Shipping News readers have the opportunity to journey with the Hougoumont, the last convict ship to Australia which arrived in Fremantle on 10 January 1868.

On board were 62 Irish Fenian political prisoners as part of a total of 280 convicts. The 150 year anniversary of this event will be commemorated from 5 – 14 January 2018 at the Fenians Fremantle and Freedom Festival. There will also be an Exhibition of Transportation at the Fremantle Prison from 9 January 2018.

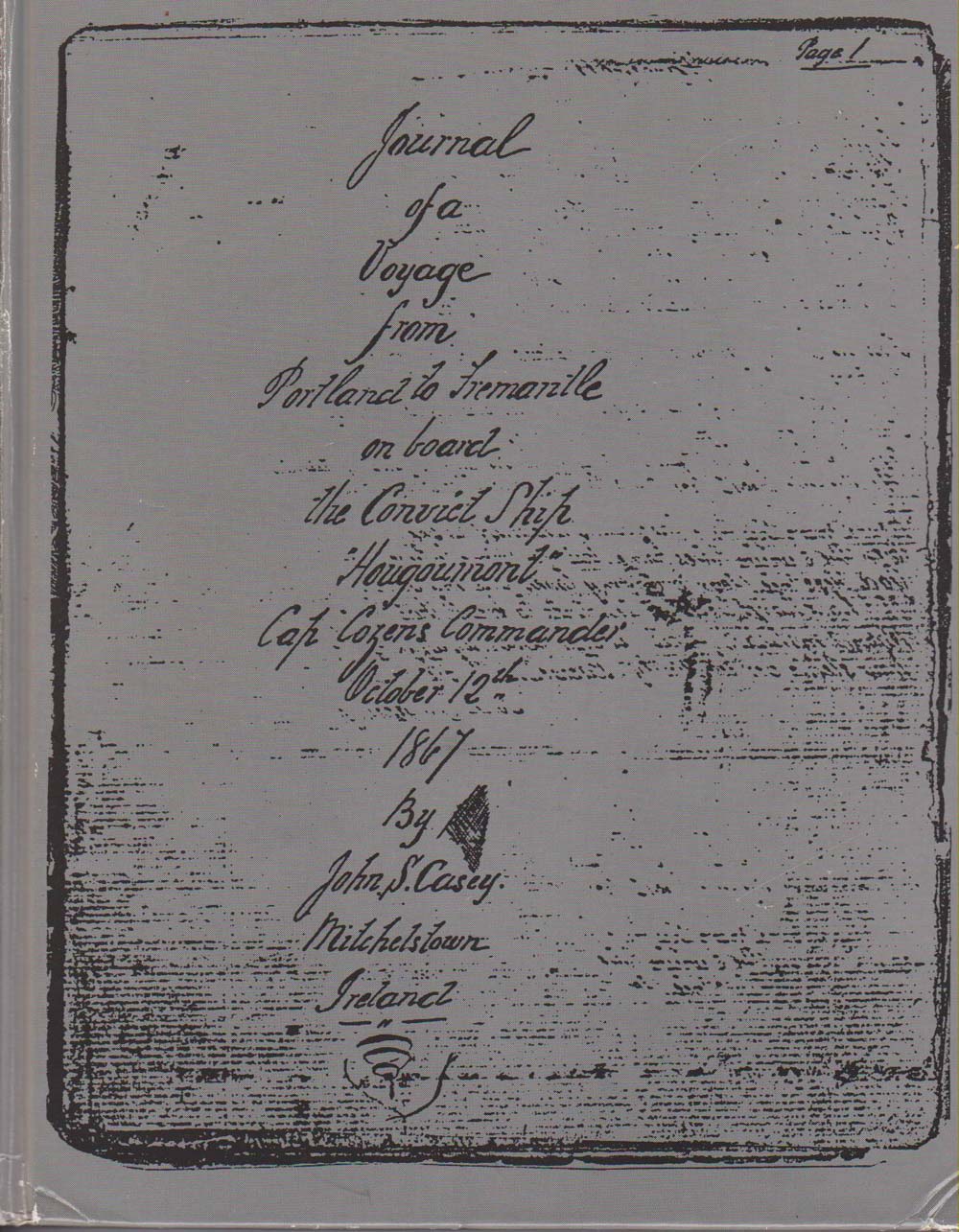

FSN readers who have been following these logs from the Hougoumont, are in for a treat. The Fenians Fremantle and Freedom Festival are happy to announce that one of our committee members, Donough O’Donovan uncovered an absolute treasure in a Perth second-hand bookshop – a reproduction of the on-board diary of the Fenian, John Sarsfield Casey.

I know many of you are now ‘hooked’ into this story, so let me share the journal with you…

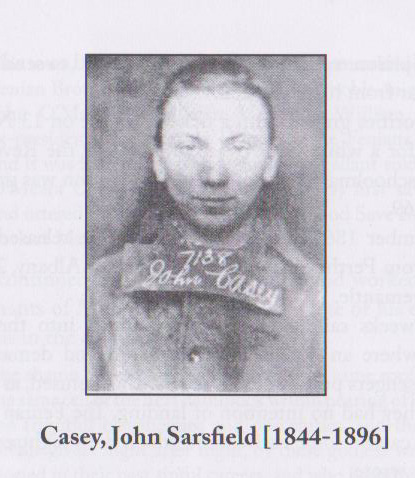

John Sarsfield Casey was born in Mitchelstown Co Cork in 1844, surrounded by the Galtee Mountains. His father, Jeremiah Casey was a shopkeeper and publican. As a town-dweller he was very aware of the extreme poverty of small farmers in the area and wrote that ‘the shadow of the famine had been visible in my childhood’.

The young Casey served as an alter boy and catechism teacher but also became deeply immersed in local historical traditions and in the nationalist press and popular literature. While studying at the local Christian Brother’s school, Casey involved himself in the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). He wrote letters to newspapers describing the history and traditions of the ‘Galtees’ where he contrasted the luxurious lives of the local landlords with the poverty of their tenants. This led first to his expulsion from school, then his dismissal from employment. His apprenticeship to a local draper was also short lived, after he quarrelled with a priest about his distribution of the Fenian newspaper, The Irish People. His letters to the local paper were published under his pen name, The Galtee Boy.

He was arrested at the age of 19 and found guilty largely for the sentiment expressed in these letters, which were presented as evidence at his trial. Casey’s prison diaries (published by University College, Dublin, Press) provide one of the most vivid descriptions of life in both English and Australian Prisons. By the time he boarded the Hougoumont, Casey had spent two years in cruel and inhumane conditions in Portland prison.

DIARY ENTRIES – JOHN SARSFIELD CASEY

Describing the routine on board…

6 o’clock – On deck and wash. Stay on the promenade deck.

8 o’clock – Breakfast – Biscuits and 1 pint of tea or chocolate on alternate mornings.

9 o’clock – Morning Prayers – on deck till 12 o’clock.

Dinner – in part fresh meat and tea; beef or pork – ½ pound with bone on alternate days with an ounce of flour and raisins.

One ounce of preserved potatoes and a pint of insipid pea soup with pork.

Supper – 1 pint of thin gruel – 2 ounces of wine.

11 o’clock – ½ pint of Lime Juice – very palatable.

Unfortunately for Casey he suffered more than anyone else on board from sea sickness. Most of his entries make reference to it, as does Cashman in his diary and other writers in the Wild Goose.

Exceedingly sick – get some ease by lying in bunk. None sick but myself. ‘Spued’ off everything I eat.

Exceedingly sick today – cannot drink that chocolate – cannot eat – stretched in a bunk all day, ship rolling. Bradley says that plum duff is a cure for sea sickness – intolerable thirst – Dr says he can’t cure seasickness.

October 15

Blowing hard – tacking very often – Sea boiling and dashing in over bulwarks – One sail to west – water not drinkable, soft warm and muddy – still sick – cannot retain anything in my stomach.

The following entry gives us some insight into the anxiety surrounding the presence of the Fenians on board the Hougoumont and the fear of an attempted rescue at sea of these political prisoners.

Around this time, Casey started adding Latitude, Longitude and the distance travelled into his diary.

October 18 Lat: 48 2’North Lon: 6 6’ West Miles 63

2 o’clock – sail ho – a Fenian cruiser? All hands rushed on deck and in an instant bulwarks an forecastle are crowded with anxious faces chatting and pointing in direction of supposed cruiser who is baring down on us – she hoists no colours when within ½ mile of us. Dreadful excitement prevails on deck. Captain and Surgeon examining her with a glass – She is so close now to us that faces can be distinguished on her deck – she is still ‘incognito’. In a few minutes, a faint cheer is heard from her and scarcely has it died away ere a deafening cheer bursts from all hands who expect that the hour of deliverance has, at length arrived. Alas, another minute and the Union Jack is proudly waving to the breeze and the ‘Fenian cruiser’ turns out to be an English merchantman bound to Liverpool with a cargo of rice.

October 20: Lat: 45 16’North Lon: 7 9’ West Miles 116

Very sick – eat no breakfast – scarcely able to crawl. Sea quiet calm. Sail to the S.E. showing English colours. A huge monster (whale) dashing up spray – shoals of porpoises gambolling.

9 o’clock, land to the south east, faintly visible in the haze – Spain. Though scarcely able to crawl, I mount upon the forecastle and gaze upon that romantic land. It appears to consist of cold hills, ‘sierras’ extending in unbroken succession along the coast – Too far from it to distinguish anything further.

11 o’clock – On deck again. The vessel seems scarcely to move as she cuts her way through the water – the misty outline of the coast becoming gradually more visible and at length the blue mountains could be seen as the day wore on. Their wavy outlines sharp and well defined against the clear blue sky – remind me of sublime Galtee Mountains. I gaze with admiration at that romantic land and call to mind with pride the time when she was the scourge of England. Spain, how glorious are they mountains lakes rivers and sea coast!

On 15 November, the Hougoumont crossed the equator. We can only imagine the stifling heat and difficult conditions for fair skinned people, who had never been into climates like this before.

November 16 Lat: 0 12’ North Lon: 30 20’ West Miles 87

4 o’clock on deck. Moon on wane. All northern constellations have completely disappeared. Grand appearance of the ocean when illuminated by silvery light of the moon. Morning cool – strong breeze. Polar star has disappeared –day very warm – Sail in sight – proves to be a mail steamer from Melbourne to England, double funnelled, paddles etc.

12 o’clock – Sun very warm. Sky deep blue. The most magnificent clouds I ever beheld flitting across the surface.

November 22: Lat 17 26’ South Lon 30 14’ West Miles 117

Moring cloudy – have a severe cold in the head and throat and scarcely able to swallow a morsel or articulate a word. Eat no breakfast.

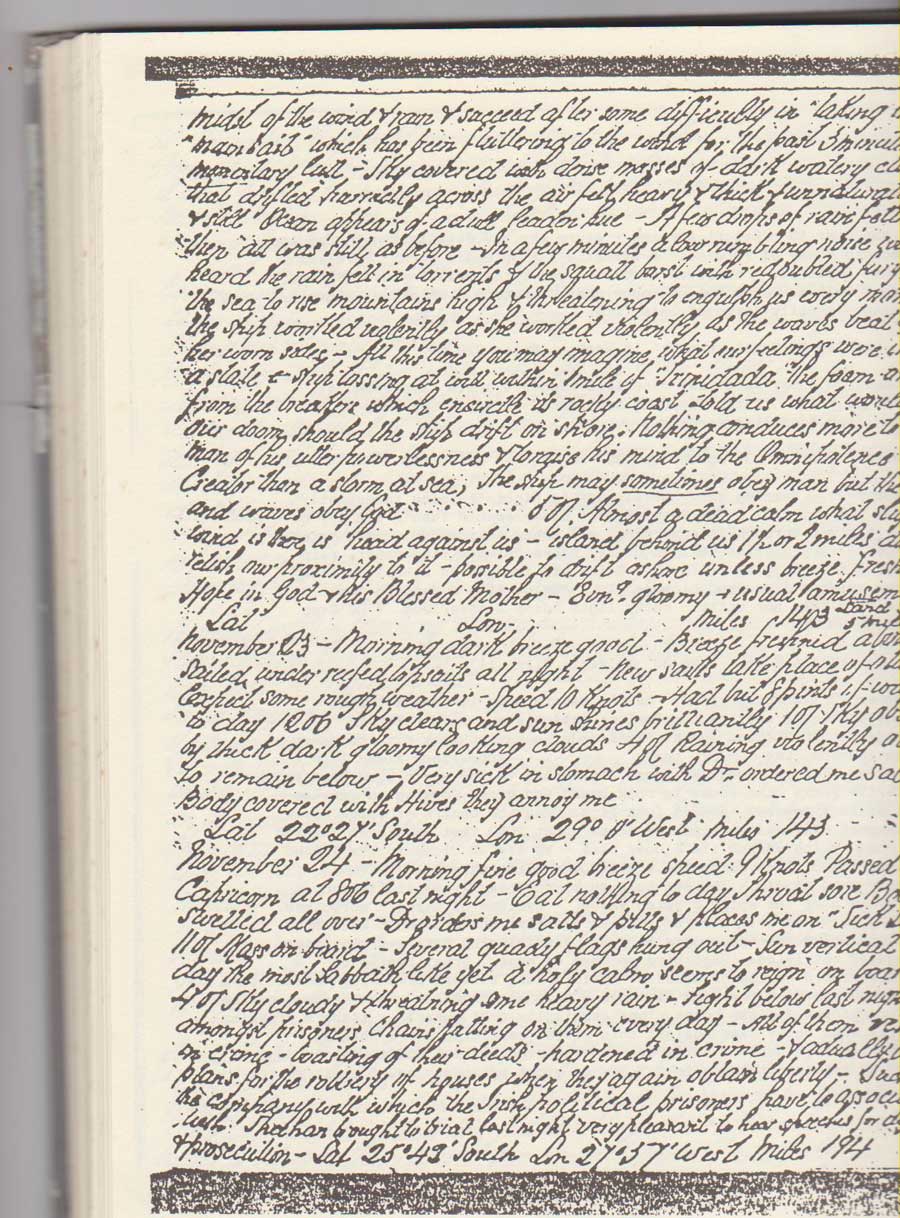

10 o’clock – Land ahead – ‘Trinidada’ a barren rock off the coast of South America. Rises from the ocean with an irregular front and presents to the eye rugged precipices and sterile rocks…forming an immense wall of rock several hundred feet high from the centre of which rises an immense cylindrical block of stone about 2000 feet high. We are so close to the island that we can discern cormorant and other sea birds perched moodily upon cliffs. Raining very heavily – have an idea of tropical showers – ship rolling- sea very heavy – change course to S.E. Wind blowing from every quarter – a regular whirlwind. Great bustle on deck. Expect a series of squalls – sailors hard at work preparing to meet them. Squall bursts with terrific violence – ship unmanageable – tossed about on the surface of the furious ocean – sea dashing over the gunwale – timbers creaking – several huge waves dash against the ship almost capsizing her and shaking every timber in her. Two sails are rent to ribbons – not sufficient hands on board to set everything aright. Six or eight prisoners mount aloft in the midst of the wind and rain and succeed after some difficulty in ‘taking in’ the mainsail. A momentary lull.

In a few moments a low rumbling noise was heard. The rain fell in torrents and the squall burst with redoubled fury causing the sea to rise mountains high and threatening to engulf us every moment. The ship worked violently as the waves beat against her worn sides. All this time you can imagine what our feelings were in such a state – ship tossing at will within a mile of ‘Trinidada’. The foam arising from the breakers which encircled its rocky coast told us what would be our doom should the ship drift on shore.

Nothing conduces more to remind man of his utter powerlessness and to raise his mind to the Omnipotence of his Creator than a storm at sea!

What happened to Casey after the voyage?

In November 1868 he obtained his ticket of leave and found work teaching in a school run by Fr Patrick Gibney in York. Casey won praise for his teaching skills and was offered advancement if he stayed in the colony, but he detested the frontier society and longed for Ireland. Despite the conditions of his ticket of leave, he participated in a network of local residents assisting those Fenians who remained working on the roads. In May 1869 he was one of the beneficiaries of a partial amnesty and left the colony in September of that year; their travelling expenses having been raised by supporters in Australia and in Ireland. He sailed on the Suffolk from Melbourne and arrived home in Mitchelstown in March 1870. He continued to write and involve himself in the cause of Home Rule for Ireland and the local land league as well as continuing to campaign for the release of the military Fenians from Fremantle. He died in Mitchelstown in 1896.