctic ice caps, reforest the Amazon basin, and restore habitat for wild species faced with extinction.

Much of the individual and collective impetus to ‘combat’ climate change and to move from fossil fuels to renewables is underpinned or buttressed by a honey-coated, fingers-crossed belief system. What we might term ‘the psychology of hope’ is seen as a counterforce to pessimism and inaction. Courtesy of the Fremantle Library, I am currently reading Jane Fonda’s inspiring book, What Can I Do? This energetic octogenarian decided she could no longer sit on the environmental sidelines and thrust herself into an activist role with ‘Friday Fire Drills’ – essentially public protests in Washington DC and elsewhere which inevitably lead to arrests – essential to attracting requisite media interest. Drawing from her experience as a protester during the Vietnam War, Fonda felt moved to participate rather than cheer from a comfortable Californian couch. Good luck to her, and those other committed people she mentions.

Alongside Fonda’s book, I have How To Avoid a Climate Disaster by Bill Gates. The co-founder of Microsoft gets a bad rap from the conspiracists who look under every bed for profit motive. I doubt whether many of them will read his book for they otherwise might be obliged to come up with something more nuanced. Gates asks the hard questions, is upfront about his own carbon footprint, yet remains confident there are ways and means to right the planetary ship. And, in Chapter 12, he adds practical advice about what ordinary folk can do – as citizens, consumers, employees or employers. Above all, he believes engagement in the political process ‘is the most important single step that people from every walk of life can take to help avoid a climate disaster’.

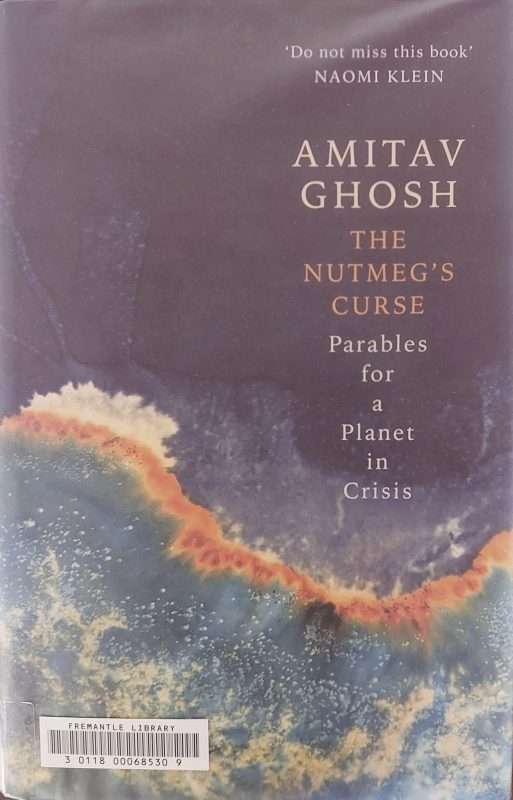

Other commentators are not so sanguine. Amitav Ghosh is better known for his novels. He was born in Calcutta and grew up in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and India, and now lives in New York. Our worthy library also unveiled The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis. Ghosh’s marvellous tale begins in the Banda archipelago – now part of Indonesia. During the early 17th century, the Dutch East India company, unwilling to share the fruits of the spice trade, acted as European colonial conquerors did elsewhere – treating indigenous inhabitants as sub-human, and wiping them out as best they could. Ghosh gives a historical perspective around how these attitudes were engrained in European thought and culture, and how their influence still affects the world we know today. The parables he outlines are designed to have privileged folk reflect upon their assumptions and biases. To take a contemporary example, the term ‘climate migration’ has become popular. Used to describe people fleeing from their homeland due to flooding, drought, and other climatically-relevant factors, it only captures a fraction of the story. For the migrants Ghosh interviews, ‘climate change was not a thing apart, a phenomenon that could be isolated from other aspects of their experience by a set of numbers or dates’. Beyond any analysis focussed upon extreme weather patterns, lurk ‘deeply entrenched structures of exploitation and conflict.’

The author looks through a relational lens: ‘Viewed from this perspective, climate change is but one aspect of a much broader planetary crisis: it is not the prime cause of dislocation, but rather a cognate phenomenon. In this sense, climate change, mass dislocations, pollution, environmental degradation, political breakdown, and the Covid-19 pandemic are all cognate effects of the ever-increasing acceleration of the last three decades. Not only are these crises interlinked – they are all deeply rooted in history, and they are all ultimately driven by the dynamics of global power.’

English academic, Jem Bendell, is equally sober about where we are at and how it has come about. For 25 years, Bendell was employed as a researcher, manager, and consultant to NGOs including the World Wildlife Fund, as well as United Nations agencies. As he acknowledges, his paid work reflected an overriding personal investment in environmental salvation. But he came to distrust both the proffered solutions, and the political and social systems within which these solutions are endorsed and promoted. In his view, the problems we face have been grossly understated. Not by all climate scientists but certainly by many who have long-established credentials, in particular, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the international body charged with assessing the science and providing guidance.

The subtitle of Bendell’s recent book, Breaking Together, is ‘a freedom-loving response to collapse’. These words are important. Bendell frames freedom as ‘the ability to think and act as we choose, without coercion or manipulation, and with meaningful awareness of our situation and the possible effects of our choices.’ It embodies a natural human desire that is also ‘natural to the living world’. As for ‘collapse’, this refers to the ongoing breakdown of modern societies, whether rich or poor. Bendell and his team examined data that show how people’s experiences and perceptions, as well as official indicators, reveal a significant decline in our level of well-being. This trend arose some years before Covid. In his 2018 paper, Deep Adaptation, Bendell defines societal collapse as ‘an uneven ending of industrial consumer modes of sustenance, shelter, health, security, pleasure, identity, and meaning.’ Collapse does not come as a sudden event but rather as a continuing process. Fundamental to what is ahead, according to Bendell, is a collapsed monetary system. As he points out, ‘a monetary system where private banks issue our money supply as debt cannot exist in an economy that does not enlarge itself.’ Never-ending growth and consumer behaviour, as other observers have remarked, underwrite modern economies. Bendell explains in depth how this approach cannot be sustained yet ‘fearing the negative impacts of economic recession, politicians are scared to do anything that would harm economic growth. That is why they are allied to growing GDP and won’t be swayed from that focus due to other considerations, like the environment.’

Bendell is at pains to acknowledge potential adverse psychological byproducts of his grim assessment. Humans cling to hope, and look to others – be they politicians or scientists or technological wizards – to problem-solve and deliver coherent positive messaging. Any stance that foreshadows impending and near-inevitable disaster is bound to cause distress. It also creates strong reactions from those who scoff at what they might label doomsday scenarios. Of this, Bendell is well aware. Though he self-describes as a ‘doomster’, he is no advocate of giving up and simply taking our medicine. He calls for ‘personal and collective changes that might help us to prepare for – and live with – a collapse of the societies we live within.’ There are four ‘R’ questions we can embrace. Resilience involves asking ourselves what we want to keep and how we might do so. Relinquishment addresses what we need to let go of, so as not to make things worse. Restoration involves looking at what we could bring back to help us. And with Reconciliation, we ask ourselves ‘with what and whom do we make peace as we awaken to our mutual mortality’.

Like Amitav Ghosh, Bendell has great respect for indigenous knowledge and insights, and the deep, abiding sense of interconnection that lies at the heart of indigenous cultures. He is at odds with the stance taken by some environmentalists who see the impact of humans as inherently damaging, and points to ‘mounting evidence of profound human influence in positively shaping biodiversity over millennial scales.’ At the same time, he is no romantic Pollyanna, advocating a return to some long-lost garden of Eden. But – and this recognition underscores ecological movements everywhere – we are invited to view a healthy natural environment, with species diversity, not simply as luxury escape from urban drabness but as a crucial aspect of human flourishing.

Having read this far, you may find an urge to distance yourself from what appears to be a fatalistic and perhaps flawed view of our collective future. As I sank into the narratives put forward by Ghosh and Bendell, I was also brushed by a sense of hopelessness. Wouldn’t it simply be better to ignore such weighty analyses of human folly and fate? After all, most of us are doing what we can to make sense of the life we are given, and to contribute in ways that give us meaning. And, as I read not so long ago, there are those who proclaim that ‘despair is not an option’. But the more I took in, the more it resonated, both rationally and intuitively. I would like to think otherwise – to cloak myself in optimism and maintain a message of hope. Yet, it feels more honest to pay close attention to Bendell’s work, and to reassess where I stand. It resonates when he talks about facing up to what is actually happening, no matter how painful this might be. Perhaps gently shirtfronting ourselves might bring about some kind of dark night of the soul but that, in turn, carries possibilities of greater understanding and informed action. In Bendell’s words ‘despair is not a luxury, it is more of a laxative for purging our bullshit. There is a place beyond despair where we can begin again but, trying to avoid despair, people often don’t allow themselves to reach it.’

What makes us tick, especially in our responses or reactions to stress and conflict, has long been integral to my journey. Many people, I find, are incurious or find it hard to articulate what they are feeling, let alone attribute value to any kind of inner work or self-reflection. Maybe it’s partly an age thing, as younger folk can be more open (and, within the school system, kids may be lucky enough to get guidance about what is behind their impulses and motivations). For my age bracket, it is salutary to see how entrenched our worldviews can become, often reaching heightened states of inflexibility as the years roll on. This makes it difficult to engage in conversations and ideas that fall outside our zones of interest, or don’t rate in terms of priority, or about which we have already formed solid opinions. Most of my efforts to introduce friends to Bendell’s work have fallen flat. And I’ve even had dismissive comments from some in the environmental industry, along the lines of ‘it’s all old hat’. That attitude puts a full stop to any useful discourse.

It’s tempting to wallow in wishful thinking about influencing others. But that’s neither helpful nor healthy. Better to pop the red pill of self-awareness, attune to the soulful depths of despair, and trust the laxative will do its thing.

Right now, hope has taken a back seat. Perhaps there might have been a trigger warning before I painted this far-from-idyllic picture on a sun-kissed morning in my Fremantle cocoon. But I trust in the good sense and resilience of readers to make their own judgements on the current state of play. If the books I have mentioned, and my two bobs’ worth, assist that process, expressing these sentiments has been worthwhile.

* Based in Fremantle, most of the time, Bruce Menzies is the author of three novels, a family history, and a recent memoir. Details at BruceJamesMenzies.com If you’d like to read more of Bruce Menzies’ work on Fremantle Shipping News or listen to a fascinating podcast interview with Bruce, look here

WHILE YOU’RE HERE –

PLEASE HELP US TO GROW FREMANTLE SHIPPING NEWS

FSN is a reader-supported, volunteer-assisted online magazine all about Fremantle. Thanks for helping to keep FSN keeping on!

** Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to receive your free copy of The Weekly Edition of the Shipping News each Friday!